Editor's note: The following article - one of a series of "Just One More Thing" columns - was first published in the June 2015 issue of Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement.

There are a number of unanswered questions related to the American Mafia's incorporation of Calabrian gangsters - those who trace their origins to the southernmost portion of the Italian mainland. We may ask: How did this combination occur? Precisely when did it occur? Was it the result of a decision of the American Mafia as a whole or did it result from decisions of individual crime families? Were Calabrian gangsters welcomed on an individual basis or was a Calabrian crime network consumed by the Mafia en masse?

This last question touches on a subject that I have found particularly interesting: Was there a distinct, organized Calabrian criminal network in the United States and Canada before Calabrian gangsters were absorbed into the known Sicilian-based Mafia crime families?

We may never find definitive proof that such a network was incorporated into the Mafia or even that it existed at all, but it may help to consider what types of evidence could be considered proof.

To suggest the existence of the network, we would need to see exclusively Calabrian criminal groups in various regions, we would need to see links among the groups, and it would help if we found some sort of collective administration among or over them. To determine if and when a merger with the Sicilian Mafiosi occurred, we would need to establish that there was a time when no bond existed between organized Calabrian and Sicilian racketeers and that there was a time when they functioned within a single criminal entity and shared common rules, endeavors and hierarchy.

The idea that immigrant Calabrian criminals would tend to associate with other immigrant Calabrian criminals simply makes sense. In general, early immigrant communities in the U.S. were tightly knit and insular. Italian-American communities often experienced bonding based not merely upon common nationality but upon common original region, province and hometown. And these Italian birthplace bonds appear to have been more important to new immigrants than their physical locations in their adopted homeland.

This has been shown to be true for American Mafia organized crime, in which the earliest units were comprised of individuals from the same background and often the same bloodlines, even when the individuals happened to live great distances from each other in the U.S. A clear example of this occurs among the early U.S. Mafiosi from Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily, whose feeling of common interest was unaffected by the great distances between their American home cities. Considering these things, we would be justified in assuming that Calabrian organized criminals, in their earlier years in the United States, also tended to trust in and rely on each other more than "outsiders."

But more than just a logical argument stands in support of the existence of Calabrian gangs and broad criminal networking. We have examples of Calabrian organized criminals teaming with their fellow Calabresi (and sometimes Lucani from the neighboring Basilicata region in southern Italy) even in illegal ventures that extend through several regions of their adopted American and Canadian homelands. In these sprawling crime rings, we often find members linked by kinship and/or very close Italian roots. We see suggestions of administration over the various groups. And we detect moments before and after cooperation with other organized crime groups is established.

Rocco Racco of western Pennsylvania

A glimpse of a Calabrian organized crime network was provided by law enforcement's crackdown on a Black Hand extortion ring operating in western Pennsylvania in the early 1900s.

At the time, the village of Hillsville, Pennsylvania, northwest of Pittsburgh and just over the state line from Youngstown, Ohio, drew in large numbers of immigrant southern Italians for work at its limestone quarries. A large percentage of the Italian labor force was from the region of Calabria. A Calabrian extortion and labor racketeering ring, known by such names as "The Society" and "The Family," grew in the area and preyed on the hard-working population.

Francis Dimaio

A leadership quarrel in The Society (reportedly exacerbated by differences of opinion over whether to back management or labor in a 1905 quarry workers strike), coupled with the shooting deaths of two well-known non-Italian area residents, led law enforcement, the local business community and the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to join forces to expose and eradicate the criminal organization. Information obtained by undercover Pinkerton operatives, including veteran Francis P. Dimaio, and successful prosecutions by District Attorney Charles H. Young provided a window into the Calabrian underworld society.

The Society in Hillsville was led for some time by a boss with the euphonious name of Rocco Racco. In that endeavor, he had the support of a number of his relatives. The Racco family, originally from the Grotteria community of Reggio Calabria, emigrated to the U.S. in the 1890s. Some family members settled in western Pennsylvania, while others made their homes in Brooklyn, in upstate New York and in Ontario, Canada.

Racco's larceny trial in March of 1907 brought to light the inner workings of his organization. The court heard that Racco recently had been deposed as "Black Hand" leader due to complaints by rivals Fred Surace and Joe Bagnato. Those complaints reportedly were reviewed by a panel of underworld leaders, presumably Calabresi, from other communities, including Buffalo and New York City. Meeting in Hillsville, the panel found Racco guilty of abusing his authority and of committing adultery with the wife of a Society member. He managed to avoid (rather, to postpone) a death penalty by stepping down as boss and providing large cash payments to Surace and Bagnato.

While Racco was serving a year prison sentence for larceny, much of his organization was arrested, tried and convicted of an assortment of crimes, including assault, robbery, carrying concealed weapons and extortion. Bagnato avoided arrest reportedly by fleeing back to Italy. But Surace, Salvatore "Sam Kennedy" Candido, Joe Catrone, Joseph and Frank Calaute, Jim and Felice Racco, Nick Sanati, Rocco Panetta and Dominick Bertillo were among those imprisoned.

Seely Houk

In May of 1908, Racco was formally charged with the 1906 murder of Pennsylvania Deputy Game Warden Seely Houk. There were suggestions that he killed Houk out of revenge for Houk's killing of Racco's favorite hunting dog or as part of an effort to restore his reputation with The Society. (For various reasons, Houk was extremely unpopular with the local Calabresi.) During Racco's trial, Agent Dimaio and District Attorney Young noted the presence in Hillsville of a number of underworld assassins from Ohio and New York State. They believed the gunmen were in town to intimidate witnesses against Racco.

It seems, however, that the local Calabrian outfit actually was uninterested in discouraging testimony. Racco's conviction was secured largely on the basis of witness statements by his old underworld associates. Agent Dimaio later boasted that his expert handling of the witnesses resulted in their cooperation with law enforcement. He neglected the possibility that they testified merely to inflict upon Racco the punishment he earlier avoided at the hands of the underworld tribunal.

While Racco pursued his legal appeals, newspapers discussed the apparent ease with which he raised a defense fund. They speculated that, while deposed as chief of the Hillsville Society, he retained membership in a national organization headquartered in New York City and was receiving financial assistance through that group. Though well-financed, the appeals were unsuccessful. On October 26, 1909, maintaining his innocence of the murder charge and refusing to provide any evidence against his old underworld comrades, Racco was hanged to death at the Lawrence County Courthouse.

News reports from that period referred to Racco's broad support network as "Camorra" and "Mafia." These terms, along with the often used "Black Hand," appear to have been employed in a general sense to refer to an Italian organized criminal entity. It seems unlikely that the Calabresi had merged with either Neapolitan or Sicilian crime networks by this early date and no Neapolitan or Sicilian criminals figured prominently in the Racco story. In his autobiography, Nick Gentile noted that he was part of the Mafia of western Pennsylvania at the dawn of the Prohibition Era - more than a decade later - and that consolidation of Sicilian, Calabrian and Neapolitan criminal groups was just occurring in the region at that time.

During the course of Dimaio's investigation, one of his undercover men became acquainted with a highly regarded Racco gang member known as John Jatti (his actual surname may have been something closer to "Giotti"). Jatti was renowned for his proficiency with a blade and provided instruction for other gang members in the deadly use of the stiletto. It was said that Jatti, a native of the Calabrian town of Santo Stefano, had been a student of Giuseppe Musolino, the Calabrian "Robin Hood."

Giuseppe Musolino

Judicial corruption and the false testimony of enemies resulted in Musolino, also from Santo Stefano, being jailed in 1897 for a crime he did not commit. At the moment of his conviction, as his sweetheart reportedly died of her shock and despair, Musolino swore vengeance on all who conspired against him. It seemed an idle threat as Musolino was locked away. But he and a number of other inmates were able to tunnel out of prison, and Musolino set right to work on his vendetta.

(While there is little doubt that Musolino was unjustly railroaded into prison for a crime he did not commit, we should not infer that he was an entirely innocent party. From the obvious rivalry with organized gangsters, his own future actions and the actions of his friends and family members, it appears that Musolino was a member of an outlaw band before 1897.)

Authorities attributed dozens of murders, numerous robberies and enormous property damage to a Musolino rampage that lasted about two years. With the sympathy and support of the local citizenry and apparently a vast army of relatives, the brigand was able repeatedly to elude government pursuit. According to legend, Musolino was finally betrayed by a former lover and an old friend named DiLorenzo, who had fallen for each other and for the sake of their safety wanted Musolino placed permanently behind bars. He was captured by the authorities on October 16, 1901, far north of his Calabrian home territory. The following summer he was sentenced to life in prison.

John Jatti reportedly escaped Italy as government forces moved against Musolino's followers and supporters. He sailed for the U.S. and settled in western Pennsylvania. Other men associated with Musolino also decided to relocate to the U.S. and to Canada.

In the summer of 1911, Canadian authorities stumbled on a Calabrian criminal organization in Toronto while they worked to solve the July murder of Frank "Tarro" Sciarrone. Frank Griro eventually confessed to the killing, but claimed he shot Sciarrone to free himself from the incessant extortion demands of the Calabrian Black Hand Society.

Echoing stories provided by informants from Racco's western Pennsylvania organization, Griro said he was being pressured by Sciarrone to affiliate himself with the Black Handers by providing regular cash payments. Reports indicated that the Black Handers had a two-class structure, with a powerful veteran elite class overseeing and financially benefiting from a large body of underlings who subscribed, willingly or not, to membership. Griro gave police information about the organization, its meeting place and its members.

The leader of the group was said to be Joe Musolino, owner of a restaurant at 165 York Street and cousin to the romantic Italian outlaw Giuseppe Musolino. (The Toronto resident's given name was "Giuseppe," just like his more famous cousin, but we'll call him "Joe" for clarity.) As the brigand Giuseppe Musolino was being cornered in Italy, Joe Musolino moved from his homeland, first to Niagara Falls, New York, and then to Toronto. In a very short time, Joe Musolino established himself as a labor power on the Toronto waterfront and as the leader of a feared group of extortionists.

Police also uncovered evidence that Musolino's Toronto gang had branches in Chicago and Montreal and that it was engaged in the international trafficking of Italian women for use in brothels in the region.

A trial jury accepted Griro's claim of self-defense in the killing of Sciarrone, and he was acquitted of manslaughter. Joe Musolino's growing criminal record resulted in a forced trip back across the Atlantic to his native Italy.

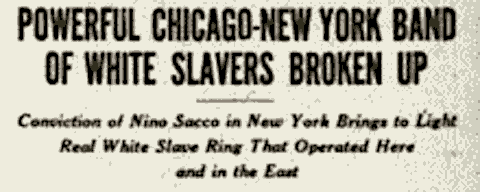

Chicago Day Book, April 15, 1914

A Calabrian crime ring engaged in human trafficking ("white slavery") was uncovered on the U.S. side of the border in the period 1912-1914. (The federal Mann Act, prohibiting the interstate transport of women or girls for immoral purposes, had become law in 1910.) Great public interest in the case was aroused when "The Story of Rosalinda" was published in magazines and newspapers across the country.

Rosalinda Rossi, a young New York woman from an immigrant Italian family, was sexually assaulted May 12, 1912, by Demetrio Marino, a member of the crime ring. Two days later, an apparently remorseful Marino married Rosalinda. But that was merely part of a plan to control the young woman. Marino transported his new bride to Chicago and turned her over to ring member Nino Sacco. For several years, Sacco and his brothers were suspected of importing girls from Italy to serve in Chicago "resorts." Rosalinda was beaten until she agreed to work in a Twenty-First Street brothel managed by a Sacco employee named Madam Jennie Dorno or Jennie Bruno. Rosalinda's family offered money for her return to New York and she was eventually restored to them, though by then afflicted with "the most terrible of all diseases."

As the authorities learned of the abuses suffered by Rosalinda, they raided Sacco's brothel in Chicago and took Madam Jennie and other women found there as witnesses. U.S. attorneys prepared cases against Sacco and Demetrio Marino and also against Frank Filasto, a New Yorker they believed to be the leader of the international human trafficking ring. Though the authorities seemed to be aware of the deperation and brutality of the suspects, their precautions were not entirely sufficient. One of the witnesses in the case, Jennie Cavalieri, was murdered in October 1912, while living in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Filasto was originally from Giuseppe Musolino's hometown of Santo Stefano, and he was said to be another cousin of the famous brigand. Perhaps Filasto was among the crime ring leadership summoned to Hillsville, Pennsylvania, years earlier to judge the charges against Rocco Racco.

Demetrio Marino served several years in New York state prison for his role in the ring. Frank Filasto and a codefendant, James Ribuffo of Paterson, New Jersey, were convicted of Mann Act violations after prosecutors showed that Nino Sacco had sent them postal money order payments for young women shipped to Chicago. Ribuffo was sentenced to two years. Filasto was sentenced to five.

However, Filasto was released under $15,000 bail pending his appeal and promptly disappeared. As authorities noted his apparent escape back to Italy, they revealed suspicion that he had been involved in two dozen murders, including that of Jennie Cavalieri.

Sacco was brought east to New York for trial. He was convicted on April 15, 1914, and sentenced on April 17 to serve two years in Atlanta Federal Prison.

In Chicago, "white slaver" Nino Sacco apparently was associated with vice lord Jim Colosimo. When Collier's Magazine published "The Story of Rosalinda," it revealed that Sacco conducted his business in the cafe and upstairs rooms owned by Colosimo at Twenty-First Street and Armour Street - across from the Dorno-managed brothel. The magazine stated that Sacco was "Colosimo's lieutenant of the vice traffic, being one of the half-dozen active general managers of the white-slave trade in Chicago."

Jim Colosimo

Sacco had some other interesting connections. While in Atlanta Federal Prison, he corresponded with "Diamond Joe" Esposito, Daniel Barone, Joseph D'Andrea and his own siblings Domenico Sacco and Louisa Sacco in Chicago; an uncle Antonio Cagliostro and cousin Thomas Bellantonio in New York City; and a brother Antonio Sacco and cousin James Palese in Buffalo, New York.

Like the Calabrian Colosimo, the Neapolitan Esposito was influential in Chicago's underworld as well as its politics. Barone was an investment broker and a politician. Cagliostro, born in the Calabrian town of Podargoni in 1855, settled in New York in the late 1880s and opened a number of businesses, including a restaurant, a bar and a bank on Mulberry Street, near the Five Points. Little is known of James Palese, but it is curious that the same name turned up years later - this time with a Detroit address - in the papers of the murdered Chicago gangster Orazio Tropea.

Joseph D'Andrea looks to have been part of a hit squad assembled by gangster John Torrio shortly after his move from New York to Chicago. The squad was believed responsible for the murders of three extortionists who had been threatening Jim Colosimo.

Colosimo was a native of Colosimi, a town in the Cosenza province of Calabria. He traveled to the U.S. in 1891 as a boy and settled with paesani in Chicago. About a decade later, he married Victoria Moresco. Generally regarded as a brothel manager before her union with Colosimo, Moresco had family connections in New York City, Chicago and the western U.S. Jim Colosimo took over management of his wife's business and expanded it. He also became an important political figure in the vice district and in the Italian colony of Chicago. For some years, Victoria's brother Joseph served as a top Colosimo aide.

When extortionists began to plague Colosimo, legend says Moresco sent for her New York gangster cousin, John Torrio. (The relationship between Moresco and Torrio remains uncertain, and some say - vaguely and without proof - that Torrio was Jim Colosimo's cousin).

John Torrio

Torrio reportedly was born in Irsina, a town in the southern mainland Italian region of Basilicata, just north of Calabria. His father died when Torrio was a young boy, and Torrio was taken to New York by his mother. Torrio was raised in a Calabrian home on James Street, following his mother's marriage to Salvatore Caputo, a native of the eastern Calabrian city of Zinga. (It seems unlikely that Torrio shared a blood link to Moresco or Colosimo, but he may have been related to one of them through his Calabrian stepfather, Caputo.) Only about one block of James Street exists today, but at the time it was a seven-block road running from Park Row, close to the Five Points, southeastward to the East River.

Among Torrio's James Street neighbors was the family of Giuseppe Vanella, also originally from Basilicata. Vanella's son Rocco "Robert" Vanella (known in criminal circles as "Rox" and "Roxie") was close in age to Torrio and as a youth may have been drawn into the same Jack Sirocco and Chick Tricker-allied street gangs in the Five Points area that attracted Torrio. Some sources say Vanella and Torrio were cousins.

It is generally accepted that Torrio visited Chicago in 1905 and 1907 before relocating there around 1909. In the same period, Vanella also moved west. He was arrested October 13, 1907, in Laurel, Montana, and charged with the shooting murder of his roommate and robbery partner Raffaele Orasio. Newspapers noted that he had many friends in the Chicago area and family back in New York. Vanella was convicted January 25, 1908, of second-degree murder and sentenced to fifty years in the Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge.

A public campaign for a Vanella release or retrial was launched by his mother in New York and by philanthropist Ethel Eppstein of San Francisco. A less public campaign was also helpful to Vanella's cause: The chief witness against him met with a violent end in the railroad town of Taft, Montana, in October 1908. Police suspected that Vanella's underworld friends had eliminated the witness. The combined efforts resulted in Vanella's release on parole in the spring of 1913.

By the summer of 1914, Vanella was again suspected of murder. This time, the killing occurred in Chicago, a law enforcement officer was the victim, and authorities speculated that Torrio, Colosimo and others engaged in the vice trade were also responsible. They theorized that local resort managers contracted with Vanella to eliminate morals inspector W.C. Dannenberg, who was conducting frequent raids in the vice-lord-controlled Levee District. During a chaotic gunfight on July 16, police Sergeant Stanley Birns was shot and killed. Charges were filed against Vanella, Torrio and others, but little resulted from them. Vanella was back in New York the following year.

(It seems this is the same Rocco "Rox" Vanella who established a successful undertaking business on New York's Lower East Side and helped to organize a union of rag pickers and paper sorters. At the time of his 1921 wedding to Sadie Faranda, he was called "Mayor of James Street." John Torrio served as best man at that wedding. There is still a funeral home, Vanella's Funeral Chapel, at the original 29 Madison Street address of Vanella's business. However, Vanella's Funeral Chapel has omitted references to "Rox" from its official business history, focusing instead on "Rox's" little brother Vincenzo as its founder.)

The 1914 incident was not the only time police suspected Torrio of summoning a gunman-friend from New York City for "work" in Chicago. Around 1919, he welcomed young Brooklyn gangster Al Capone into the growing Colosimo-Torrio underworld organization. In May 1920, when a well-placed bullet made the Colosimo-Torrio gang into just the Torrio gang, Brooklyn-Calabrian gangster Frankie Yale happened to be in Chicago. And Yale happened to make another trip to the Windy City about four years later as Torrio rival Dean O'Banion was shot to death.

Frankie Yale provides an example of a gangland boss who bridged the gap between the era of separate Calabrian and Sicilian criminal organizations and the era of Sicilian-Calabrian combination. (Frankie Yale biography)

Frank Yale

Yale was born in 1893 to Domenick and Isabella DeSimone Ioele of Longobucco, a town in the Cosenza province of Calabria. Domenick Ioele crossed the Atlantic in 1898. Within a decade, the rest of his family had joined him in New York. In 1907, Domenick's address was noted as 66 James Street, next door to the Vanella family and just down the block from a saloon, pool room and brothel run by John Torrio.

(When Isabella Ioele arrived with two children in 1907, their original destination was 46 Baxter Street. They were detained as authorities sorted out that Domenico Ioele's address was 65 James Street. Both addresses were within easy reach of the infamous Five Points neighborhood of the Lower East Side.)

Like Torrio's family, the Ioeles relocated to Brooklyn. Domenick ran a produce shop there. As a teenager, Frankie Yale involved himself in various gang activities. At age twenty-three, he was convicted of possession of a loaded revolver without a permit and was sent to Blackwell's Island Penitentiary. Yale's home address in that period was 6605 Fourteenth Avenue in Brooklyn, just around the corner from the family home, 1440 Sixty-sixth Street. At the time of Colosimo's murder in Chicago, Yale was running a funeral home.

Author Daniel Waugh has noted an interesting Yale connection. As early as the summer of 1920, according to Waugh, the name of Mafioso Vincenzo Terranova was associated with the ownership of the Harvard Inn, a popular Yale-run summer cabaret on Coney Island. This suggests cooperation between Sicilian and Calabrian organized criminals in the opening months of Prohibition. The Yale-Terranova connection reported by Waugh, is backed up by two news reports at the time of Vincent Terranova's 1922 murder in East Harlem. The New York Evening Telegram and the New York Evening World reported that Terranova was (or had been) an owner of the Harvard Inn.

As Yale increased in importance in the underworld, a number of attempts were made on his life. He was wounded in a gunfight at Park Row in Manhattan in February 1921. Months later, while traveling home from the Harvard Inn with his lieutenant Anthony Carfano, brother and driver Angelo Ioele and two other men, their automobile was riddled with bullets. Then, Yale driver Frank Forte was shot to death - perhaps by mistake - near the Yale home in the summer of 1923.

Some blood was spilled in this period, 1922 to 1923, in an apparent feud between Calabrian and Sicilian gangsters in Brooklyn. While that may have been a symptom of underworld consolidation, there is little evidence that the attempts on Yale's life were directly linked to it.

Following the 1924 Chicago murder of Dean O'Banion, police in the Windy City arrested Yale and his traveling companion, Sicilian-born Saverio "Sam" Pollaccia (Learn more about Saverio Pollaccia). In addition to his underworld roles, Pollaccia was proprietor of a Coney Island restaurant. During questioning, Yale admitted he was a friend of Al Capone. He claimed he had nothing to do with the O'Banion killing and denied even knowing John Torrio. He said he traveled to Chicago to attend the funeral of recently deceased Mike Merlo, an important leader in the Italian community (according to Gentile, Merlo was a top-level Mafia boss in Chicago), and then extended his stay to attend a dinner arranged for him by Diamond Joe Esposito. This 1924 Yale visit to Chicago clearly puts Sicilian, Neapolitan and Calabrian criminal elements together in an interstate, if not national, association.

In the middle of the 1920s, both Yale and Pollaccia became important allies of Manhattan-based Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria, chief rival of American Mafia boss of bosses Salvatore "Toto" D'Aquila. Pollaccia previously had been D'Aquila's trusted aide, and Yale may have had an earlier association with D'Aquila as well. At about the same time, John Torrio retired from the Chicago underworld and turned his operations over to Al Capone.

Like Calabrian Yale and Sicilian Pollaccia, the Neapolitan Capone became affiliated with a growing and increasingly diverse Masseria alliance. The timing of Capone's combination with Masseria is uncertain, but it must have been around 1927-1928, as Masseria was nearing the pinnacle of his profession then and could project his power into the Chicago underworld. Capone was emerging as the greatest threat to established Sicilian interests in Chicago and benefited from an alliance with the open-minded New York Mafia boss. It seems likely that Masseria increased his strength by welcoming other Neapolitans, including Vito Genovese of New York and New Jersey, into his organization at roughly the same time. (Other Sicilian Mafia bosses were a bit slower to embrace Neapolitans and did so only when increased manpower became necessary to combat Masseria in the Castellammarese War.)

Persistent underworld legend states that, during Prohibition, Yale supplied large quantities of imported alcohol to the organization of his old Brooklyn friend Al Capone. But the legends indicate that there was a falling out between the two over their liquor deals and this coincides very closely with the moment Masseria and Capone cemented their relationship. By 1927, Capone was reportedly so distrustful of Yale that he inserted an ally, James DeAmato, into Yale's Brooklyn gang. Perhaps caught spying for Capone, DeAmato was murdered in the summer of 1927.

A Yale-Capone feud apparently took some time to fully erupt, as Yale is known to have attended the September 1927 Dempsey-Tunney prizefight in Chicago as a guest of Capone. When Yale was shot to death in his automobile in early July of 1928, the authorities immediately suspected that Capone was involved.

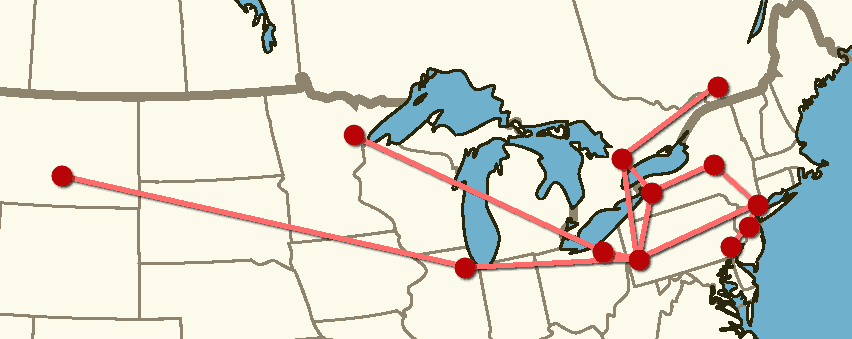

If we accept the legends regarding the Yale-Capone business relationship, we are put in a position of having to explain how Yale, as a fairly young Brooklyn gangster, could have arranged for the international import of vast quantities of illicit alcohol. The Calabresi in Ontario, Canada, and border areas in New York State may provide an answer.

The sale and consumption of alcohol in Ontario had been made illegal in 1916, during Canada's early involvement in the Great War, but a number of breweries and distilleries were permitted to carry on their businesses for the export market. Calabresi in control of the immigrant underworlds in Ontario cities were in a good position to capitalize on the local alcohol black market and to establish protective relationships with corrupt law enforcement officers and politicians. With affiliated Calabrian criminal organizations on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border, they could fairly easily regulate the flow of alcohol across that border.

Ontario's Calabrian gangs were led for a time by Domenic Sciaroni of Guelph, and James Celona and Rocco Perri of Hamilton. ("Sciaroni" looks to be a mere spelling variation of "Sciarrone," suggesting a family relationship with the Musolino lieutenant murdered in Toronto in 1911.) Celona's April 1918 murder put Perri in sole command of Hamilton's Calabrian underworld and on the fast track to becoming "King of the Bootleggers." Perri had spent time in the Ontario communities of St. Catherine's and Toronto, and back in 1910 was known to be friendly with both Joe Musolino and Frank Griro, the killer of Frank Sciarrone. Just across the U.S. border, the Sirianni brothers controlled the Calabrian underworld in Niagara Falls, New York.

Willie Moretti

As murder removed Domenick Sciaroni from the region, another important Calabrian criminal moved in. Guarino "Willie Moore" Moretti, born in East Harlem, New York, to Calabrian parents, spent his younger years in New York City and Philadelphia, but then suddenly relocated to the Buffalo-Niagara Falls area about 1918. Moretti would have been well qualified to serve as a liaison between Calabrian and Sicilian gangsters. He was often in contact with Sicilian Mafiosi in East Harlem. In 1915, he witnessed the shooting of Morello-Terranova gang leader Charles LoMonte at 116th Street and First Avenue and carried the mortally wounded LoMonte across the street to Sydenham Hospital. (Moretti was arrested on a concealed weapon charge after leaving LoMonte at the hospital. He claimed that LoMonte's handgun fell out of his pocket on the way across the street and Moretti picked it up and put it into his own pocket for safekeeping.)

The influential Calabresi in Guelph generally appear to have maintained a distinct underworld identity in this period, and Sciaroni reportedly was uneasy even about having business relationships with the Sicilian Mafia bosses who were growing powerful around him in Toronto, Buffalo and Detroit. On the other hand, Perri seems to have had no qualms about working with the Mafia. And the Calabrian Sirianni brothers and Willie Moretti were similarly cooperative.

It may be a sign of the finalization of an Italian underworld merger that both Sciaroni and his like-minded ally Maurizzio Bocchimuzzo were murdered in the spring of 1922, about the same time as Sicilian-Calabrian violence in Brooklyn. And it may be no coincidence that Calabrian Moretti later recalled the 1922-23 period as the moment he first met Neapolitan Al Capone of Chicago.

Moretti was by then considered a top aide to western New York's new Mafia boss Stefano Magaddino. Magaddino showed personal trust in Moretti and a fair level of regard in his resourcefulness when he dispatched Moretti to Florida in December of 1924 to assist Magaddino relative Joseph Bonanno. The young Bonanno had been arrested at Jacksonville entering the country illegally.

During his stay in the Niagara Falls area Moretti also formed a close long-term friendship with Magaddino lieutenant Paul Palmeri. The friendship continued through Moretti's and later Palmeri's relocations to New Jersey. The two became in-laws when Moretti's daughter and Palmeri's son were wed in New Jersey in 1947.

But Moretti's closest relationship appears to have been with Frank Costello. Born in the Calabrian city of Cosenza, Costello was brought to New York as a small child. He and Moretti reportedly grew up together in East Harlem, and some sources say they were cousins. In the same year, 1915, that Moretti was charged for having a concealed weapon, Costello was convicted of a misdemeanor revolver possession charge.

Frank Costello

Costello was not yet thirty when the Prohibition Era began. A few years after the sale, manufacture and transport of alcohol became illegal in the U.S., Costello faced a federal indictment for leading a rum-running conspiracy. Years later, when questioned by the U.S. Senate's Kefauver Committee about his rum-running days, Costello admitted to arranging for the import of liquor manufactured in Canada. He insisted that he did not personally purchase the liquor or transport it but that "people" did that for him.

(Costello told the Kefauver Committee in 1951 that he was not engaged in rum-running before 1926. The federal charge was filed against him in 1925. He suggested there was no basis to that charge, but all considered it odd that he would first become involved in 1926 with a crime for which he was federally charged in 1925. In testimony before the New York State Liquor Authority in 1947, Costello admitted that he was engaged in importing Canadian liquor from as early as 1923.)

With Calabrian gangsters in control of the flow of liquor across the border in the early years of U.S. Prohibition and Calabrian gangsters like Costello in Manhattan and Frankie Yale in Brooklyn apparently controlling the import of liquor to the New York City area and beyond, we have some good answers for the when and why of Sicilian-Calabrian underworld cooperation. It also is easy to explain how Costello quickly became an important figure in the Masseria Mafia organization.

Frank "Ciccio" Milano was, for a brief time, the most important Calabrian crime boss in the United States. Born in February 1891 in the Calabrian town of San Roberto, a short distance from Santo Stefano, he sailed to the U.S. in 1907. He spent most of the next three decades in northeastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania.

In November of 1912, Frank Milano his brother Anthony were arrested in Duluth, Minnesota, by local detectives and an agent of the Secret Service. The Milanos were found to be in possession of coin-counterfeiting molds and quantities of metals. Authorities determined that Anthony Milano had jumped bail after being charged with counterfeiting in Cleveland two months earlier and had headed west with his brother. Both were tried on counterfeiting charges. Frank Milano was acquitted, but Anthony was convicted and sentenced in January 1913 to six years in Leavenworth Penitentiary.

A half year later, Frank Milano was again in the news. He and an associate whose name was recorded in the press as "Antonio Mossilino" - perhaps yet another member of the Musolino family - faced counterfeiting charges. Witnesses, reportedly terrorized by a Black Hand organization in Cleveland, would not testify against the suspects and they went free.

Frank Milano

Frank Milano seems to have bounced back and forth between Cleveland and Pittsburgh for a number of years and must have frequently passed through the Youngstown, Ohio, corridor. His presence in Pittsburgh was noted in 1918, when a double-murder of Black Hand extortionists was committed in the back room of a Milano-run pool room. He was again found in the Steel City in 1923, when he tried to persuade a Canonsburg witness to change testimony used to convict two Black Hand killers and, a short time later, was picked up by police at a downtown Pittsburgh hotel for questioning about recent bombings.

In between the Pittsburgh sightings, Milano served in the U.S. Army during the Great War, spent a bit of time in Cleveland's Cuyahoga County Jail, became a naturalized U.S. citizen and built up the Mayfield Road Gang in the Little Italy neighborhood clustered around Murray Hill Road and Mayfield Road in Cleveland. While the timing of Milano's induction into the Mafia is uncertain, it appears that he and his Mayfield Road Gang were allies of the Lonardo family when a gangland war erupted with the Porrello clan over a monopoly in corn sugar, a valuable commodity for moonshining operations.

By the end of 1928, the corn sugar war had claimed the lives of local Mafia boss "Big Joe" Lonardo and his brother John, and the next Mafia boss "Black Sam" Todaro. The bloodshed left Joseph Porrello in the position of Cleveland Mafia boss. As Porrello's ally, "Joe the Boss" Masseria, gained control in New York and became U.S. Mafia boss of bosses, there was a brief period of calm before the Castellammarese War began in 1930. During this period, Porrello hosted a national Mafia convention in Cleveland. On July 5, 1930, Joseph Porrello and his lieutenant Sam Tilocco were shot to death in the doorway of Milano's Venetian Restauant on Mayfield Road.

Milano and his gang had grown in strength and influence during Prohibition and were able to brush aside what remained of the Porrello organization. Milano assumed control of the Mafia in Cleveland at a critical moment. Following the 1931 murders of Masseria and his boss of bosses successor Salvatore Maranzano, Mafia leaders across the country decided to dismantle the old boss of bosses system for resolving disputes and create a Commission of top underworld chiefs. The first Commission, according to Gentile, included the bosses of the five New York Mafia families, Al Capone from Chicago and Frank Milano from Cleveland.

As radical a change as incorporation into the American Mafia would have been, it could not have wiped clean the memories of individuals who previously were part of a different underworld society. So, if an association of Calabrian criminals existed before Calabresi were welcomed into the Mafia, we should expect to find evidence of some widespread organizational memory - the old friendly relationships and the old rivalries of the Calabresi as a group should resurface from time to time.

There are some examples of this. John Bazzano's brief tenure as boss of the western Pennsylvania Mafia is one.

John Bazzano

Bazzano, born May 22, 1888, in Palizzi Marina on the southern Calabrian coast, emigrated to the United States as an adult. He settled first in West Virginia, soon relocated to western Pennsylvania and became an American citizen in 1916. He served his adopted homeland in the Great War. Early in the Prohibition Era, Bazzano earned a substantial income through involvement in confection and yeast businesses, which provided essential ingredients for moonshining operations. In 1924, he married Rosina Zappala in New York City.

His bride was a native of Musolino's hometown, Santo Stefano, and she likely was another relative of the famous brigand (her paternal grandmother was Anna Maria Musolino). Rosina also appears to have been related to Calabrian underworld chief and "white slaver" Frank Filasto (her maternal grandmother was Rose Filasto). In addition to New York City, members of the Zappala family resided in the Pittsburgh and New Kensington areas of Pennsylvania and Ontario, Canada. In Pittsburgh, Rosina's brother, attorney Frank Zappala, served as Bazzano's legal counsel.

Bazzano's influence in the Pittsburgh area increased through the years. By the conclusion of the Mafia's Castellammarese War in 1931, Bazzano was the prominent leader of a rival faction to local boss Giuseppe Siragusa, a loyal vassal of Castellammarese War victor Salvatore Maranzano. Maranzano's murder on September 10, 1931, presented an opportunity for Bazzano. Three days later, Siragusa was found shot to death in the basement of his home. Bazzano stepped to the leadership of the Pittsburgh-based Mafia.

On July 29, 1932, John, James and Arthur Volpe were shot to death inside a Bazzano-owned cafe. (This incident was discussed in the January 2011 issue of Informer.) The Volpes were aggressively expanding Neapolitan racketeers in the East End of Pittsburgh. Everyone seemed to know immediately that Bazzano was responsible for the attack. Vito Genovese, second-in-command of the powerful Luciano Crime Family in New York and a leading figure among Neapolitan racketeers in the Mafia, was enraged and blamed several of his underworld colleagues for the murders. Genovese targeted Bazzano and his Calabrian-paesano in Brooklyn, Albert Anastasia, in a vendetta.

Anastasia (see feature article in June 2015 Informer issue) and his brothers, originally from Tropea, in Calabria's Vibo Valentia province, were Brooklyn waterfront racketeers who joined with their Calabrian countrymen the Giustra brothers and other allies to assemble a political and labor monopoly on the docks. Albert Anastasia had strong ties to Calabresi in upstate New York and spent time in Utica. While he worked alongside Sicilian Mafiosi, he appears to have preferred teaming with fellow Calabresi, and his link with the distant Bazzano is evidence of a continuing Calabrian brotherhood long after a merger into the Mafia had taken place.

Only Anastasia's participation in the disciplinary group-stabbing murder of his pal Bazzano convinced Genovese to forgo his revenge (this, as it turned out, also was merely postponed).

Albert Anastasia

Nick Gentile, one of those initially blamed by the enraged Genovese, felt certain that Bazzano would not have undertaken the attack against the Volpes on his own. After a bit of investigation, Gentile concluded that Cleveland boss Frank Milano, the sole Calabrian member of the Mafia's dispute-resolving Commission and a close friend of Bazzano, had given Bazzano the OK. Milano, by that time, was well established in his position and well liked by other bosses. Less than a week before the Volpe killings, he traveled between San Diego, California, and a ranch in Mexico in the company of Mafia leaders Jack Dragna of southern California and Vincent Mangano (Albert Anastasia's boss) and Angelo Caruso of New York. Possibly the group was still together when the Volpes were killed, providing an alibi for Milano. Milano also was known to be well regarded by Dragna and New Yorkers Frank Costello and Charlie Luciano. Perhaps as a penalty for indirect involvement with Bazzano's crime, Milano was quickly replaced on the Commission by Stefano Magaddino of Buffalo. By 1934, Milano left Ohio and settled in Mexico, where he may have been under the protection of his friend Dragna.

The Bazzano-Volpe and Anastasia-Genovese relationships, like the earlier Yale-Capone relationship, provide examples of friction between Calabrians and Neapolitans within the formerly all-Sicilian Mafia. While they are isolated cases, they imply that there was a level of competition between these groups of Mafia newcomers and suggest that group identities survived a Mafia merger.

It is worth noting that a number of gangsters believed to have been close associates of Anastasia also came from Calabria. These included John "Silk Stockings" Giustra, Carmelo Liconti and Vincent "Jimmy" Crisalli. Giustra and Crisalli may have been related to each other, and it appears that Liconti was related to the Zappala family of New York and western Pennsylvania, as his mother's maiden name was Anna Zappala. It is believed that Liconti and Giustra also had been close associates of Frankie Yale.

Giustra and Liconti, partners in a Brooklyn funeral home, appear to have been targeted by rivals immediately after the April 15, 1931, murder of Joe Masseria. Both supposedly were called to Manhattan on May 10, 1931, to resolve a territorial dispute, and they both would have been killed there and then, but Liconti had car trouble and was late to the appointment. The body of Giustra, who had been a key figure in waterfront rackets, was found riddled with bullets. When Liconti learned of Giustra's death, he nervously hid himself from his enemies but did not do an especially good job of it. His corpse was discovered in the Hotel Paramount on July 9. He had been choked and stabbed to death.

At about the same time, Yale's old friend Sam Pollaccia vanished, never to be seen again. Nick Gentile learned that Genovese, satisfying another personal vendetta, had taken Pollaccia to Chicago to be disposed of. On the way, Genovese and Pollaccia passed through Pittsburgh and met with Bazzano (still alive, but not for long). Genovese quietly informed Bazzano of his plans for Pollaccia. The Pittsburgh boss was upset over the Genovese's plan but took no action against the important Neapolitan underworld leader, sealing Pollaccia's fate and ultimately his own.

The press speculated that the murders of Giustra and Liconti and the disappearance of Pollaccia were in some way retribution for the murder of "Joe the Boss" Masseria. The idea makes little sense today, when we know that virtually all of Masseria's underworld allies agreed with and conspired in his assassination. But there is a clue to their cause: Gentile stated the Genovese grudge against Pollaccia stemmed from a personal offense committed years earlier by Pollaccia when he was a close adviser to Masseria. Could it be that Pollaccia advised against a merger with Genovese and the Neapolitans? Were Giustra, Liconti and Pollaccia all murdered as a consequence of lingering rivalries within the Mafia?

(The press actually considered an earlier killing to be a reprisal for the Masseria assassination. It was the April 17, 1931, shotgun slaying of twenty-nine-year-old Brooklyn racketeer Ernest "Hoppy" Rossi. Rossi's murder appears at first glance to be in conflict with a theory relating to the elimination of uncooperative Calabrian gangsters and their allies, because Rossi's family was originally from Naples. However, Rossi was born in the U.S. and grew up at Mott Street and Grand Street addresses on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. His family, like Frank Yale's, moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn. Following his 1931 murder, news reports referred to Rossi as a former Yale gang member.)

A dangerously testy relationship developed between Frank Costello and Vito Genovese. In the 1940s, with Milano pretty much out of the picture, Frank Costello was the preeminent Calabrian Mafioso in the U.S., commanding the former Luciano Family. Willie Moretti at that time served as Costello's top aide. Willie, in turn, relied upon brother Salvatore "Solly Moore" Moretti and Calabrian in-law Peter "Lodi Pete" LaPlaca. A strong supportive relationship also grew between Costello and Anastasia, who by 1951 graduated - due to the disappearance of his boss Mangano - from a top lieutenant into a full-fledged Mafia boss. In his autobiography, Joseph Bonanno noted that it was problematic for leaders in two different crime families to be as closely allied as Costello and Anastasia were.

To outsiders, the Costello-Moretti-Anastasia alliance appeared an exclusive, impenetrable club. That club also had a tendency to get on the nerves of other crime bosses. Moretti, reportedly dealing with the brain deteriorating effects of syphilis, was talking too much and about the wrong things. He spoke openly and cordially when called before the Kefauver Committee, at one point inviting members of the committee to join him at his home. And some Mafiosi feared that Moretti, in unguarded moments, was providing damaging information to other federal investigators. Anastasia, shortly after becoming boss, was in trouble with his peers for reportedly selling Mafia memberships. This was very much in the Calabrian tradition, as practiced by the organizations of Rocco Racco and Joe Musolino, but it was unacceptable to those from the Sicilian Mafia tradition.

Rivals, including Genovese and a number of his Sicilian allies, moved against the trio in the years 1951 to 1957. Willie Moretti and Albert Anastasia were slain in the period, and Frank Costello suffered a non-fatal bullet wound to the head in an attempted assassination.

"Solly Moore" Moretti died in New Jersey State Prison in June of 1952, just before a scheduled parole board hearing. The death of the forty-nine-year-old prisoner was reported to be of natural causes, though no autopsy was performed. Rumors that Solly was murdered while behind bars were so persistent that the state attorney general opened an investigation early in 1954.

Joseph Ida

In Philadelphia, where Moretti had spent some of his early years, his Calabrian countryman Joseph Ida eventually became Mafia boss. Ida and other Philadelphia Calabresi were known to be clannish. True to the pattern, Ida also seems to have had relatives in New York and Ontario, Canada. He initially earned a place in the Philadelphia Mafia because of his bootlegging connections and close friendship with Joseph "Bruno" Dovi. He became boss on the 1946 death of Dovi. Ida attended the Apalachin, New York, Mafia convention three weeks after Anastasia's 1957 murder. He subsequently retired from his leadership role in Philadelphia and moved back to Italy.

The Calabresi in Philadelphia's crime family retained a separate identity even after Ida's departure. Ida's old friend Joseph Rugnetta became the recognized leader of a Calabrian faction and served as consigliere of the crime family. In 1969, the FBI learned that Rugnetta and his faction intended to boycott an induction ceremony of new crime family members planned by boss Angelo "Bruno" Annaloro because it was scheduled for New Jersey rather than within Philadelphia. Bruno contacted Mafia elders in New York City and was advised not to induct members without the active participation of Rugnetta (a Mafia tradition allows an opposing faction to block induction of proposed members for any reason). The ceremony site was moved to Philadelphia to accommodate the Calabresi.

The underworld influence of the Calabresi in western Pennsylvania has been particularly long-lived, beginning with the days of Rocco Racco in Hillsville. Leadership of the Pittsburgh Mafia passed from Calabrian control for a time following the murder of Bazzano. However, Antonio Ripepi, a Calabrian Mafioso who married into the Bazzano family, served in a leadership position in the regional crime family. And Bazzano's son, John Jr., was reputed to be the long-time boss of the organization at the time of his death in 2008.

Clearly there were tightly intertwined families of Calabresi involved in organized crime both before and after incorporation into the American Mafia. Some leaders among the Calabresi appear to bridge from one era into the other.

The beginning of incorporation appears to be the early years of Prohibition, and the motivation for it seems obvious: The Calabresi already were well practiced in smuggling at a time when that became a most profitable skill. The early links, formed in the United States and Ontario, Canada, for the trafficking of women and alcohol (I have avoided delving into substantial Calabrian involvement in drug trafficking), put them in a position to arrange for shipments of Canadian liquor into the United States.

While the Mafia's inclusion of Calabresi may not have occurred at precisely the same moment in every region, it does appear to have been accomplished within a few years of the start of Prohibition in the U.S. It also appears to have predated the absorption of Neapolitan Camorrists.

However, it seems fairly certain that the Mafia did not merely combine with a fully formed Calabrian criminal society. If it had, exclusively Calabrian crime families and Calabrian crime bosses would have been the immediate result. No Calabrian crime families are known to have formed, and it took most of a decade for the first Calabrian Mafia bosses to appear. The examples available to us indicate that leaders among the Calabresi were first welcomed as sub-leaders - under existing Sicilian bosses - of existing crime families.

Such a welcome would have put individuals like Frank Milano, John Bazzano, Frank Costello and Joseph Ida in a convenient position to continue to work with their old underlings, who may have taken on associate status with crime families. The Calabrian leaders would have been able to induct over time other Calabresi as Mafia soldiers, enhancing their own prestige and power. After a short period, but by no means instantly, those individual leaders could make a grab for the role of Mafia boss.

There does seem to be some organizational memory among the Calabresi, hinting at a previous organized crime identity. After becoming part of the Sicilian organization, the Calabresi still tended to gravitate toward each other and to engage in rackets together. They did this even when separated by great distances. They carried on their allegiance to Calabrian paesani and, it seems, also some of their rivalries with others. Further, the practice of selling underworld society memberships repeatedly pops up.

While I don't think we can say for certain that an organized Mafia-like Calabrian criminal society existed in the United States and Canada before it was willingly merged into - or forcibly consumed by - the Mafia, there are some good reasons to consider the possibility. I hope this longer-than-usual column will spark some dialog on the subject.