Ignazio "the Wolf" Lupo, an important figure in the New York Mafia into the 1920s, is noticeably absent from histories of the Mafia's Castellammarese War at the start of the next decade. Is it possible that he decided to sit out the conflict?

Lupo in 1910

A major crime family boss at the time of his 1910 imprisonment for counterfeiting, Lupo emerged from Atlanta Penitentiary in the summer of 1920, just in time to become a focus of an underworld struggle between the Morello-Lupo underworld faction and reigning boss of bosses ("capo dei capi") Salvatore "Toto" D'Aquila. The war against D'Aquila coincided with the rise of Manhattan-based boss Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria. Working closely with Lupo in-laws Giuseppe Morello (a former boss of bosses who lost his position when he was imprisoned with Lupo for counterfeiting) and Ciro Terranova, Masseria attained the coveted boss of bosses position upon D'Aquila's 1928 murder. Almost immediately, a new conflict erupted, with crime families across the U.S. rebelling against Masseria. Morello, Terranova, their Catania relatives and their allies generally sided with "Joe the Boss." But Lupo's alignment and activities during the 1930-31 Castellammarese War remain unknown.

The October 1930 murder of Ruggiero Consiglio in Brooklyn was the only noteworthy incident to which Lupo was linked. And some insist that it is proof that Lupo remained a significant underworld figure in the period. However, it is not entirely certain that Consiglio's murder was related to the Castellammarese conflict. It is even less certain that Lupo played any part in the killing.

Ruggiero "Roger" Consiglio, forty-seven, and his younger brother Arturo "Arthur," forty-four, spent much of Wednesday, October 8, 1930, driving around southern Brooklyn. They traveled in separate cars. The reasons for their activity and for their use of different vehicles were not firmly established. Late in the day, when questioned by police, Arthur said they had been visiting Roger's "long list of acquaintances" in an effort to drum up customers for Arthur's insurance business. [1]

New York Times, Oct. 9, 1930

Arthur was known to work as an insurance broker, so that was a plausible explanation, though perhaps not the only one.

Both of the brothers had arrest records. Roger, under the alias of Frank Lanna, had been arrested four times. He faced charges of assault, confidence work, grand larceny, robbery, but was never convicted. Arthur had been arrested a number of times in New York, Newark and Chicago, and served a six-month prison sentence for illegal possession of a firearm [2]. Their troubled histories with the authorities made Arthur's voluntary statement to the police somewhat suspect. That they might have been visiting Roger Consiglio "acquaintances" was an intriguing suggestion. Roger knew some very interesting people, but we'll get to them in a moment.

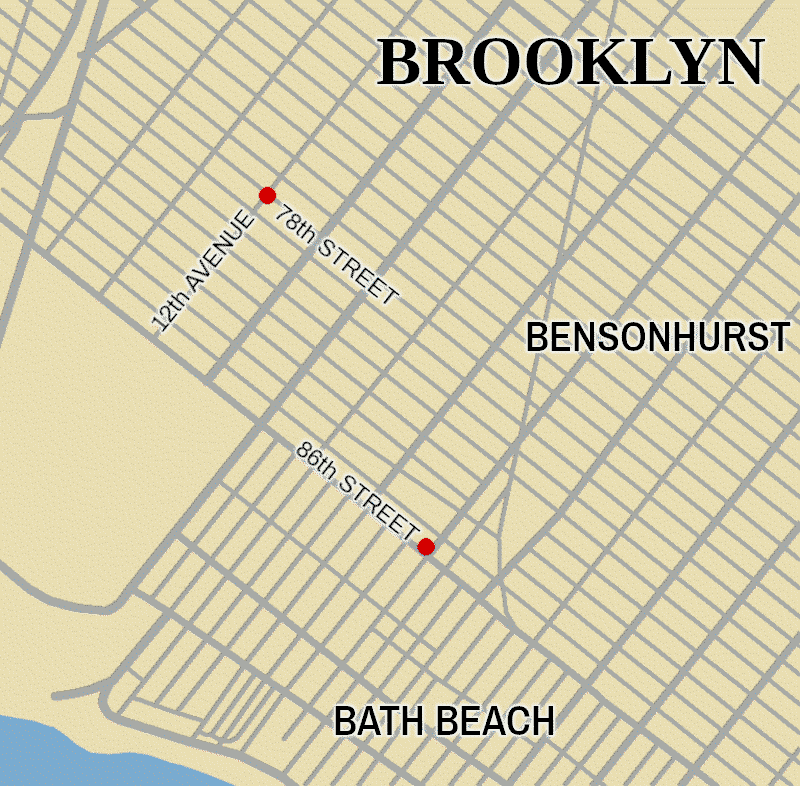

At about six o'clock, the men were on Eighty-Sixth Street, traditional dividing line between the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bensonhurst and Bath Beach, when they decided to call it a day and head home. Both men's homes sat in roughly the same direction, northeast, though Roger lived at 2502 Cortelyou Road in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, and Arthur lived farther away at 138-39 Centreville Avenue in Aqueduct, Queens. [3]

One report stated that they first intended to stop at a nearby bakery to buy bread before heading home for dinner. [4]

Their cars were in close proximity when a tire on Roger's car suddenly went flat on Eighty-Sixth Street. Both brothers pulled to the side of the street opposite Milton Green's service station at 1689 Eighty-Sixth Street. Green was called over and immediately set to work on the tire, with the Consiglio brothers waiting nearby.

Another car pulled in behind the Consiglios. Two gunmen emerged and fired at the brothers, before getting back into their car and driving off. [5]

Patrol Officer Charles E. Weiss was the first on the scene and soon was accompanied by detectives from the Bath Beach Police Station. Dr. Schulman was summoned from Harbor Hospital of Bath Beach, about a half mile away. The physician found Roger Consiglio dead and Arthur Consiglio suffering with a bullet wound to the shoulder. Arthur was taken to Harbor Hospital, where he was treated and questioned. He claimed to know no reason his brother would be targeted by killers. [6]

Milton Green had little to say about the incident. He was busy with the tire, as the shooting occurred and looked up just in time to see two men climbing back into a car and speeding away. He provided police with a description of the car. [7]

Police quickly decided that Roger Consiglio had been the target of the gunmen and Arthur Consiglio's shoulder wound was accidental. [8]

An autopsy conducted by Medical Examiner E.E. Martin showed that the gunmen had made a determined effort to murder Roger Consiglio. Martin found that Roger had been struck by six bullets. Three slugs cracked through the right side of his skull, one struck his chin, two others left holes in his wrist, possibly as he instinctively raised his arm to shield himself from the attack. [9]

The press noted that southern Brooklyn was becoming a gangland battleground. Considered the former territory of Frankie Yale, murdered in 1928, the region was often in the news for bloody incidents. The most recent was the murder of Carmine Piraino, taken out by multiple gunshot wounds to the head. It occurred just two days earlier and a few blocks southeast of Green's service station. Carmine Piraino was the son of gangland chief Giuseppe "The Clutching Hand" Piraino, who had been murdered in the Carroll Gardens section of Brooklyn half a year earlier. [10]

Arthur Consiglio as he's placed in an ambulance (Brooklyn Home Talk)

Arthur Consiglio, daughter (left) and wife after being questioned by Brooklyn police (Brooklyn Standard Union)

Shortly after midnight, Patrol Officer Anthony Ross of Brooklyn's Fort Hamilton Police Station found a Studebaker coupe, abandoned with its motor running at Twelfth Avenue and Seventy-Eighth Street. That location was about a mile northwest of the scene of Roger Consiglio's murder.

Searching the car, police found three handguns. One was fully loaded, one was completely empty and the third contained three unfired cartridges. They decided that the coupe was the Consiglio murder car.

Investigation determined that the coupe had been reported stolen about a week earlier. Its license plates apparently had been switched with plates stolen from a Ford automobile just hours before the shooting.

A fourth handgun - empty - turned up at Eighty-Sixth Street and Eighteenth Avenue, about two blocks southeast of the murder scene. [11]

Detectives expressed the hope that fingerprint evidence from the car or the weapons might lead to the killers. [12]

The October 9 newspapers in the city reported that a list of Roger Consiglio associates had been found in the dead man's pocket. Names on that list reportedly included Ciro "Artichoke King" Terranova, Anthony "Little Augie Pisano" Carfano and Giuseppe Florina. [13]

Terranova was by then a well known rackets boss in Harlem and the Bronx. Carfano was just as well known and for similar reasons in Brooklyn. Both of those men were trusted lieutenants of "Joe the Boss" Masseria. Florina, believed to be an underworld assassin, had been arrested following the murder of Giuseppe Piraino. A decade earlier, Florina and pal Albert Anastasia were convicted of the May 16, 1920, murder of longshoreman Joseph Terella. Sentenced to be executed, they won a new trial on appeal, and they were discharged in the spring of 1922.

Arthur Consiglio explained to police that the names on the list were of people who were to be invited to a family wedding. (Possibly an indication that Arthur was running out of plausible explanations, he said that Roger's recent trip to Italy was to attend a family wedding.) [14]

Map shows locations of Consiglio murder (red dot at lower right) and abandoned getaway car.

Roger Consiglio was born Ruggiero Consiglio on March 2, 1883, in Palermo. His parents were Luigi and Concetta Bramante Consiglio. He entered the United States through Canada as a young adult in 1904, following his younger brother Arthur, who had taken a similar path a year earlier. In the summer of 1910, Roger and Eleonora "Nora" Gilio married in Brooklyn. [15]

Roger Consiglio in 1920

It appears the couple resided for a time in East Harlem, where Consiglio was partner in a liquor business and became a U.S. citizen. Addresses of 1626 Lexington Avenue, 311 East 106th Street and 211 East 106th Street (an address also used by brother Arthur) are associated with Roger in the period between 1917 and 1923.

He did a fair amount of traveling in the final decade of his life. Trips to Italy were documented by returns to the U.S. in August 1920, October 1925, August 1929 and September 1930. [16]

By the time of his 1925 return, he and his wife were Brooklyn residents. The passenger manifest of the S.S. Mauretania, which arrived in New York on October 30, 1925, indicated that Roger was heading home to 371 Eighty-Fourth Street in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. [17]

He was accompanied by his wife during his 1929 trip abroad. They returned on the S.S. Conte Grande, reaching New York on August 5 and then heading to 131 Union Street in the same Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, neighborhood where Giuseppe Piraino was murdered the following spring. [18]

Eleonora traveled with him again in 1930. The couple reentered the U.S. at New York on September 23, 1930. They reported a home address of 609 Neck Road (Gravesend Neck Road) near the intersection with Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. [19] That address was close to busy Mafia territories in Coney Island.

Roger Consiglio lived only a couple more weeks. But they likely were very busy weeks. If he was involved in the Masseria Mafia organization, like his "acquaintances" Terranova and Carfano, he would have spent some of that time getting up to speed on the recently erupted Mafia civil war, helping to organize forces loyal to Masseria and working to identify the opposition. Apparently, he also moved, as his address at the time of his death was the more remote Cortelyou Road location, about four miles north of Neck Road. It would have been sensible for Masseria loyalists to relocate and alter their daily routines at that time. On August 15, Masseria's top aide Giuseppe Morello was murdered by unidentified visitors to his East Harlem office.

When the local press reported on the Consiglio murder, it described Roger as a wealthy building contractor. There was reason to believe he was a somewhat unscrupulous, wealthy building contractor. The Brooklyn Standard Union newspaper reported that he was known to have begun construction of a row of houses on Ford Street. That project was never completed due to mechanics liens placed by unhappy subcontractors. Another project, managed by brother Arthur at Ozone Park, Queens, was also troubled. [20] The building development situation had similarities with an early 1900s building racket of Giuseppe Morello. (It is worth considering that these troubled large-scale developments may have displeased some important underworld investors.)

A few days after the murder, New York Daily News reporter Gates Monroe speculated on its cause. Monroe suggested that Consiglio had attempted to force his way into a lucrative underworld racket, supplying grapes to home wine makers in Little Italy neighborhoods of Brooklyn. He also reported that the Consiglio flat tire was "caused by a handful of nails scattered in the roadway." Monroe did not reveal a source for either statement. [21]

New York Daily News, Oct 12, 1930

There was no noticeable activity in the Roger Consiglio murder case until the night of August 27, 1931. In response to the bloodshed of the Castellammarese War, the New York Police had begun conducting nightly roundups of suspected racketeers. Thirty-three suspects were rounded up in Brooklyn on August 27 (the citywide total for the date reached ninety-four). Within that group were several individuals quickly recognized by the New York press:

Police did not reveal the evidence that caused them to suspect Lupo of the Consiglio killing. On the following day, Lupo had his initial arraignment on the murder charge. Lupo gave the court his name, age and address and said he worked as a fruit broker. His fruit broker position may have been linked to the grape racket mentioned by Gates Monroe of the Daily News a year earlier. (Monroe's speculation that Brooklyn's established grape racketeers were responsible for Consiglio's murder may have prompted Lupo's arrest.) The court held Lupo without bail for a hearing scheduled for Monday, August 31. [22]

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Aug. 31, 1931

When the charge against Lupo was brought up that Monday before Homicide Court Magistrate Joseph F. Maguire, Detective Max Black of the Fort Hamilton Station was named as Lupo's accuser. The hearing was quickly concluded with the magistrate dismissing the matter, citing a lack of evidence. [23]

No further information on the case was revealed.

As a result of the quickly dismissed murder charge, there has been lingering confusion over Lupo's supposed conflict with Roger Consiglio. This may stem in part from a Carl Sifakis story about Lupo being stripped of his moneymaking rackets by the forming Mafia Commission. According to the tale, "the emerging national crime syndicate" disapproved of Lupo's strongarm methods and notoriety and pushed him out. Supposedly forced to fend for himself by this disciplinary measure, Lupo and his son set up a bakery protection racket. [24]

Lupo and his son did in fact form a protective bakery union. They attempted to force some bakeries to join it. This got them in trouble with the law later in the 1930s and ultimately sent Lupo back to prison. The start date of the union racket is uncertain.

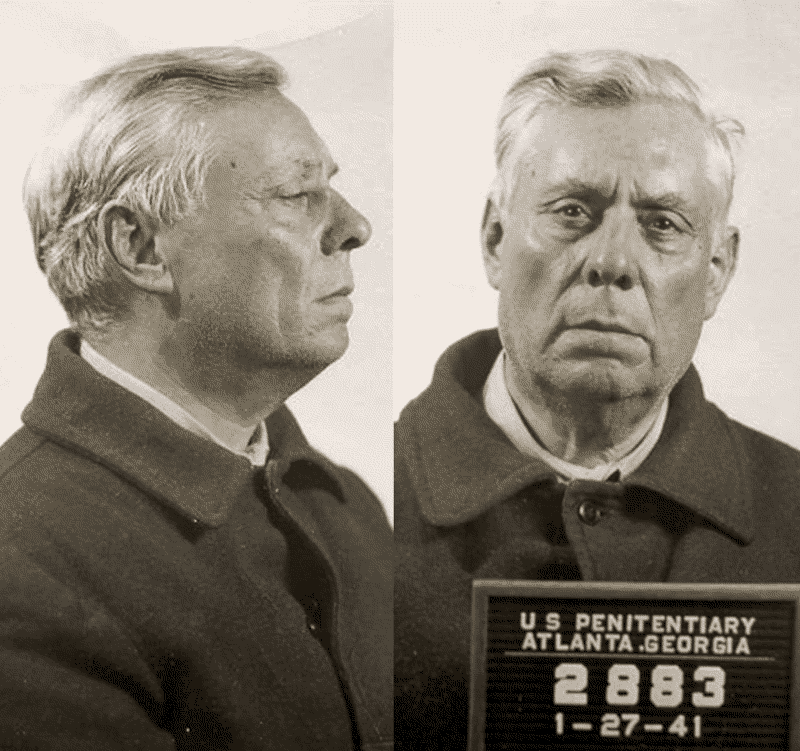

Lupo in 1941

Some merged these things with the Consiglio murder charge and decided that Lupo clashed with Consiglio over Lupo's independent venture. Mike Dickson reported on Americanmafiahistory.com that Lupo, in an effort to recover income lost to Commission discipline, "began extorting local Italian bakeries. On October 8, 1930, he murdered bakery owner Roger Consiglio." [25]

If Consiglio had some investment in a bakery, supporting documentation has been elusive. It's possible, but he certainly was not known as a "bakery owner."

If any action of the Mafia Commission ever caused Lupo to do anything, it could not have been a factor in the murder of Consiglio on October 8, 1930. The Commission or "national crime syndicate" could not have taken any action against Lupo by that date because it would not exist for at least another year. The Mafia was ruled by boss of bosses Giuseppe Masseria until April 15, 1931, and then by boss of bosses Salvatore Maranzano until September 10, 1931. U.S. Mafia families formed the dispute-resolving Commission shortly after Maranzano's assassination.

It is tempting to view Consiglio's murder as a Lupo contribution to a Castellammarese War effort. However, this trail also quickly brings us to a dead end. If Consiglio was involved in the conflict, his list of acquaintances make it seem most likely that he was on the side of Masseria. The known interests of Lupo's in-laws Morello and Terranova, probably would have pulled Lupo toward the Masseria side of the conflict, if he entered it at all.

One possible solution to Consiglio murder puzzle surfaced some time later. It involved Consiglio's aborted real estate development projects in Brooklyn and Queens.

In that theory, Consiglio managed to come into conflict with gangsters who financially backed his real estate ventures or with gangsters who were engaged in rival ventures. [26] It is conceivable that Ignazio Lupo could have been in either of those groups. But if Consiglio was killed over his real estate ventures, his murder would be entirely separate from the Castellammarese War.

A more interesting solution was suggested by informant Joseph Valachi, in his unpublished autobiography. In the early days of the anti-Masseria insurrection, two separate New York underworld factions began acting against "Joe the Boss." These factions were as unknown to each other as they were to their opponent.

Some time after the murders of Giuseppe Piraino and Giuseppe Morello, the groups started to learn of each other and began negotiating over joining forces. Valachi recalled his friend "Buster" telling him about an arrangement reached between a group commanded by Tom Gagliano and one commanded by Salvatore Maranzano:

"...They made a deal between them, after all they got to be sure of one another, so your people gave us a name for us to kill and the old man [Maranzano] gave Tom [Gagliano] a name for you guys to kill and when that was done we got together and now we are working as a team and we are all one." [27]

Either "Buster" did not reveal or Valachi did not recall the names of the two Masseria loyalists killed as a result of this arrangement. Historian David Critchley made an effort to identify them by looking at known gangland homicides in the period immediately following the deaths of Piraino and Morello.

Critchley narrowed the possibilities down to Joseph Bivone, Carmine Piraino, Roger Consiglio and Giovanni Anselmo. Piraino could be ruled out by a March 1932 death-row statement of convicted Mafia killer Peter Sardini. According to Sardini, Piraino's own boss, close Masseria ally Al Mineo, ordered that murder. Of the three remaining, Critchley felt that Consiglio and Anselmo were the most likely targets. [28]

If the slaying of Roger Consiglio was related at all to the Castellammarese War, this deal to cement the alliance between rebellious Gagliano and Maranzano factions appears to be the most likely cause. There appears to be no reasonable way to fit Ignazio Lupo into that scenario.

Following his brother's murder, there were some difficult months ahead for Arthur Consiglio, and not very many of them.

A pair of documents from October 1931 indicate that Arthur attempted then to enter Canada through Buffalo, New York, and was refused permission to do so. The documents show that he continued to report employment as an insurance agent and an address of 138-39 Centreville Street in Queens. [29]

The following summer, he left New York City behind. He relocated to Poughkeepsie, in New York's Dutchess County, around July 1932. It was reported that he was already familiar with the area, particularly the vicinity of Wappingers Falls, just to the south. (He was supposed to have been acquainted with a local man, Joseph Megna, under indictment for murder.) He took an apartment at 551 Main Street in Poughkeepsie [30], but spent much of his time at Joy's Inn, a roadhouse managed by his son Louis on Freedom Plains Road in the Dutchess County town of LaGrange.

On November 3, 1932, federal Prohibition agents arrested Arthur for violating liquor laws. At the time, he attempted to hide his identity behind an alias reported to be "Frank Girordano" (probably "Giordano"). He was scheduled to appear in New York City federal court on January 23, 1933.

Louis drove Arthur to the New York Central Railroad depot in Poughkeepsie on January 19 for his trip into the city. He left his father at the station and never saw him alive again.

Around the start of February, concerned family members went to police and reported that they had not seen or heard from Arthur for weeks. Apparently no one had.

The federal liquor case was postponed until Monday, February 6. Arthur was not present in court. His attorney Percy G. Gellert entered a guilty plea on his behalf. Arthur was sentenced to pay a $15 fine and was permitted two days to make the payment.

A local hunter checking on a line of traps in a secluded area off LaGrange's Schoolhouse Road happened to spot the body of a dead man lying on top of a stone wall. The location was about a half mile from Joy's Inn. The sheriff was summoned. County police and prosecutors were called in. The frozen remains were initially identified by a driver's license in a clothing pocket. Louis was called in to confirm that the dead man was his father Arthur.

Dr. H.P. Carpenter, deputy medical examiner, performed an autopsy. He reported that Arthur had been shot a half dozen times and apparently beaten - his eyes and forehead showed severe bruising. Two bullet wounds were found in the top of his head, another just in front of his left ear. One penetrated the midsection below the heart. One passed through the right chest. The last wounded Arthur's left arm.

The autopsy also revealed that Arthur had eaten a large meal of spaghetti within a couple of hours of his death.

Investigators were unable to determine Arthur's movements after he was left at the train station. The district attorney speculated that Arthur traveled as scheduled to the city and was intercepted by underworld killers posing as friends. Following a spaghetti dinner together, they murdered Arthur and then transported his remains back to LaGrange to serve as a warning to his family.

Arthur's family and Louis's local in-laws were interviewed. None had anything helpful to contribute to the investigation. [31]

1 "Gangsters here slay two more," Brooklyn Citizen, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1.

2 "Contractor, back in country 10 days is ambushed and killed," Brooklyn Home Talk-The Star, Oct. 10, 1930, p. 1; "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Schwartz believes outside gunmen killed Consiglio and left body near home," Poughkeepsie NY Eagle-News, Feb. 9, 1933, p. 1.

3 "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Contractor, back in country 10 days is ambushed and killed," Brooklyn Home Talk-The Star, Oct. 10, 1930, p. 1.

4 "Contractor, back in country 10 days is ambushed and killed," Brooklyn Home Talk-The Star, Oct. 10, 1930, p. 1.

5 "Contractor slain by Bath Beach gang," New York Times, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 29; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Gangland adds 2 more murders to its Brooklyn list," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 23.

6 "Contractor slain by Bath Beach gang," New York Times, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 29.

7 "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1.

8 "Contractor, back in country 10 days is ambushed and killed," Brooklyn Home Talk-The Star, Oct. 10, 1930, p. 1; "Contractor slain by Bath Beach gang," New York Times, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 29.

9 "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1.

10 Giuseppi Piraino Certificate of Death, registered no. 7070, Department of Health of the City of New York, Bureau of Records, Borough of Brooklyn, March 27, 1930; Carmelo Piraino Certificate of Death, registered no. 19637, Department of Health of the City of New York, Bureau of Records, Borough of Brooklyn, Oct. 6, 1930; "Son of 'The Clutching Hand' shot dead; fate of Piraino like that of his father," New York Times, Oct. 7, 1930, p. 31.

11 "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Contractor, back in country 10 days is ambushed and killed," Brooklyn Home Talk-The Star, Oct. 10, 1930, p. 1.

12 "Gangsters here slay two more," Brooklyn Citizen, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1.

13 "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Gangland adds 2 more murders to its Brooklyn list," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 23. Florina was not mentioned in the Daily Eagle's reporting of the list.

14 "Contractor, back in country 10 days is ambushed and killed," Brooklyn Home Talk-The Star, Oct. 10, 1930, p. 1; "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Contractor slain by Bath Beach gang," New York Times, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 29.

15 Ruggiero Consiglio passport application, no. 4424, U.S. State Department, March 24, 1920, issued March 30, 1920; New York City Index to Death Certificates, 1862-1948, certificate no. 19749, Oct. 8, 1930, Ancestry.com; Luigi Consiglio and Concetta Bramante marriage record, Palermo, vol. 59, no. 409, Sept. 7, 1876, Ancestry.com; Arturo Consiglio Petition for Naturalization, no. 139761, Supreme Court of the State of New York, Sept. 28, 1922, certificate 1799226 issued Feb. 8, 1923; New York City Marriage License Indexes, 1907-2018, no. 6902, Brooklyn, June 30, 1910, Ancestry.com; New York City Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937, certificate no. 7751, Brooklyn, Aug. 21, 1910. While both Consiglio brothers entered the U.S. from Canada, Arthur entered by ship, sailing from New Brunswick to Boston, Massachusetts, while Roger traveled from Quebec to New York City on Canada's Grand Trunk Railway.

16 R.L. Polk & Co.'s 1917 Trow's New York City Directory, New York: R.L. Polk & Co., 1917, p. 557; Ruggiero Consiglio, New York County Supreme Court Naturalization Petition Index, 1907-1924, vol. 366, p. 216, Dec. 4, 1919, Ancestry.com; Ruggiero Consiglio passport application, no. 4424, U.S. State Department, March 24, 1920, issued March 30, 1920; Passenger manifest of S.S. Canopic, departed Naples on Aug. 6, 1920, arrived Boston MA on Aug. 20, 1920; Passenger manifest of S.S. Mauretania, departed Cherbourg on Oct. 24, 1925, arrived New York on Oct. 30, 1925; Passenger manifest of S.S. Conte Grande, departed Naples on July 27, 1929, arrived New York on Aug. 5, 1929; Passenger manifest of S.S. Augustus, departed Naples on Sept. 13, 1930, arrived New York on Sept. 23, 1930.

17 Passenger manifest of S.S. Mauretania, departed Cherbourg on Oct. 24, 1925, arrived New York on Oct. 30, 1925.

18 Passenger manifest of S.S. Conte Grande, departed Naples on July 27, 1929, arrived New York on Aug. 5, 1929.

19 Passenger manifest of S.S. Augustus, departed Naples on Sept. 13, 1930, arrived New York on Sept. 23, 1930.

20 "Boro gangster killers elude police," Brooklyn Standard Union, Sports Final, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Slayers trap brothers replacing flat tire at garage in Bensonhurst," Brooklyn Standard Union, Late News, Oct. 9, 1930, p. 1; "Schwartz believes outside gunmen killed Consiglio and left body near home," Poughkeepsie NY Eagle-News, Feb. 9, 1933, p. 1.

21 Monroe, Gates, "Gang gun deaths laid to grape racket feud," New York Daily News, Brooklyn Section, Oct. 12, 1930, p. B4.

22 Seery, John J., letter to B.F. Bates, July 21, 1936, Ignazio Lupo Prison File, #2883, Atlanta Federal Prison, NARA; "Only two crimes reported in 24 hours as police seize 84 suspects in city round-up," New York Times, Aug. 28, 1931, p. 1; "Brooklyn police seize 33 as unrelenting crusade puts crooks to flight," Brooklyn Standard Union, Aug. 28, 1931, p. 1; Cassidy, Tom, "Gang guns peril babies," New York Daily News, Aug. 28, 1931, p. 3; "Head of police orders his aids to curb crime," New York Sun, Aug. 28, 1931, pp. 1, 3; "Mulrooney orders harder crime fight by police officials," New York Times, Aug. 29, 1931, p. 1.

23 Seery, John J., letter to B.F. Bates, July 21, 1936, Ignazio Lupo Prison File, #2883, Atlanta Federal Prison, NARA; "'Lupo the Wolf' is freed in murder; lack of evidence," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Aug. 31, 1931, p. 10

24 Sifakis, Carl, The Mafia Encyclopedia, Third Edition, New York: Facts on File, 2005, p. 282.

25 Dickson, Mike, "Ignazio Lupo - implicated in the early 1900s barrel murders," American Mafia History, americanmafiahistory.com, April 27, 2014, accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

26 "Schwartz believes outside gunmen killed Consiglio and left body near home," Poughkeepsie NY Eagle-News, Feb. 9, 1933, p. 1.

27 Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing: Second Government - The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, 1964, JFK Presidential Library and Museum (online at mafiahistory.us/a023/therealthing.htm), pp. 320-322.

28 Critchley, David, The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931, New York: Routledge, 2009, p. 182.

29 Arturo Consiglio, Canada border crossing manifest, Buffalo, NY, Oct. 15, 1931; Arturo Consiglio, Canada border crossing manifest, Buffalo, NY, Oct. 16, 1931.

30 Zillow.com reports that the three-story apartment building now at that address was constructed in 1900. It may be the building once owned by the Nassar family, where Arthur Consiglio rented an apartment in 1932-1933.

31 "Schwartz believes outside gunmen killed Consiglio and left body near home," Poughkeepsie NY Eagle-News, Feb. 9, 1933, p. 1.