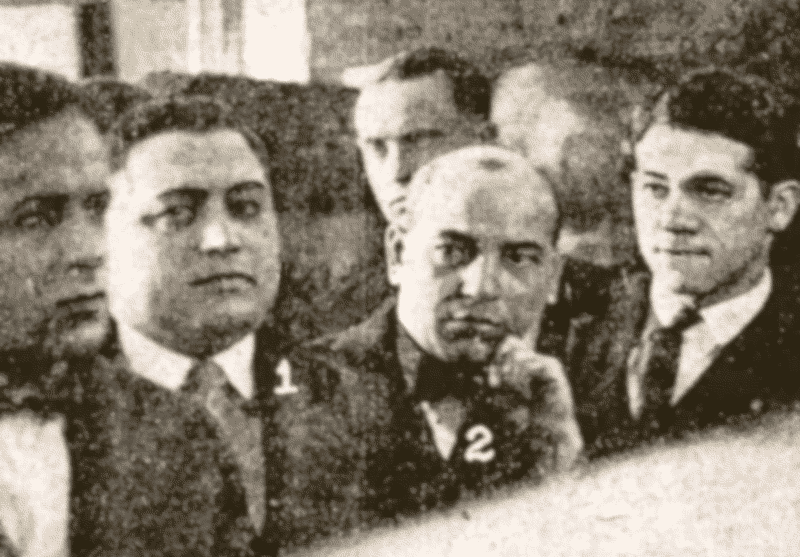

Frankie Yale (1) and Saverio "Sam" Pollaccia (2) sit together in a

Chicago courtroom in 1924, prime suspects in the

gangland slaying of Capone rival Dion O'Banion.

(Chicago Tribune)

The Man in the Shadows: Sam Pollaccia

Some underworld legends, often repeated in mob history books and long cherished by Hollywood, will have to be revised or discarded due to continuing discoveries related to a shadowy Mafia figure named Saverio "Sam" Pollaccia.

Though entirely unknown outside of the small fraternity of Mafia historians (and little known even within it), Pollaccia was a major figure in Prohibition Era organized crime and had a behind-the-scenes role in many of the headline-grabbing events of his day. He quietly rose within New York's Mafia to become a trusted adviser to gangland bosses, and he contributed substantially to the establishment of the nationwide Sicilian-Italian criminal syndicate. Surprisingly, he managed to do all this without drawing much attention from the police or the press.

O'Banion murder

Dion O'Banion

One legend that will require updating is that of Brooklyn gangster Frankie Yale's responsibility for the Chicago assassination of Capone rival Dion O'Banion.1 Sam Pollaccia was, in fact, beside Yale every step of the way.

Yale and Pollaccia were close friends in Brooklyn. Both can be traced to addresses in the center of that borough, around 14th Avenue and Sixth Street. Both also had business interests in Coney Island. Yale ran the Harvard Inn cabaret there, and Pollaccia owned a restaurant on Surf Avenue not far from Nathan's Famous.

An additional connection between them appears to have been membership in the sprawling underworld organization of Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria.

Yale

The two men traveled together by train from New York to Chicago shortly after the Nov. 8, 1924, death of Mike Merlo, prominent leader in Chicago's Italian community. At about the time of their arrival in the Windy City - just two days after Merlo succumbed to cancer - O'Banion was shot to death within his North Side florist shop. He met his end as he prepared arrangements for the Merlo funeral.

A week later, Yale and Pollaccia were preparing to leave for home when a tipster told Chief of Police Collins that they were O'Banion's murderers. The police caught up with the two Brooklynites as they boarded the New York Central Railroad's 20th Century Limited express train at LaSalle Street Station.2

Investigators had little evidence for a case against Yale and Pollaccia and could not punch a hole through their alibi - that they had arrived in Chicago the day following O'Banion's murder. The two men were freed on November 20 and allowed to return to New York.3

New York - Chicago liaison

Legend appointed Yale as the primary contact between the Mafias of New York and Chicago.4 However, that information also appears outdated. Two years after the O'Banion killing, Pollaccia's name was spoken again in Chicago. The context of that mention challenges Yale's legendary position as New York-Chicago liaison.

Tropea

Pollaccia's name turned up as Chicago detectives looked into the murder of Orazio Tropea, a transplanted New York gangster and a member of the Windy City Mafia organization run by the "Terrible" Genna brothers. Tropea's primary responsibility seems to have been that of "collector." He gathered money - by whatever means proved effective - for the Genna organization's legal defense fund, keeping a bit for himself as commission.

Tropea was bumped off reportedly when his commissions grew unreasonably large. Pollaccia was not a suspect in the Tropea killing, but investigators noted his name and address in a book among Tropea's personal effects.

The book contained contact information for dozens of Illinois residents and nine people from out of state. Pollaccia was the only New Yorker listed in the book. Yale's name did not appear. That evidence suggests that Pollaccia was an important connection between the New York underworld and the Genna organization.5

Tropea's Address Book

The Chicago Daily Tribune of Feb. 17, 1926, published the names, addresses and telephone numbers found in Tropea's book. There were 29 entries with Chicago-area addresses and numbers - including a couple for Unione Siciliana leader Antonio Lombardo - and nine for out-of-towners. The nine were:

- Sam Pollaccia of Brooklyn, New York.

- Sam Lovullo of Buffalo, New York.

- James Palese of Detroit, Michigan.

- Sam Pisciatta of Flint, Michigan.

- Vincenzo Piro of Los Angeles, California.

- "Louognino" of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (The newspaper misinterpreted the handwritten name of "Siragusa")

- Miss Gold of South Haven, Michigan.

- Carmelo Brandina, city unknown.

- J. Quattrone, city unknown.

Bronx ambush

Another legend tells that gunmen working for Salvatore Maranzano, leader of a rebel Mafia faction, stumbled unknowingly onto a meeting held by New York boss Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria and killed two top Masseria lieutenants.6 Al Mineo and Steve Ferrigno, loyal Masseria underlings, were shot down Nov. 5, 1930, at the Alhambra Apartments on Pelham Parkway in the Bronx. The shooting occurred during the so-called Castellammarese War.

Sam Pollaccia, never mentioned in histories of the incident, was reported by police to have been at the scene.7 His presence coupled with later evidence that he was conspiring with anti-Masseria forces could explain at last the placement of Maranzano gunmen.

Joe Valachi, one of the Maranzano group, later told federal investigators the names of the participants in the attack. He did not mention Pollaccia.8 It appears that Pollaccia was among the Masseria big shots called to the meeting at the Alhambra Apartments.

Pollaccia's loyalty toward Masseria during this period is suspect. The fortunes of war had turned against "Joe the Boss" so suddenly and so completely that betrayal seems likely. Within New York, a string of surprising Maranzano successes against the boss not only removed valuable Masseria men, but also moved Pollaccia gradually upward in the Masseria chain of command.

Duplicity was hardly unusual in Mafia history. In fact, during the same period, important Mafiosi such as Gaetano Reina, Charlie "Lucky" Luciano and Joseph Profaci also turned out to be paying lip service to Masseria while secretly siding with Maranzano.9

"According to Valachi, the actual shooting [of Mineo and Ferrigno] was done by Buster from Chicago, Girolamo (Bobby Doyle) Santucci, and Nick (Nick the Thief) Capuzzi. All three fired twelve-gauge shotguns. Everyone then scattered. Valachi recalls that afterward Buster was stopped by a police officer about a block from the scene. Buster simply told him that a shooting had taken place down the street. The policeman took off, and so did Buster - the other way."

- Maas, Peter

The Valachi Papers

New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons

1968, p. 92.

Masseria assassination

"Joe the Boss" was violently deposed in a Coney Island restaurant on April 15, 1931, and the legends say "Lucky" Luciano set him up. During a private card game with the boss, Luciano supposedly stepped into the bathroom just as a team of handpicked assassins entered the restaurant. Various underworld figures have been named as participants in the assassination, including Vito Genovese, Joe Adonis, Albert Anastasia and Benjamin Siegel.10

Masseria

The legend, however, turns out to be generally untrue. The boss was known to be lunching that day with Sam Pollaccia, who by that time might have risen as high as underboss or consigliere in the Masseria organization.

Other Masseria lieutenants might have been present, including Luciano. But it was far from a Masseria-Luciano tête-à-tête, and no reliable account of the period mentions the tale of Luciano's conveniently timed trip to the bathroom.

As Brooklyn detectives tried to get to the bottom of Masseria's assassination, they are known to have brought Pollaccia in for questioning. Pollaccia denied any knowledge of or involvement in the killing.11

Some years later, when the Kings County district attorney's office probed the Murder, Inc., organization, it discovered a report that Pollaccia and a small group of men were with Masseria, as "Johnny Silk Stockings" Giustra entered the restaurant behind Masseria and shot the boss to death. None of the other men in the restaurant apparently did anything to interfere with Giustra, who by himself easily could have delivered all five slugs found in Masseria's body.12

Luciano

Giustra was a Brooklyn labor racketeer and possible rival to the organization of Vincent Mangano and Albert Anastasia at the Brooklyn waterfront. Less than a month after Masseria's killing, Giustra was found dead in a Bronx apartment building.13 If that killing was related to Masseria's death rather than to labor racket rivalry, it could be interpreted as an effort by Mafia leaders to remove an individual who linked them with the boss's assassination.

Salvatore Maranzano, victor of the Castellammarese War, assumed the title and responsibilities of boss of bosses of the American Mafia in April 1931. But he, too, was assassinated, gunned down in his Manhattan offices on Sept. 10, 1931.14 The old group of anti-Masseria conspirators looks to have been involved in that killing as well.

Disappearance

Right after Maranzano was dispatched, Sam Pollaccia suddenly disappeared. In Pollaccia's absence, Charlie Luciano became recognized leader of the former Masseria organization and de facto boss of bosses of the American Mafia.

Gentile

In recent years, the old legend of Luciano's 1931 purge against numerous old-time Mafia bosses ("Mustache Petes") across the United States has been widely disputed. Little evidence for that tale exists in obituaries and crime reports. The deaths of just a few known Mafiosi were reported as Luciano took control. The only bosses believed to have been killed in the period were Maranzano and Pittsburgh's Giuseppe Siragusa. However, it now seems that Pollaccia should be added to the list.

Pollaccia's disappearance was a puzzle for law enforcement and a tragic mystery for his wife and five children. However, longtime Mafioso Nick Gentile knew what happened to the former underworld big shot. In the manuscript of his Italian-language autobiography, Vita di Capomafia, Gentile indicated that Luciano underboss Vito Genovese took Pollaccia on a one-way ride to his death in Chicago.

Ricca

The two men stopped off in Pittsburgh to meet with local boss John Bazzano. During the visit, Genovese reportedly confided in Bazzano that Pollaccia would soon be killed and disposed of with the help of Chicago's Paul "the Waiter" Ricca. Bazzano subsequently relayed that information to his close friend Gentile.15

Three quarters of a century have passed since Pollaccia disappeared. Yet only now have we attained a perspective that allows us to see more than the characters long illuminated by history's spotlight and to study the man who was always there in the shadows.

Unlike the Capones and the Lucianos of American organized crime, Saverio Pollaccia did not leave behind an extensive arrest record, a pile of banner headlines or a collection of news photos. He appears never to have been brought to trial for a serious offense. He was only barely noticed by the press. Only hints and brief mentions indicate how important a role he played in the formative years of the national crime syndicate.

Notes

1 McPhaul, Jack, Johnny Torrio: First of the Gang Lords, New Rochelle NY: Arlington House, 1970, p. 209; Balsamo, William and George Carpozi Jr., Under the Clock, Far Hills NJ: New Horizon Press, 1988, p. 189-192. McPhaul attributes the slayings of Jim Colosimo in 1920 and Dion O'Banion in 1924 to the visiting Yale. Balsamo embellished the legend by adding a meeting between Yale and Capone, complete with broken-English dialogue.

2 "N.Y. gangster held by Crowe in gun inquiry," Chicago Tribune, Nov. 19, 1924, p. 1.

3 "Suburb gun centers shut: Two O'Banion suspects are freed," Chicago Tribune, Nov. 21, 1924, p. 1.

4 Peterson, Virgil, W., The Mob: 200 Years of Organized Crime in New York, Ottawa IL: Green Hill Publishers, p. 149-151. Peterson preserves the legend of Brooklyn-based Yale's presidency of the Unione Siciliana organization born in Chicago. He describes Yale as the primary supplier of imported alcohol to the Torrio-Capone gang in Chicago.

5 "Deportation or death seen as gangster fate," Chicago Tribune, Feb. 17, 1926, p. 2.

6 Maas, Peter, The Valachi Papers, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968, p. 92.

7 "Questioned in murder," New York Times, April 20, 1931.

8 Maas, Peter, The Valachi Papers, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968, p. 92.

9 Bonanno, Joseph with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983, p. 84-85, 121-122.

10 Gosch, Martin A. and Richard Hammer, The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975, p. 131-132.

11 "Questioned in murder," New York Times, April 20, 1931.

12 Memo dated Nov. 27, 1940, within the Kings County District Attorney's Office "Murder Inc." files.

13 "Four murders, safe looting in crime flare," Brooklyn Standard Union, May 11, 1931; "Inn owner slain," New York Times, Sept. 12, 1932; "Excerpts from testimony given yesterday at the Crime Commission hearing," New York Times, Dec. 19, 1952, p. 26.

14 "Gang kills suspect in alien smuggling," New York Times, Sept. 11, 1931, p. 1.

15 Gentile, Nick, Vita di Capomafia, U.S. federal government English-language translation of Gentile's unpublished manuscript, p. 115-116. Pollaccia-related passages, obtained through the assistance of author David Critchley, were not included in the published version of Gentile's work