Article

Frankie Yale was a Brooklyn gangster and businessman with ties to Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria and Al Capone. His 1928 assassination coincided with dramatic changes in the Brooklyn underworld and the Mafia of the United States.

Yale apparently was born Jan. 22, 1893, in Longobucco, a town in the southern mainland Italian region of Calabria.[1] The original spelling of his surname was probably "Ioele."[2] His father, Domenick Ioele, was born about 1860. Census records indicate the birth year of his mother, Isabella DeSimone Ioele, was between 1863 and 1865.[3]

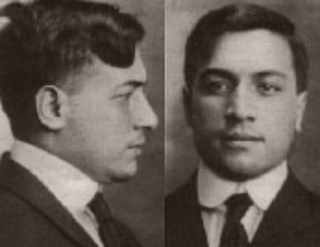

Frankie Yale

The couple's first son, John, was born in Longobucco about 1891-92.[4] Frank's birth and the birth of a sister, Assunta, quickly followed, and two years later another brother, Angelo, was born.[5]

Domenick Ioele crossed the Atlantic in 1898. His older sons are believed to have joined him in New York in the early 1900s. Isabella, Assunta, age 13, and Angelo, age 10, reached New York aboard the S.S. Nord America on Sept. 4, 1907. They originally were headed to meet Domenick at 46 Baxter Street, but were detained until the following day. They were then discharged to Domenico, whose address was revised as 65 James Street.[6]

By 1910, the Ioele family - including John and Frank, had relocated to 1440 66th Street in Brooklyn. Domenick was working as a wholesale produce merchant. John was employed as a postcard printer. Frank "Yale" was a railroad guard.[7]

Yale's first arrest occurred in October 1912. He was convicted of disorderly conduct and fined $10.[8]

In July 1913, he, Michael Petro and Andrew Bombara were arrested for first-degree robbery and second-degree assault. The victim, dry goods store owner Alexander Maporazzo initially recognized and identified Yale and Bombara as the young men who attacked him. Later in court, Maporazza changed his story. He was sure he was mistaken about the identities of his assailants. Magistrate Geismar ordered Maporazzo charged with perjury and held on $2,000 bail. The robbery and assault charges appear not to have been prosecuted, but the remained on the court calendars until at least the summer of 1914.[9]

Bath Beach, Brooklyn, Police entered a coffeehouse at 6408 New Utrecht Ave. on Feb. 1, 1917, apparently in response to a brawl. Two local men were arrested on charges of disorderly conduct. Yale, then 23, and two other men were arrested for carrying revolvers. The three armed men were held for examination in the Coney Island Court. On May 21, County Judge Fawcett convicted Frank Yale on the weapons charge and sent him to the penitentiary on Blackwell's Island.[10]

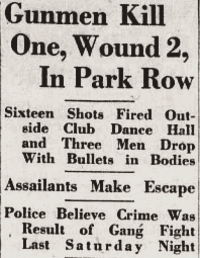

New York Tribune

Feb. 7, 1921, p. 3

Also in 1917, Yale took a bride, Mary DeLapere.[11] In June the following year, a daughter was born to the couple. They named her Isabella. Another daughter, Rose, was born in October of 1919. In January, 1920, the young Yale family was residing with Mary's parents in a multi-family home at 6605 14th Avenue in Brooklyn.[12] While becoming a major force in the Brooklyn underworld, Frank Yale reported that he was employed as an undertaker.[13]

Yale was noted in Chicago at the time of "Big Jim" Colosimo's May 1920 murder. Police considered him a suspect in the murder, until a witness, Joe Gabreala, abruptly changed his story. It is widely believed that rising Chicago crime boss Johnny Torrio, an old friend of Yale's from his Brooklyn days, called Yale to the Windy City to eliminate Colosimo.[14]

Back in New York, Yale was involved in a serious gang brawl on Manhattan's Park Row during the first weekend of February 1921. Yale and his allies were victorious in a free-for-all fistfight late Saturday night, Feb. 5. The fight continued Sunday night, as the defeated gang returned to the scene and opened fire with handguns immediately upon seeing their adversaries emerge from a hallway at 158 Park Row. Michael Demosci, 26, of Pearl Street, was shot in the head and killed. A bullet struck Yale in the chest. He was taken to Broad Street Hospital, where doctors determined that his wound was not life-threatening. Another companion, George Bellitti, 28, of Baxter Street, suffered a superficial wound to the head and was locked up at Elizabeth Street Police Station.[15]

Violence became a regular part of Yale's existence. Early in July 1921 he was arrested for involvement in the decapitation murder of Ernesto Melchiorre at Coney Island. Yale was quickly released for lack of evidence.[16] A short time later, on July 15, Yale's car was riddled with heavy-caliber bullets fired from a passing vehicle. Robert (Rocco) Lawrence of 72nd Street and Yale's brother Angelo were wounded in the attack. They were treated at Coney Island Hospital. Frank Yale and companions Anthony Carfano of 649 Union Street and "Babe" Cannalle of 13th Avenue were unharmed. The group was returning from an evening at Coney Island, where Yale owned a nightclub.[17] Carfano, also known as Little Augie Pisano, was Yale's top lieutenant.

Frank Yale

The brief Yale-Melchiorre feud was apparently ended eight days later with the daylight slaying of Silvio Melchiorre, brother of the recently murdered Ernesto. Silvio Melchiorre, owner of a cafe at Kenmare and Elizabeth Streets in Manhattan, emerged from his business that afternoon to supervise the weighing of a load of ice he had ordered. A stranger approached and entered into an argument with the cafe owner. As the argument continued, two men walked up, drew firearms and shot Melchiorre to death. Police quickly connected the recent events and took Frank Yale into custody. Yale was subsequently released for lack of evidence.[18]

Early in 1922, Yale was arrested and charged with violation of the Sullivan Law, which prohibited carrying a firearm. The arrest occurred despite the fact that Yale produced a pistol permit signed by Justice Strong of the New York Supreme Court. Yale was held at Raymond Street Jail in Brooklyn while the matter was argued in the courts.

The district attorney stated that, within the New York City limits, only the Police Commissioner had the authority to issue pistol permits. Yale's permit was not obtained through the Police Commissioner. On March 2, Supreme Court Justice Gannon ruled that Supreme Court Justices had the power to issue pistol permits valid within the city. Gannon ordered Yale released from the jail. At that time, the local press noted that Yale was owner of a funeral home business in Bath Beach and part-owner of a restaurant at 101 Flatbush Avenue.[19]

During 1922, Giuseppe Masseria eliminated a bothersome rival in Manhattan and became the borough's most powerful Mafia boss. Masseria soon incorporated Yale and Carfano into his growing underworld empire.[20]

Frank Yale cigars

Yale moved into a number of other businesses, including laundries, a taxi company and a cigar manufacturing plant, which produced "Frankie Yale" smokes with the crime boss's image on the box.[21]

He became popular in Brooklyn by sharing a bit of his wealth. Just before Christmas 1922, Yale distributed about 12 tons of coal to help heat the homes of the poort. One of the distribution spots for the coal was St. Rosalia's Roman Catholic Church, 63rd Street and 14th Avenue, in Brooklyn. [22] Yale repeatedly provided generous donations to St. Rosalia's.

Yet, the violent side of Yale's life continued. In the early morning hours of July 9, 1923, another attempt was made to murder him. The Yale family attended a christening party on the evening of July 8 and were just returning home at 1 a.m. A car drove up to the Yale residence at 6605 15th Avenue. The gangster's wife and daughters emerged and went into the house. As the vehicle pulled away from the curb and began to turn around, a touring car pulled up and shots were fired. The touring car sped away, leaving driver Frank Forte, 25, of 1305 65th Street, dead. Police and press concluded that Forte was killed by accident, as the gunmen had no way to know that Yale had decided to walk home from the christening party with Matteo Romano of 67th Street and had instructed Forte to drive his family home.[23]

Yale and "Sam" Pollaccia, 1924

Yale made another trip west to Chicago in November 1924, following the death of highly regarded Chicago Mafia leader Michele Merlo. Yale traveled along with Brooklyn Mafioso Saverio "Sam" Pollaccia. The visit of the Brooklyn mobsters coincided with the Nov. 10 murder of Chicago's North Side Gang boss, Dean O'Banion.

Chicago Police recalled that Yale had been in town when Colosimo was killed and suspected him of involvement in the O'Banion murder. Yale and Pollaccia were held, as police checked into their alibis. When their stories checked out, they were released.[24] The rivalry between O'Banion's gang and the Torrio-Capone gang in Chicago had recently heated up. Rumors indicated that Torrio had once again called Yale in from Brooklyn to fix a problem situation.

Yale's father, Domenico, died at his Brooklyn home on March 3, 1926.[25] His March 6 funeral was said to be among the largest recalled in Brooklyn. More than 35 automobiles filled with flowers and 266 automobiles of mourners participated in the cortege. It was a surprising display for a former produce merchant at Brooklyn's Wallabout Market. Immediately, members of the community formed a committee to accumulate funds and create a lasting memorial to the deceased. When Frank Yale learned of the project, he asked that the committee be disbanded and pledged that he would erect a monument of imported marble over his father's grave.[26]

That summer, Yale and his wife separated. Yale began spending time with a woman in Manhattan, though he continued to support Mary and their daughters.[27] He quietly sought a divorce.

Yale at groundbreaking

St. Rosalia's Church benefited in May 1927 from a series of boxing matches organized by Yale at the New Broadway Arena in Brooklyn. A newspaper account of the matches referred to Yale as a "popular Brooklyn sportsman."[28]

That summer, Yale married again. He and his wife Lucita were joined in a civil ceremony in Brooklyn. Some said that Lucita had formerly been married to a Mott Street restaurateur who was murdered.[29]

Authorities paid special attention to another Yale visit to Chicago in September 1927. Breaking with the earlier pattern, no top gang boss was killed during that visit. Yale reportedly went to the Windy City merely to attend the Dempsey-Tunney fight as a guest of his friend Al Capone.[30]

Capone had assumed control of Torrio's gang following Torrio's recent retirement. When friction began between Capone and Sicilian Mafia bosses in Chicago, Giuseppe Masseria stepped in to make Capone his personal vassal, a capodecina in the growing Masseria organization.[31] At about the same time, Masseria became quite close to Yale lieutenant Carfano.[32] Yale, targeted by rivals for many years, was growing less important to his primary underworld protector, Masseria.

Capone and Yale reportedly partnered in a rum-running operation. Rumors got back to Capone that Yale was cheating on his end of the operation. Capone responded by having a spy named James DeAmato inserted into Yale's organization. In July 1927, DeAmato was found dead on a Brooklyn street. He had been shot several times in the head.[33] The friendship between Yale and Capone ended at that moment.

On May 2, 1928, a daughter was born to Frank and Lucita Yale. About two weeks later, Yale was a visible participant in the groundbreaking for St. Rosalia's planned parochial school. The school was expected to cost $175,000.[34]

The following month, New York Supreme Court Justice Druhan granted Mary Yale an interlocutory divorce decree including alimony of $35 a week.[35] In the middle of that month, Capone left Chicago and traveled to his $65,000 villa at Palm Island, Florida. His movements were closely watched by the authorities.[36]

At about 4 p.m. on July 1, 1928, Yale was driving his Lincoln automobile along 44th Street in Brooklyn, when he was overtaken by a black sedan. Shots were fired into the Lincoln's rear window, and Yale accelerated in an effort to escape. The two cars came abreast between 9th and 10th Avenues, and a volley was fired by pistols and a sawed-off shotgun into Yale's car.

Yale's skull was crushed by the slugs, and his car veered off the road, crashing into the stone steps in front of 923 44th Street. He died immediately.[37]

Yale was given an elaborate gangland sendoff, arranged by the Graziano & Janone Funeral Home and his lieutenant Anthony Carfano.[38]

A funeral Mass was celebrated at St. Rosalia's Church, with the church's pastor, Monsignor A.R. Cioffi presiding. An estimated 15,000 people turned out to catch a glimpse of Yale's reported silver coffin, believed to be worth $15,000. The funeral cortege included 200 automobiles of mourners and a "mountain of floral tributes, gaudy enough to have satisfied even the show-loving gang leader." Despite the showy funeral, two years after Yale's death, his estate was officially valued at just $3,000.[39]

The police investigation of Yale's killing pointed to Capone. Three of Capone's associates reportedly had left him in Miami and headed north on a train that reached New York City hours before the murder. Investigators learned that Capone had threatened Yale following the slaying of James DeAmato.[40] Later, some ballistic evidence linked the weapons used in the Yale killing with those used in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre.[41]

Scene of Yale murder (Police removed Yale's body from the car).

Police arrested various individuals in connection with the Yale murder but were unable to assemble a convincing case against any of them. Giuseppe "Clutch Hand" Peraino and Giuseppe Florina (associate of Albert Anastasia) were both taken into custody early in the investigation but quickly released.[42]

Though the loss of his powerful Brooklyn group leader should have negatively impacted Giuseppe Masseria, Masseria appears to have suffered no ill effect. By the end of the year, Masseria was proclaimed boss of bosses of the Mafia in the United States.[43] Two other men appear to have benefited greatly from the elimination of Yale. Anthony Carfano took charge of many of Yale's lucrative rackets.[44] And Giuseppe Profaci, who quietly led a small Mafia organization comprised of relatives and fellow immigrants from Villabate, Sicily, assumed control of Yale men and territory in southern Brooklyn. The added strength and prestige instantly made Profaci a significant player in the national Mafia network.[45]

Notes

- This information is drawn from a World War I draft registration card for Frank Uale of 14th Avenue in Brooklyn. At the time the card was completed, June 1917, Uale was an inmate in the penitentiary on Blackwell's Island in New York.

- The Italian "Ioele" and American-English "Yale" are similarly pronounced. A number of sources identify the gangster as "Uale," a name that would be pronounced closer to the American-English word "whale."

- U.S. Census of 1910, Brooklyn borough, New York, Supervisor's District 2, Enumeration District 1073, Ward 30; U.S. Census of 1920, Brooklyn borough, New York, Supervisor's District 3, Enumeration District 955, Ward AD-16; U.S. Census of 1930, Brooklyn borough, New York, Supervisor's District 32, Enumeration District 23-1389, Ward AD-16; Domenico Ioele Death Certificate, No. 5158, Kings County, NY, March 3, 1926.

- A probably incorrect birthdate of June 13, 1892, was provided by John Ioele on his World War I draft registration. Problems with the date include the birth of brother Frank less than seven months later and John's reported age of 18 at the time of the 1910 U.S. Census. 1891 appears to be a more likely year of birth.

- Angelo Ioele World War I draft registration, Brooklyn, NY. Angelo, like his brother Frank, pursued a life of crime. For years after Frank Yale's death, Angelo continued to get in trouble with the law.

- Passenger manifest of S.S. Nord America, departed Naples on Aug. 22, 1907, arrived New York City on Sept. 4, 1907.

- U.S. Census of 1910.

- "Gangster shot dead in daylight attack," New York Times, July 2, 1928, p. 1.

- "List of those who entered not guilty pleas a long one," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 31, 1913, p. 16; "Hold merchant for perjury," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 9, 1913, p. 2; "Brooklyn courts," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 21, 1913, p. 3; "The courts," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov. 4, 1913, p. 14; "Brooklyn courts," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 7, 1914, p. 12.

- "Say three carried guns," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 2, 1917, p. 20; "Prison, then exile for daring robber," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 21, 1917, p. 3. Yale registered for the World War I draft on June 2, 1917, while an inmate at Blackwell's Island.

- The marriage appears to have occurred before he was sentenced to prison. Mary's surname has been written as "DeLapere" and "Delepia."

- U.S. Census of 1920.

- U.S. Census of 1920.

- Pasley, Fred D., Al Capone: The Biography of a Self-Made Man, Garden City NY: Garden City Publishing Company, 1930, p. 239; Thompson, Craig, and Allen Raymond, Gang Rule in New York: The Story of a Lawless Era, New York: Dial Press, 1940, p. 101.

- "Gunmen kill one, wound 2, in Park Row," New York Tribune, Feb. 7, 1921, p. 3; Thompson and Raymond, p. 101. Thompson and Raymond place Yale's shooting injury in 1920, but it seems certain they were referring to the February 1921 brawl.

- "2 men wounded when gangsters attack in motor," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 15, 1921, p. 18; "Gunmen kill man in crowded street; old feud suspected," New York Tribune, July 24, 1921, p. 7.

- "2 men wounded when gangsters attack in motor;" "Auto gunmen wound two in car and flee," New York Tribune, July 16, 1921, p. 13.

- "Gunman kill man in crowded street."

- "Decision reserved in case of justices' pistol permits," New York Tribune, Feb. 25, 1922, p. 7; "Permits by justices to carry guns valid," New York Evening World, March 2, 1922, p. 2.

- Thompson and Raymond, p. 17, 355.

- "10,000 guarded in Frank Yale's $50,000 burial," New York Evening Post, July 5, 1928, p. 18; "Drastic shake-up nears for police," New York Times, July 3, 1928.

- "Flatbush citizens call on Woodin to remove Drummond," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 24, 1922, p. 4.

- "Shot dead for another," New York Times, July 9, 1923; "Frank Yale saved again in gang feud; friend shot dead," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 9, 1923, p. 18.

- Thompson and Raymond, p. 102-103; Pasley, p. 55-58, 239-240; "Drastic shake-up nears for police;" "1,000 suspects seized by Chicago police," New York Times, Nov. 17, 1924.

- Death Certificate of Domenico Ioele, Borough of Brooklyn, City of New York, No. 5159, March 3, 1926.

- "Give up monument at Uale son's request," Brooklyn Standard Union, March 12, 1926, p. 6.

- "Drastic shake-up nears for police."

- "Ruby Goldstein stops Cecolli in first round," Brooklyn Standard Union, May 3, 1927, p. 11.

- "10,000 guarded in Frank Yale's $50,000 burial;" "Drastic shake-up nears for police;" "Gangster shot dead in daylight attack," New York Times, July 2, 1928, p. 1. Yale's second wife was also referred to as "Lucretia" in the press. While it seems Yale began a divorce of Mary before his second marriage, the divorce was not yet finalized.

- "Drastic shake-up nears for police."

- Gentile, Nick, Vita di Capomafia, Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1963, p. 96-97.

- "Question gangster in Marlow murder," New York Times, July 19, 1929, p. 16. Police questioning Masseria in summer of 1929 noted that he gave the same home address as Anthony Carfano: 65 Second Avenue in Manhattan.

- "Capone subpoenaed in murder of Yale," New York Times, July 8, 1928, p. 3; "Drastic shake-up nears for police."

- "Drastic shake-up nears for police;" "Uale breaking ground for parochial school," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 2, 1928, p. 3; "In the real estate market: Parochial school to cost $175,000," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 24, 1928.

- "Drastic shake-up nears for police."

- "Capone subpoenaed in murder of Yale."

- "Gangster shot dead in daylight attack."

- "Hunt Yale's slayer at showy funeral," New York Times, July 6, 1928; Frank Uale Death Certificate, Borough of Brooklyn, City of New York, No. 14764, July 1, 1928, filed July 3, 1928; "Uale, gangster, left estate of $3,000 only," New York Times, Oct. 15, 1930.

- "Hunt Yale's slayer at showy funeral."

- "Capone subpoenaed in murder of Yale."

- "Gun that slew Yale traced to Chicago and Capone arsenal," New York Times, Jan. 18, 1930, p. 1; "Yale killed by Chicago gun," New York Sun, Jan. 18, 1930, p. 2; "Police reports clash on fatal Yale bullet," New York Times, Jan. 29, 1930. While this is an interesting connection, it does not appear to be a reliable one. The newspaper reports of the ballistic tests link a machine gun both to the killing of Yale and to the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. However, the initial reports of Yale's murder and the coroner's report state that no machine gun was used. The only machine gun that could be connected with the Yale killing was one discovered nearby in an abandoned car. It had not been fired.

- "Warren rebuffs plea to fight gangs," New York Times, July 12, 1928, p. 1.

- Gentile, p. 80. Capone would not have been involved in the Yale murder without the consent of Masseria. It is probably not mere coincidence that Manhattan-based Masseria was attempting at this time to bring Mafia organizations in Brooklyn and the Bronx under his control. Shortly after Yale's murder, Masseria's longtime rival Salvatore D'Aquila - a declining power in both boroughs - was murdered. Masseria placed the former D'Aquila organization under the leadership of his trusted friend Manfredi "Al" Mineo.

- Thompson and Raymond, p. 355.

- Critchley, David, The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931, New York: Routledge, 2009, p. 161-162.