Many of the details in this article were drawn from "The Regina Pacis crowns," Informer, January 2014.

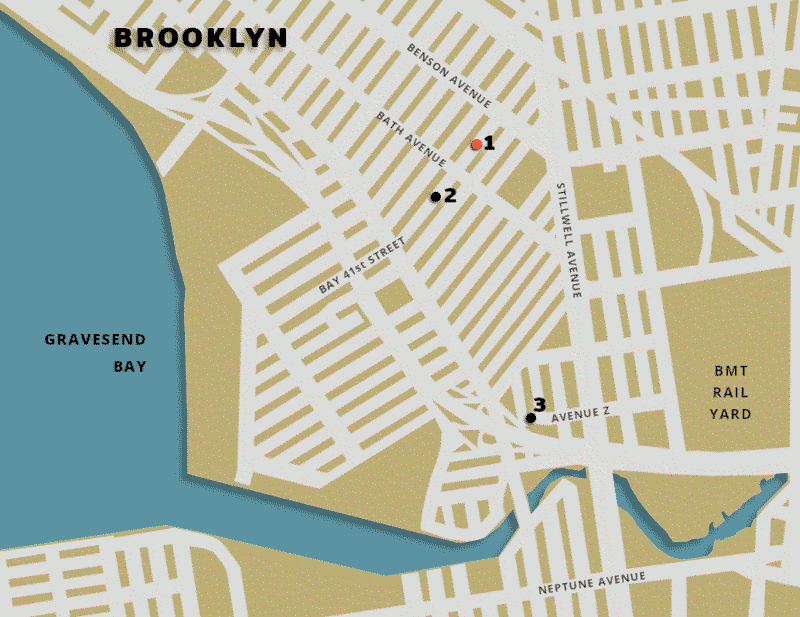

At forty-five minutes past midnight, Wednesday, June 4, 1952, police received an anonymous call telling them of a dead body along Brooklyn's Bay Forty-First Street, between Bath and Benson Avenues. Patrolmen Frederick Frontera and Seymour Ornstein were sent to the location and found a murdered man on the sidewalk.

The body, a male in his prime, had four bullet wounds, two in the chest and two in the head. No identifying information was left with the victim. The spot in Bath Beach was notorious as a dumping ground for gangland murder victims. Police immediately assumed that they were looking at the results of a mob "hit."

The authorities, possibly through information from underworld sources or possibly through memory of earlier encounters with the individual, tentatively identified the victim as thirty-two-year-old Ralph "Bucky" Emmino. [1]

It would soon be understood that Emmino's murder was an example of brutal and capricious Profaci Crime Family discipline, though the profound evil behind it would become attractively packaged within what became known as the "Miracle of Brooklyn." Profaci's death sentence against an obedient subordinate - an act generally dismissed and quickly forgotten by the public - prompted concern within the Gallo brothers' faction of the crime family. The Gallos became increasingly critical of the arbitrary nature of Mafia justice, Mafia loyalty, Mafia morality. Within a decade, a Gallo-led civil war erupted in the crime family, and the killing of Emmino was cited as a cause.

1- Location where Emmino's body was found. 2- Emmino's home address. 3- Longtime Emmino family home just north of Coney Island.

Ralph Emmino

Ralph Emmino was fairly well known in Brooklyn's southwestern neighborhoods. He spent almost all of his life in them.

He was born to Italian immigrant Aniello Emmino and New York-born Mary Russo Emmino on January 1, 1920, in Brooklyn. After an early childhood at 647 Union Street, up in the densely populated Gowanus neighborhood, the family moved to a less congested setting about seven miles to the south at 231 Avenue Z in Brooklyn. The location, a private home where Aniello worked as a farmer, was just across the creek from Coney Island and a short walk from the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit's (BMT) Coney Island train yard. [2]

As a young adult, Emmino married Lillian Morondo and lived for a time with his wife and their son at 1021 Sixty-Sixth Street, near the northern edge of Brooklyn's Dyker Heights neighborhood. When he and Lillian separated, Emmino moved to 223 Bay Forty-First Street in the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn, less than a mile northeast of the longtime Emmino family home and about one block closer to Gravesend Bay than the spot where his lifeless body was found.

Emmino was the second of seven children born Aniello and Mary. Ralph and two of his brothers, Carmine and Jerry, repeatedly got themselves in trouble with the law. [3]

Carmine Emmino

Carmine - Before "Bucky's" murder, Carmine "Moody" Emmino was the best known of the brothers. Born in Brooklyn on February 18, 1924, he was first arrested as a sixteen-year-old. He and three friends were charged with stealing the handles and locks off the end doors of Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit (BMT) subway cars at the train yards, West Twelfth Street and Avenue Z. [4]

Carmine earned a sentence at the reformatory when he was convicted of stealing an automobile. He was paroled twice and sent back to the reformatory twice for violating parole terms. His June 1942 draft registration was filed while he was a resident of Brooklyn's Raymond Street Jail (by then, the street in front of the jail had been renamed to Ashland Place). [5]

In 1946, at age twenty-two, he was charged with assault, robbery and larceny and again locked up in Raymond Street Jail to await trial. [6] On January 2, 1947, he and eight other men succeeded in breaking out of the jail. [7] The escape and the manhunt that followed were covered by regional and national media.

Carmine Emmino was the fifth of the escapees to be recaptured. He surrendered to police shortly before one o'clock in the morning of January 27. [8] After some initial denials, he eventually admitted to helping devise the jail break and to using outside sources to acquire hacksaw blades used in the escape. [9] (It is likely that another of the nine escapees, Alfred "Frank Lee" Minutolo, an accomplished Brooklyn holdup man who had twice escaped from the law previously, had a great deal to do with the escape planning. [10]) Carmine Emmino appeared before Judge Carmine J. Marasco in Kings County Court on February 11, 1947, and pleaded guilty to charges related to the escape. [11] He was sentenced the following month to serve three and a half to seven years in Sing Sing Prison. He was later moved far upstate to the Clinton Correctional Facility at Dannemora. [12]

Jerry - Jerry Emmino was born in Brooklyn at the end of February, 1921. As a young adult, he was outwardly employed as a longshoreman. [13]

Prison officials initially believed that Jerry Emmino, born February 28, 1921, had been responsible for smuggling the hacksaw blades to his jailed brother, but they later established that Carmine Emmino's friend Philip DeCaro posed as Jerry to gain admittance to the Raymond Street facility and deliver the saw blades. [14] Jerry had actually arranged his brother's January 27 surrender through a telephone call to Bath Beach Station detectives. [15]

While cleared of any role in the 1947 jail break, Jerry was soon found to be engaged with a Brooklyn burglary ring. One of the gang members supplied information to the police, and Jerry and his associates walked into a trap on January 11, 1952. They planned to burglarize the Jack Weissman residence in the Malba Gardens section of Queens, but found police waiting for them. As they fled, a police bullet wounded Fortunato "Freddie" Variale, who surrendered. Gang member Joseph Sojack was arrested three days later.

Jerry Emmino remained free until late November, 1952. Aided by an Emmino associate, police detectives were waiting at the Mill Basin Boatyard in Brooklyn and arrested Jerry as he arrived there on November 26. The members of the burglary ring eventually were convicted of assault, robbery and illegal weapons possession charges. [16]

Assistant District Attorney Charles Cahill (seated left) questions accused precious metals robbers (left to right) Gerald Lucadamo, Lawrence Iannacone, Anthony Martinez, Ralph Emmino and Richard Marino.

Ralph - Though, like his brother Jerry, he claimed to work as a longshoreman, [17] by the autumn of 1947, police counted Ralph "Bucky" Emmino as a member of a "loosely-knit gang" of armed robbers based in Brooklyn.

In October, 1947, a police investigation resulted in a raid on a suite in Brooklyn Heights' Hotel St. George and the arrest of three men. Another four believed to be members of the same gang were arrested hours later. They were charged with taking part in a string of armed robberies at jewelry stores and other businesses, as well as some card and dice games, that cost victims a total of $100,000. In a single September 9, 1947, job, the gang was said to have stolen $35,000 worth of gold bullion and platinum bars from a precious metals shop at 11 John Street in lower Manhattan. Police said Ralph Emmino, one of the second group arrested, had been responsible for supplying weapons to the robbers. [18]

When the gold-platinum robbery case went to Felony Court on November 7, metals dealer Thomas Petrucci failed to identify Ralph Emmino and alleged accomplice Richard Marino as the men who robbed him. As a result, the two defendants were both freed. [19]

For some time following Emmino's discharge, police believed him to be a close associate of Joseph "Joe Jelly" Gioielli, enforcer for the Profaci Crime Family-linked Gallo Gang. Raymond V. Martin, a former official of the South Brooklyn detectives, recalled Emmino as Gioielli's "faithful pal." [20]

Numbers gambling was a major racket for the members of the Gallo group, and Emmino may have been involved in numbers running for Profaci Crime Family big shot Calogero "Charlie the Sidge" LoCicero. [21]

Profaci

The Profaci Crime Family (later known as the Colombo Crime Family), ruled since the mid-1920s by Giuseppe Profaci, was especially powerful in South Brooklyn neighborhoods. It had absorbed non-Sicilian gangs in the area, including remnants of Francesco Ioele's (Frankie Yale's) former organization.

Through this expansion, the Profaci group had added members of the Abbatemarco gang, formerly aligned with Ioele. Ioele lieutenant Michael "Mike Schatz" Abbatemarco, like many of his followers, was an American-born descendant of mainland Italian immigrants. (The Abbatemarco family originated in the Province of Salerno, south of Naples.) Upon Ioele's murder, Mike Schatz had his moment in the sun - he moved to a home in Bay Ridge, bought himself a flashy automobile and was widely regarded as the new beer king of Prohibition Era Brooklyn. But that moment lasted only about three months. Early on October 6, 1928, as he drove home from a card game with his cousins Tony and Jamie Cardello and gangster Ralph Sprizza, he was shot to death. [22]

'Frank Schatz'

Profaci welcomed into his organization the Brooklyn non-Sicilians, including Michael Abbatemarco's brother "Frank Schatz," the Cardellos and Sprizza. [23] But the non-Sicilians were kept out of top crime family leadership and decision-making posts. "Frank Schatz" Abbatemarco initially served under Sicilian capodecina Enrico Fontana. Abbatemarco later led his own group in South Brooklyn, where he ran a profitable numbers operation. The young Gallo boys, brothers Lawrence, Joseph "Crazy Joe" and Albert "Kid Blast," and Abbatemarco's son Anthony were included in his gang by the late 1940s and early 1950s. [24]

Ralph Emmino's reported links to both Gallo enforcer Joseph Gioielli and Calogero LoCicero, who was Profaci's consigliere, suggest that Emmino was an associate of the Profaci Crime Family's Abbatemarco faction at the time of his 1952 murder. About a decade after Emmino's murder, a member of the crime family who became a federal informer confirmed the organized crime link. Gregory Scarpa, Sr., who secretly worked with the FBI for decades while remaining a member and hit man in the Profaci/Colombo Crime Family, told agents that "Bucky" was "a good fellow." Scarpa used the term "good fellow" when referring to individuals who were connected with the Mafia. [25]

Early in 1952, a police racket squad arrested Frank Abbatemarco and a number of his underlings, including Anthony Abbatemarco, thirty; Lawrence Gallo, twenty-four; Joseph Gallo, twenty-three; and Carmine Persico, eighteen. They were charged with running a $2.5 million a year policy ring. [26] Emmino was not among those arrested, according to media reports.

Years later, a quarrel erupted between Frank Abbatemarco and Profaci over Profaci's demands for a greater share of the numbers racket income. When Abbatemarco stubbornly halted his tribute payments, according to reports, Profaci ordered the Gallos to murder their superior. They did so in 1959, with Joseph Gioielli reportedly serving as the triggerman, expecting to be rewarded with control of the numbers. Profaci handed the racket over to others closer to him, and the Gallos broke with the boss. [27] But tension between the Gallo brothers and Profaci leadership can be traced back further. And its roots may be found in the 1952 killing of "Bucky" Emmino.

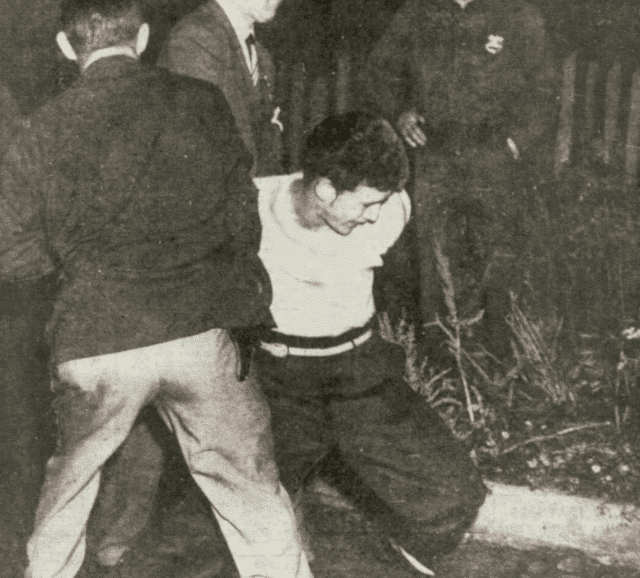

Vincent Emmino is restrained by police after viewing his dead brother.

Detectives located one of Emmino's younger brothers and brought him to the scene to verify the victim's identity. Vincent Emmino, then eighteen, identified Ralph's remains and immediately flew into a rage, swearing he would "get the man" responsible. Vincent needed to be restrained by law enforcement.

Police investigators pieced together Ralph Emmino's movements on the night he was killed. Separated from his wife Lillian and their eight-year-old son, Emmino had been with a twenty-three-year-old girlfriend at a Brighton Beach address early Tuesday night. At seven-forty-five, he told the girlfriend he needed to meet someone and left in a 1950 green Pontiac convertible. The car was registered to Lillian Emmino at her Sixty-Sixth Street address. [28]

Later in the evening, Emmino was seen having drinks at a Bath Beach tavern. Just before midnight, some men approached Emmino and had a brief conversation with him. Emmino and the men then left the tavern together.

Police questioned neighborhood residents, and none reported hearing any gunfire during the night. The green convertible turned up on West Twelfth Street near Highlawn Avenue, a tree-lined residential neighborhood about a mile from the spot where Emmino's body was found. Blood was noted on the floor of the automobile. These details combined to convince police that Emmino had been killed in the car and dumped from the vehicle on Bay Forty-first Street. [29]

There was some early speculation that Emmino gambling debts played a part in his demise, but very quickly law enforcement decided that Emmino was killed as a result of his participation just four days earlier in the theft of two jeweled crowns from a display of the Madonna and Child at the Regina Pacis ("Queen of Peace") Shrine Church. The crowns disappeared from the shrine, at Twelfth Avenue and Sixty-fifth Street, sometime between nine-forty-five Friday evening, May 30, and six o'clock the next morning. [30]

The crowns had been created during World War II from diamonds, rubies and sapphires donated by members of St. Rosalia Church, Fourteenth Avenue and Sixty-ninth Street. The Regina Pacis Shrine Church itself was constructed in the mid-1940s by St. Rosalia parishioners as a memorial to postwar peace. [31]

A number of details suggested the possible link between Emmino and the church burglary. Emmino had previous experience stealing jewelry and precious metals. Emmino would have been well aware of the jeweled crowns at the Regina Pacis shrine. The Sixty-Sixth Street home he had previously shared with his wife and son was part of St. Rosalia's Parish and sat just two blocks from the Regina Pacis Shrine Church. He and his family had been members of the parish - his son received his First Holy Communion at St. Rosalia's Church. A local man reported seeing a green automobile like Emmino's parked near the shrine after the building was locked up late Friday. [32]

The parish's association with organized crime figures was already well established. For many years, Francesco Ioele had been a generous contributor to St. Rosalia. In addition to direct contributions, he organized fundraisers. Ioele participated in the groundbreaking ceremony for St. Rosalia's Catholic School about six weeks before his July 1, 1928, murder. St. Rosalia's Church was the site of Ioele's funeral. Since Ioele's bloody exit, Joseph Profaci, member of a neighboring Catholic parish, had taken over as the parish's underworld patron and protector. Profaci participated in the autumn 1948 groundbreaking for construction of the Regina Pacis shrine. [33]

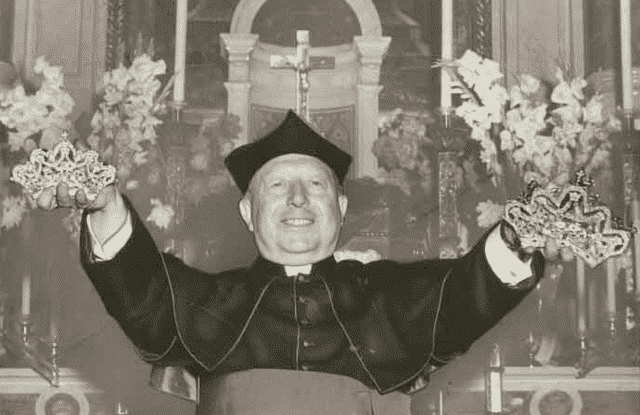

Monsignor Cioffi holds the returned crowns.

Crowns returned - The jeweled Regina Pacis crowns suddenly returned on June 8, 1952. The precious items arrived by Sunday special delivery mail, protected only by a nine-inch by twelve-inch cardboard "Protecto" mailer. The package, addressed to Monsignor Angelo Cioffi at the Regina Pacis shrine church, had three dollars' worth of twenty-five-cent stamps affixed to it. A return address of 400 Broome Street, Manhattan, was written on the mailer. That address was the annex of the New York Police Department headquarters. A postmark indicated that the package was mailed three o'clock Saturday afternoon through a regular mail chute at the main Manhattan post office, Eighth Avenue and Thirty-third Street. [34]

Monsignor Cioffi brought the crowns into Sunday Mass to prove to the members of the congregation that their prayers had been answered. News media heralded the "miracle in Brooklyn" and made no mention of the blood that apparently had been spilled in connection with it. [35]

A number of gems were found to be missing from the crowns, and the crowns themselves had suffered some damage during their handling, but they were carefully repaired and returned to their place in the shrine display. New security measures were installed.

However, the security precautions proved to be less effective than underworld justice. The same jeweled crowns again were stolen from the shrine early in 1973. And, again, they were quickly returned.

The Profaci/Colombo Crime Family was credited with arranging both returns. (Read more about the Mafia's involvement with the Regina Pacis crowns in Informer's issue of January 2014.)

Robilotto

Inside the Profaci Family - The story of Emmino's murder was recalled years later by informant Gregory Scarpa, Sr. A report on the information provided by Scarpa to the FBI indicated that Joseph Profaci, enraged by the theft from Regina Pacis, was responsible both for ordering the return of the crowns and for ordering the murder of Emmino.

The report read: "Informant stated that Profaci had the jewels returned and then ordered Bucky killed. Informant stated that he did not know who killed Bucky, but that it could possibly have been Charles LoCicero, inasmuch as Bucky was running numbers for LoCicero at that time." [36]

The Gallo group was angered by what they viewed as an unjust Profaci-ordered hit against Emmino. The burglar had been ordered to turn over the crowns so they could be sent back to the church, and he did so. That compliance should have guaranteed his safety.

Early in 1961, when emissaries from Joseph Profaci met with the Gallos to determine the cause of their revolt against the boss, the Gallos reportedly cited several murders they believed had been ordered by Profaci for "personal reasons" rather than for business reasons. They mentioned the murders of Ralph Emmino (June 4, 1952), "Johnny Roberts" Robilotto (September 7, 1958) and Frank "Frankie Schatz" Abbatemarco (November 4, 1959). [37]

The Abbatemarco death sentence had the greatest emotional and financial impact on the group. But, for the Emmino killing to be mentioned nearly a decade after it occurred, the Gallos must have considered it a terrible offense. It was certainly the oldest of the grudges described to the emissaries. Given the years of obedient Gallo service to Profaci following the killing, Emmino's murder cannot be called a direct trigger of their revolt. But it appears the incident started the Gallos down a path of finding fault with the Profaci administration that ultimately led to their break with it.

The way of all flesh - Officially, the gangland slaying of Ralph Emmino remained unresolved. With Emmino linked in the public mind to the abhorrent theft of the church jewels, there was little to no public pressure for law enforcement to get to the bottom of it. The general feeling, it seemed, was that Emmino's end had been well deserved. Perhaps Brooklyn's Catholics mentally attached an addendum to the original Ten Commandments, causing "Thou shalt not kill" to diminish in significance beside "Thou shalt not steal" when the stealing was done in a church.

However, the theft of the Regina Pacis crowns was also unsolved. Emmino's role in the crime was supposed but not proven.

According to press reports, the allegations against Emmino were so severe that he was denied a church funeral Mass. Possibly this was a decision made by his surviving family rather than the Brooklyn churches. A service was held in Labella Funeral Home, 2625 Harway Avenue in Brooklyn, before Emmino's remains were taken for burial at St. John's Cemetery in Queens. [38]

Law enforcement was present at the funeral home, as were Emmino's lawbreaker brothers. Carmine was brought from prison to attend the service in handcuffs. Jerry, a suspect in January's attempted burglary of the Weissman residence, was taken into custody immediately after the service and brought to police headquarters for questioning. [39]

Joseph Profaci lived another troubled decade, plagued by law enforcement scrutiny, a civil war in his crime family and worsening health problems. He succumbed to cancer on June 6, 1962, ten years and two days after the murder of "Bucky" Emmino.

Though extreme violence, deceit and theft had been the foundation of his existence, he had attended Sabbath services and had donated generously from his ill-gotten gains to Brooklyn churches. He was granted formal funeral services within a church on June 11, 1962. (Law enforcement was present but reportedly recognized no crime figures in attendance.) Monsignor Francis P. Barilla presided over the Mass of Christian Burial for the Mafia chief at St. Bernadette's.

But, when the forty-five minutes of ceremony concluded, the longtime crime boss was interred at the same cemetery that held the murdered Emmino's remains. [40]

1 Deaths reported in the City of New York, 1952, certificate no. 11282; Doyle, Patrick, and Kermit Jaediker, "Redhead quizzed; bullets stopped date with hood," New York Daily News, June 5, 1952, p. 4; Phelan, Harold, and I. Kaufman, "Shrine theft linked to 'ride,'" Brooklyn Eagle, June 4, 1952, p. 1; George, Joe, "Ride victim dumped in gutter, bullets in head," New York Daily News, June 4, 1962, p. 4; Dugard, Justin, "Colombo Violence Timeline," Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement, January 2012, p. 17.

2 United States Census of 1920, New York State, Kings County, Assembly District 8, Enumeration District 445; United States Census of 1930, New York State, Kings County, Assembly District 16, Enumeration District 24-1434; Ralph Joseph Emmino World War II Draft Registration Card, serial no. S-158, order no. S-3546, Local Board no. 196, Brooklyn, New York, July 1, 1941.

3 The second-, third- and fourth-born of six brothers had trouble with the law. Their father Aniello Emmino was born in Italy on November 27, 1898, and died in April 1962. Their mother Mary Russo Emmino was born about 1900. Aniello immigrated to the U.S. in 1917. The couple was married December 2 of that year at Brooklyn. (See: "Emmino," New York Daily News obituary, April 10, 1962, p. 38; Aniello Emmino World War II Draft Card, serial no. T-1188, order no. T-11066, Local Board no. 196, Brooklyn, New York, Feb. 15, 1942; United States Census of 1920, New York State, Kings County, Assembly District 8, Enumeration District 445.)

4 Carmine Joseph Emmino World War II Draft Registration Card, serial no. N-563A, order no. 12323A, Local Board no. 196, Brooklyn, New York, June 30, 1942; "4 boys charged with stripping subway trains," Brooklyn Citizen, Dec. 7, 1940, p. 2; "Four boys held in theft of subway train parts," Brooklyn Eagle, Dec. 7, 1940, p. 1.

5 "Six in break began crimes as youths," New York Times, Jan. 3, 1947; "From door-knob theft to dice-game murder," New York Post, Jan. 3, 1947, p. 5.

6 "Fifth Brooklyn fugitive in jail after surrender," New York Sun, Jan. 27, 1947, p. 15.

7 "2 fugitives hunted in N.J.; 3d is reported seen in boro," Brooklyn Eagle, Jan. 3, 1947, p. 1; Berger, Meyer, "City-wide hunt on," New York Times, Jan. 3, 1947, p. 1; O'Brien, Michael, and Neal Patterson, "FBI aids as clues fail in hunt for jail gang," New York Daily News, Jan. 4, 1947, p. 3; "Inside story of jail break told; four prisoners framed the plot," New York Sun, Jan 10, 1947, p. 1.

8 "5th jail fugitive gives self up in Brooklyn," New York Post, Jan. 27, 1947, p. 5; "D.A., jury launch wide jail inquiry," Brooklyn Eagle, Jan. 27, 1947, p. 1; "5th jail fugitive surrenders here," Brooklyn Citizen, Jan. 27, 1947, p. 1.

9 "Sawing of jail bar began months ago," New York Times, Jan. 7, 1947; "Third jail-breaker seized in Brooklyn," New York Times, Jan. 21, 1947; "Fifth in jailbreak gives up to police," New York Times, Jan. 27, 1947; Lieberman, Irving, and Alice Davidson, "5th jail fugitive gives self up in Brooklyn," New York Post, Mon., Jan. 27, 1947, p. 5; "Jail breaker admits saw blade was smuggled in by a friend," New York Times, Jan. 28, 1947; "Jailbreak quiz is focused on smuggled saw," Brooklyn Eagle, Jan. 28, 1947, p. 1; Kiernan, Joseph, and James Desmond, "Escapee gives up, admits he saw cut bars," New York Daily News, Jan. 28, 1947, p. 8. Emmino's friend Philip DeCaro was charged with smuggling the saw blades into the jail and later confessed. (See: "Held in jail break case," New York Times, Feb. 6, 1947; "Cone lauds police for rounding up of jail fugitives," Brooklyn Eagle, Tues., April 15, 1947, p. 22.)

10 "Escapes cops by leap off train," New York Sun, Aug. 7, 1946; "From door-knob theft to dice-game murder," New York Post, Jan. 3, 1947, p. 5; "False tips plague cops in hunt for fugitives," Brooklyn Eagle, Jan. 5, 1947, p. 1.

11 "3 jail breakers guilty," New York Times, Feb. 12, 1947.

12 "Jail breaker sent to prison," New York Times, March 7, 1947; "Jailbreaker gets Sing Sing stretch," New York Daily News, March 7, 1947, p. 22; "Act to restore Madonna's crowns," New York Daily News, June 10, 1952, p. 5.

13 Births Reported in 1921 - Borough of Brooklyn, E, p. 313, certificate no. 13544; Jerry Emmino World War II Draft Registration, serial no. T-391, order no. T-11405, Local Board no. 196, Brooklyn, New York, Feb. 16, 1942; United States Census of 1940, New York State, Kings County, Assembly District 16, Enumeration District 24-1894. The birth record indicates a birthdate of Feb. 27, 1921, but Jerry Emmino reported a birthdate of Feb. 28, 1921, on his draft registration.

14 "2 more in break captured in raid," New York Times, Feb. 2, 1947.

15 "Jail fugitive's kin calls cops and No. 5 gives up," New York Daily News, Jan. 27, 1947, p. 3.

16 "Third man arrested in Whitestone burglary," Long Island Star-Journal, Nov. 26, 1952, p. 1; "'Burglar' held after 3 years," Long Island Star-Journal, Feb. 26, 1955, p. 2.

17 United States Census of 1940, New York State, Kings County, Assembly District 16, Enumeration District 24-1894.

18 "Cops round up 7 in raids to solve $100,000 thefts," Brooklyn Eagle, Oct. 17, 1947, p. 1; "Bail rough on 7 toughs in rob mob," New York Daily News, Oct. 18, 1947, p. 4.

19 "Fails to identify pair in gold theft," New York Daily News, Nov. 8, 1947, p. 6.

20 Martin, Raymond V., Revolt in the Mafia: How the Gallo Gang Split the New York Underworld, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1963, p. 69.

21 SAC New York, "[Deleted] Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program New York Division," FBI memorandum to Director, file no. 179-1996-15, Aug. 31, 1962, p. 10, see Gregory Scarpa Sr. files, Part 1, p. 69, Internet Archive, archive.com; Lance, Peter, Deal With the Devil: The FBI's Secret Thirty-Year Relationship With a Mafia Killer, William Morrow, 2013, Kindle version, Chapter 7.

22 "Uale's successor slain in auto by lone gunman, jealousy in gang hinted," Brooklyn Standard Union, Oct. 6, 1928, p. 1; Daniell, F. Raymond, "Yale successor slain near place where chief died," New York Evening Post, Oct. 6, 1928, p. 1.

23 Feather, Bill, "Colombo Family membership chart 1930-50s," Mafia Membership Charts, mafiamembershipcharts.blogspot.com, Nov. 9, 2017; Feather, Bill, "Bios of early Colombo members," Mafia Membership Charts, mafiamembershipcharts.blogspot.com, Jan. 16, 2016.

24 See also our brief biography of Frank Abbatemarco: "Who Was Who: Abbatemarco, Frank (1899-1959)."

25 SAC New York, "[Deleted] Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program New York Division," FBI memorandum to Director, file no. 179-1996-15, Aug. 31, 1962, p. 10.

26 "Raids smash $2,500,000 policy ring," Brooklyn Eagle, March 26, 1952, p. 1.

27 Raab, Selwyn, Five Families: The Rise, Decline and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006, pp. 322-323; Martin, Raymond V., Revolt in the Mafia: How the Gallo Gang Split the New York Underworld, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1963, pp. 30-31; Teresa, Vincent, with Thomas C. Renner, "Crime flourishes as the family's octopus spreads," Ottawa Canada Journal, Aug. 29, 1973, p. 17; Krajicek, David J., "Frankie Abbatemarco is the opening casualty in the Profaci family civil war," New York Daily News, Sept. 19, 2010.

28 Doyle, Patrick, and Kermit Jaediker, "Redhead quizzed; bullets stopped date with hood," New York Daily News, June 5, 1952, p. 4; Phelan, Harold, and I. Kaufman, "Shrine theft linked to 'ride,'" Brooklyn Eagle, June 4, 1952, p. 1.

29 "Fingerprints probed in slaying of hood," Brooklyn Eagle, Thursday, June 5, 1952, p. 3; Phelan, Harold, and I. Kaufman, "Shrine theft linked to 'ride.'" Brooklyn Eagle, June 4, 1952, p. 1.

30 "Link gang killing to crown theft," Newsday, June 4, 1952, p. 5; "No gang-style funeral pomp for ride victim," New York Daily News, June 6, 1952, p. 14; "100,000 altar gems stolen from new Brooklyn church," New York Times, June 01, 1952, p. 1; Leiner, Al, and Clarence Greenbaum, "150,000 jeweled crowns stripped from boro shrine," Brooklyn Eagle, Sunday, June 1, 1952, p. 1.

31 "Pope blesses gems for Brooklyn shrine," New York Times, Jan. 13, 1952; "Bishop Kearney lays cornerstone at peace shrine," Brooklyn Eagle, Oct. 30, 1949, p. 4; "Shrine dedicated; 7,000 at services," New York Times, Aug. 16, 1951.

32 "Green car linked to shrine robbery," New York Times, June 2, 1952; "Green sedan clue in shrine looting," Brooklyn Eagle, June 2, 1952, p. 1; "Fingerprints probed in slaying of hood," Brooklyn Eagle, June 5, 1952, p. 3.

33 "Ruby Goldstein stops Cecolli in first round," Brooklyn Standard Union, May 3, 1927, p. 11; "Uale breaking ground for parochial school," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 2, 1928, p. 3; "Hunt Yale's slayer at showy funeral," New York Times, July 6, 1928; "Gangs gather as pals bury Frank Yale," Yonkers NY Statesman, July 5, 1928, p. 2; "50,000 mark start of $1,000,000 shrine," Brooklyn Eagle, Oct. 4, 1948, p. 2. Reports indicate that Profaci's home church, also supported by him, was the Shrine Church of St. Bernadette, on Thirteenth Avenue between 82nd and 83rd Streets, about three-quarters of a mile from St. Rosalia's Church.

34"Church gets stolen gems in mail; pastor hails recovery as miracle," New York Times, June 9, 1952, p. 1; "Prayer answered as stolen jewels return to church," Stars and Stripes (AP), June 9, 1952, p. 1; Frigand, Sid, "Shrine gem thieves hunted," Brooklyn Eagle, June 9, 1952, p. 1; Fried, Joseph R., "$350,000 in gems stolen from altar of Brooklyn shrine," New York Times, Jan. 11, 1973; "Regina Pacis and the case of the missing crowns," Brooklynology, Brooklyn Public Library website, Aug. 5, 2009, accessed Dec. 26, 2012.

35 Kanter, Nat, and Henry Lee, "100G shrine gems mailed back," New York Daily News, June 9, 1952, p. 3; "Stolen $100,000 crowns returned, parish exults," Newsday, June 9, 1952, p. 5; Lushbaugh, Gene, "People of all faiths elated over 'miracle,'" Brooklyn Eagle, June 9, 1952, p. 1. An eighteen-year-old Dom DeLuise, just beginning an entertainment career that would span most of the next six decades, was quoted in the Brooklyn Eagle article. He spoke of the reaction of his mother, who attended the Mass in which Monsignor Cioffi first revealed the returned crowns: "My mother had been to 10 o’clock Mass. She burst into the house and cried out, ‘They’re home, they’re home,’ and boy, she was really crying."

36 SAC New York, "[Deleted] Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program New York Division," FBI memorandum to Director, file no. 179-1996-15, Aug. 31, 1962, p. 10, see Gregory Scarpa Sr. files, Part 1, p. 69, Internet Archive, archive.com.

37 Martin, Raymond V., Revolt in the Mafia: How the Gallo Gang Split the New York Underworld, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1963, pp. 68-69, 105. Martin referred to Ralph "Bucky" Emmino as "Jimmy 'Bucky' Ammino" and later as "Alfred Ammino." According to Martin, the Profaci emissaries were Calogero LoCicero and a Don Lorenzo, elderly owner of Trenton Linen and Supply.

38 "No gang-style funeral pomp for ride victim," New York Daily News, June 6m 1952, p. 14; "Act to restore Madonna's crowns," New York Daily News, June 10, 1952, p. 5.

39 "Act to restore Madonna's crowns," New York Daily News, June 10, 1952, p. 5.

40 "Profaci dies of cancer; led feuding Brooklyn mob," New York Times, June 8, 1962; Federici, William, and Neal Patterson, "Profaci rubbed out by cancer," New York Daily News, June 8, 1962, p. 5; "S'long, Joe, the cops wonder wacha know," New York Daily News, June 12, 1962, p. 2; Hunt, Thomas, "1962: Cancer claims mob boss Profaci," Writers of Wrongs, writersofwrongs.com, June 6, 2021.