"[Abraham Zeid] will never 'play the role of stoolie,' no matter what the situation may be, and would rather die than do so. Even if an FBI Agent could tell him when. where and by whom he would be killed, or in other words, the terms of a contract, he would not divulge information in his possession which put the finger on someone else." [1]

- Abraham Zeid described in a 1963 FBI report.

Zeid

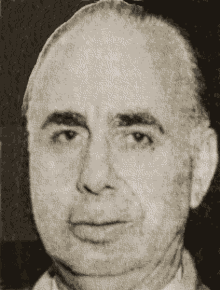

For over forty years, Jewish mobster Abraham "Abe" Zeid navigated the underworld in western Pennsylvania and northeastern Ohio. Closely associated with Pittsburgh Crime Family members Samuel and Gabriel "Kelly" Mannarino, Zeid operated gambling joints, dealt in stolen jewels and handled the organization's dirty work. Law enforcement questioned Zeid in thirty-three murders, including the California murder of Bugsy Siegel. [2]

Zeid's luck ran out on June 24, 1965, when a Pittsburgh jury convicted him and a codefendant for extorting $12,000 from two men over an unpaid gambling debt. [3] Zeid immediately appealed his conviction, so the judge deferred sentencing and allowed him to post bail the same day. [4] He faced a maximum of eleven years in prison and an $8,500 fine.

"I won't serve a day," the fifty-eight-year-old Zeid defiantly told reporters as he was leaving the courthouse.

Zeid and his attorney James Ashton dined at a Pittsburgh restaurant that evening. Afterward, Zeid ended up at Count's Two Worlds, a tavern located at 514 Grant Street. Witnesses said that around 10:45 p.m., he received a phone call at the bar from an unknown caller. Zeid had a brief discussion, hung up the phone, and left the tavern.

Two boys discovered Zeid's body the next day on a farm forty miles away in Claysville, Pennsylvania, near the West Virginia border. He had a gunshot wound behind his right ear. His bruised and battered body showed signs of torture.

Local investigators determined Zeid was heavily in debt and allegedly fell out with the Mannarino organization. However, they did not know that Zeid had jeopardized his life by talking with federal agents and that the secret of Zeid's cooperation might have leaked.

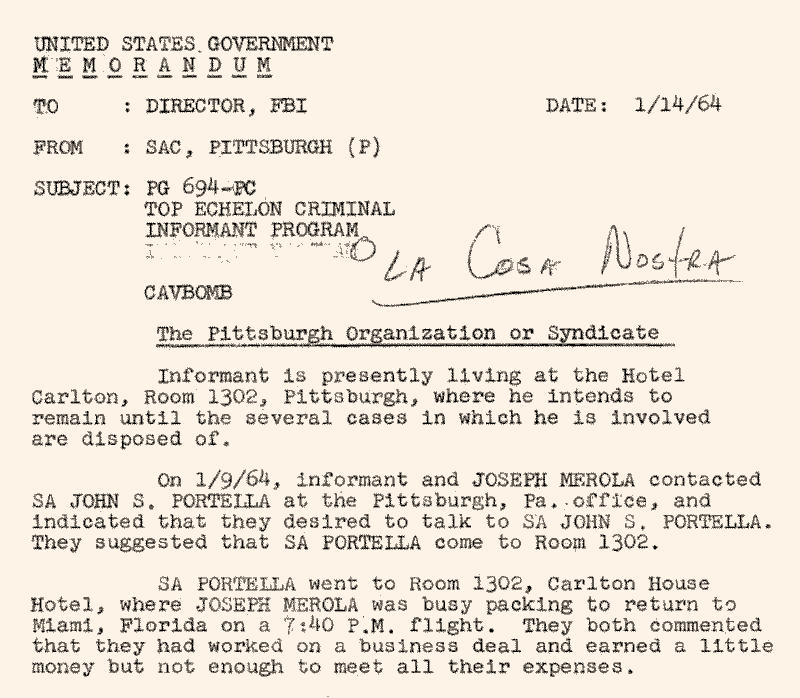

FBI Memorandum, Jan. 14, 1964

Abe Zeid and the informer designated in FBI documents as "PG 694" share many similar identifiers, indicating that they are most likely the same individual:

Zeid

Abraham Zeid was born in Brest-Litovsk, Imperial Russia, on July 30, 1907. [11] (Known today as the city of Brest, it is now part of Belarus, a landlocked country situated between Russia and Poland.) Zeid immigrated to the United States in 1913 with his mother and two brothers, joining his father already in the country. The family settled in Cleveland, Ohio. Zeid was a physically unimposing figure at five feet, six inches, and weighing 150 pounds, but he had a quick temper and good hands. [12]

Smiley

Zeid told federal agents that at the age of sixteen, he became involved in crime, "running 'booze'" during Prohibition. Zeid described himself as a "'soldier' or 'worker' who has faithfully carried out orders given him and as a result of this, he gained a reputation and stature throughout the United States." [13] His underworld aliases were "Al Ross" and "Albert Seid."

First sent to reformatory school as a teenager, Zeid served two significant prison terms in Ohio. He was imprisoned for armed robbery from 1932 to 1935 and from 1938 to 1946. He never applied for American citizenship as a young man, which would cause him problems later in life.

Zeid relocated briefly to California in the late 1940s to work for his brother, who owned two nightclubs and a car dealership in Los Angeles. While living in Los Angeles, Zeid became an acquaintance of Allen Smiley, a Bugsy Siegel associate, which led officials to question him in connection with Siegel's June 1947 murder. [14]

G.Mannarino

As a young man in Ohio, Zeid befriended Frank Valenti, an up-and-coming Mafioso in Pittsburgh. Valenti operated a successful chain of Italian restaurants and later attended the 1957 meeting of top Mafia leaders in Apalachin, New York. Valenti introduced Zeid to the Mannarino brothers and persuaded him to move to Pittsburgh around 1951. [15]

Mafia members Samuel and Kelly Mannarino controlled a criminal empire from their base in New Kensington, Pennsylvania, about twenty miles northeast of Pittsburgh. The brothers answered to John LaRocca, leader of the regional Mafia group. Zeid became a close associate and gained a reputation as a "triggerman for the Mannarino organization." [16]

Zeid described himself as a professional gambler. He bet on horse races and sporting events and operated casinos like the "Red Rock" and Triangle Billiards in partnership with the Mannarino brothers. The casinos allowed patrons to gamble at craps and barbut tables for a $100 limit per play. The casinos reportedly grossed two million dollars a year. Payoffs assured the casinos operated without police interference.

In addition, Zeid performed "arson-for-hire" jobs, torching commercial businesses for insurance fraud. [17] He was also part of a crew of jewel thieves, including Pittsburgh's Joseph Merola and Carl Fiorito from Chicago. They operated primarily in Illinois, Pennsylvania and Florida and robbed homes and businesses for high-priced jewels. [18]

Zeid and his brother-in-law William Kohne turned up at a New Kensington hospital on January 6, 1963. They both were treated for critical gunshot wounds. Zeid had been shot in the abdomen. Kohne was wounded in the thigh. [19]

Parker

Zeid and Kohne told investigators that they were standing in the parking lot of Villela's Motel in the New Kensington suburb of Lower Burrell where Zeid lived, when a gunman in a passing vehicle shot them. Given Zeid's criminal past, investigators initially suspected the shooting was an attempted gangland slaying. The slug removed from Zeid's abdomen was sent to the state's crime lab to be tested.

Investigators became suspicious when they could not find physical evidence of a shooting incident at the motel. Instead, they linked the shooting to an attempted holdup at Parker's Tavern in Pittsburgh's Hill District on the same morning.

Tavern owner Benjamin Parker initially told police that three armed masked men attempted to rob $8,000 from the store safe. A struggle ensued, and Parker, who had a weapon, exchanged gunfire with the robbers, wounding them before they fled. Parker suffered a hand and scalp wound.

The case broke open when the ballistic results from the slug taken from Zeid's abdomen matched Parker's gun. [20] Confronted with test results, Parker altered his story and stated that Zeid and Kohne tried to rob him.

In their hospial beds, Zeid and Kohne were charged with attempted robbery and assault with intent to kill. Police also charged Kohne with unlawful possession of a firearm. Kohne spent two days in the hospital, recovering from his wound, while Zeid's recovery took two weeks. [21] They both posted bail while waiting for the trial to begin.

Kohne

The trial began a year later, on January 20, 1964. [22] Parker testified that a woman named "Sally Harrison," never correctly identified, approached him looking for a job. Later that day, she telephoned him asking to borrow $10. Parker agreed to meet her at his tavern at around 5 a.m. When he opened the back door to invite her inside, Zeid and Kohne rushed through behind her with guns. Parker said he fired at them only after they tried to shoot him. A witness backed up Parker's statements, testifying she saw two males and a female fleeing the tavern after hearing shots.

In the defendants' version of events, Parker was the aggressor. Zeid did not take the stand, but William Kohne testified that he and Zeid were at the tavern playing gin rummy with Parker when a mysterious woman called on him. Parker and the woman went to the tavern's back room by themselves, and Kohne then heard her scream. Kohn said he saw Parker attacking the woman for no reason. Kohne struck Parker to get him off her. Parker then retaliated by shooting Kohne and Zeid. According to Kohne, they returned fire to defend themselves.

The jury accepted the self-defense argument and acquitted Zeid and Kohne of the more serious charges. (It convicted Kohne of the lesser charge of possessing a firearm.) The surprising result led the judge to tell the jury, "I can't understand how you arrived at such a verdict, but you have to live with it." [23]

As Zeid stood before the judge hearing of his acquittal, he harbored a secret. Ten days before the trial started, Zeid reached out to the FBI to talk.

Abe Zeid worked for the Mannarino brothers for over a decade before "bad blood" developed in the early 1960s. It was not one thing that undid the relationship but a series of incidents that put Zeid at loggerheads with the organization.

Pittsburgh Press

While awaiting trial in the Parker's Tavern robbery, the police arrested Zeid for firebombing the Eastgate Plaza shopping mall in Monroeville, Pennsylvania. They also arrested him in two separate forgery cases. [24] The arrests were front-page news, and the Mannarino brothers accused him of bringing too much publicity onto the organization. They began to see him as an unreliable partner.

A turning point came after Zeid began kidnapping hoodlums for quick cash to pay his lawyer's fees. Zeid attempted to shake down a Pittsburgh bookmaker protected by the organization. He threatened the bookmaker with a gun and demanded a $10,000 payment within two days or else.

The bookmaker reported Zeid's ultimatum to Kelly Mannarino, who ordered Zeid to leave him alone. [25] Afterward, Zeid learned the bookmaker paid Mannarino $3,500 to "settle the beef."

Shortly afterward, Zeid approached Kelly Mannarino for a loan, but he was turned "down cold." Zeid was fighting three criminal cases and needed money badly. Zeid admitted to federal agents that he wanted Mannarino "rubbed out." He could have appealed the decision to John La Rocca, Mannarino's superior, but his "pride" prevented him. [26]

Zeid said he had not been very friendly with the Mannarino brothers before asking for the loan, but their refusal to help him was the last straw. He said it "close[d] the door" on their friendship. Zeid now believed that the organization wanted to kill him. As a result, he carried two guns to protect himself, including one in an athletic supporter he always wore whenever he met with them. [27]

Zeid's mounting legal troubles and a deteriorating relationship with his mob superiors eventually led him to seek out the FBI agent targeting him the previous ten years.

Merola

Underworld figures become informers through various routes. Typically, when a mobster decides to cooperate, he contacts the FBI directly or through his lawyer. Limiting the number of individuals aware of his cooperation is essential for his safety. Abe Zeid did something remarkable - he enlisted the help of Joseph Merola, considered Pittsburgh's most hated "snitch."

Joseph Merola and Abe Zeid were old friends. Merola had known Zeid "for many years" and was "familiar with both his personal and criminal past-times." [28] They often worked together in high-profile jewel heists.

Born in 1925 in Pittsburgh, Merola was a smooth-talking racketeer highly regarded by the Mannarino brothers. They used him as a frontman in many of the organization's gambling investments and once introduced him to New York Mafia boss Vito Genovese. [29] Merola was on track to become an inducted Mafia member until he got the organization entangled in a Cuba gunrunning scheme that blew up in their faces.

The Mannarino organization's longstanding gambling interests in Cuba were jeopardized in 1958 when Cuban leader Fulgencio Batista demanded a larger percentage of the profits. To safeguard their investments, the organization decided to back the anti-government forces of Fidel Castro, then fighting a guerrilla war against Batista. Castro reportedly told the Mannarino organization that they could keep their investments if they helped him gain power. Merola responded by organizing an illegal shipment of weapons destined for Castro's forces. In addition, he registered at the United States Department of Justice as a foreign agent of the Anti-Batista forces called the "Revolutionary Civic Front."

Beechcraft plane used in arms smuggling

Hanna, Giordano and Carlucci (left to right)

Merola acquired an arsenal of weapons stolen from the Ohio National Armory in Canton. [30] He and five associates - Stuart Sutor, Daniel Hanna, Joseph Giordano, Norman Rothman, and Victor Carlucci - rented a plane and attempted to ship to Cuba 121 military rifles, including 50-caliber machine guns. [31] All the men were longtime Mannarino associates except for Sutor, who was the pilot. Carlucci was Sam Mannarino's son-in-law.

On November 4, 1958, a loaded cargo plane departed from an airport in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, en route to Cuba. It stopped to refuel in West Virginia, where authorities intercepted it. Law enforcement arrested Merola and his co-conspirators on March 21, 1959, and charged them with transporting stolen military weapons. [32]

A jury convicted Merola and his co-defendants of the charges on February 4, 1960. They were sentenced to five-year prison terms and fines of $10,000. [33] After exhausting their legal appeals, they began serving their sentences on August 25, 1961. [34]

Authorities never charged either Mannarino brother in connection with the scheme. However, after the trial ended, Merola admitted privately to federal agents that Sam Mannarino was involved from the start. [35] Kelly Mannarino reportedly had no part in it and called it his brother's "hare-brained" idea.

Portella

On August 10, 1961, fifteen days before his five-year prison term began, Joseph Merola contacted Special Agent John Portella of the FBI's Pittsburgh office. Merola told Portella that he wanted to speak with him because he had "confidence" in him. [36] Over the next several days, Merola furnished information about the Mannarino organization and numerous thefts and burglaries.

Merola's cooperation remained confidential until February 26, 1962, when he emerged from his prison cell and appeared in a Chicago courtroom as a prosecution witness in a multi-million-dollar fraud case against Sam Mannarino and Norman Rothman. [37] (Rothman was already serving his five-year prison term for gunrunning.)

Merola testified that Mannarino and Rothman, with the help of Canadian Mafiosi, tried to dispose of $11 million of bank bonds stolen in the biggest robbery in banking history. The bonds had been taken in May 1958 from Brockville Trust and Savings Company in Brockville, Ontario. Despite Merola's testimony, a jury acquitted the defendants.

Merola's story took an unexpected turn on November 3, 1962, when federal authorities sprang him from prison. [38] After serving only fifteen months of his five-year prison term in a Federal Correctional Institution at Tallahassee, Florida, President John F. Kennedy issued an order to commute Merola's sentence. [39] Kennedy also ordered the remission of Merola's $10,000 fine (which he had never paid). A law enforcement official stated that he could not recall another presidential pardon in Allegheny County over the last twenty-five years. [40]

Government officials never adequately explained how Merola qualified for the pardon, other than stating he cooperated with U.S. government during the gunrunning trial. However, there were press reports that Merola received the pardon for undercover work in Cuba on behalf of the CIA. [41] Later, the federal government acknowledged that commuting his sentence was an "improvident" error. [42]

Joseph Merola's covert relationship with the FBI began sometime in 1959, after authorities arrested him in the Cuban gunrunning scheme. The FBI assigned him the informant symbol code "MM 660." Merola shared mainly non-confidential information about associates in Miami. The FBI discontinued Merola as a source after his gunrunning conviction in February 1960. However, he contacted the FBI again in August 1961, divulging significantly more confidential information about the organization and agreeing to testify against Sam Mannarino and Norman Rothman.

After Joseph Merola left prison, the Mannarino organization washed its hands of him, labeling him an "outlaw" and a "fink." [43] Sam Mannarino admitted to federal agents that he wanted to kill Merola but held off because he knew the feds would presume he did it.

Carlton Hotel

Abe Zeid remained Merola's friend and business partner, however. Zeid had soured on the Mannarino organization, so Merola's betrayal of the brothers did not put him off. Merola settled in Miami and tried to re-establish himself.

When Zeid decided he wanted to talk with the FBI, he reached out for Merola's help and advice. Unfortunately, the available intelligence reports do not explain why Zeid felt the need to involve Merola in the process or what Merola advised him. Interestingly, the FBI did not note that it was odd or surprising that Zeid used Merola to contact them.

Portella's first meeting notes do not indicate any fear Merola might put Zeid in danger with his criminal associates. It is not inconceivable, then, that the FBI worked out an arrangement with Merola to help them target potential informers, since he reportedly worked with the CIA in a similar unofficial capacity. Furthermore, Merola hated Sam Mannarino and would have done anything to hurt the organization. [44] Alternatively, Zeid might have sought Merola's help after convincing himself that Merola, who had his prison sentence commuted, could help him get out from under legal troubles.

Nonetheless, Zeid might have thought twice about remaining friends with Merola if he knew how his old associate had put a bullseye on his back. When Merola debriefed with federal agents in August 1961, he revealed Zeid played a small part in the gunrunning scheme. [45] (He disclosed the information after the trial, so Zeid was not arrested with the other conspirators.) Merola said Zeid was a "tired old man" in "serious financial straits."

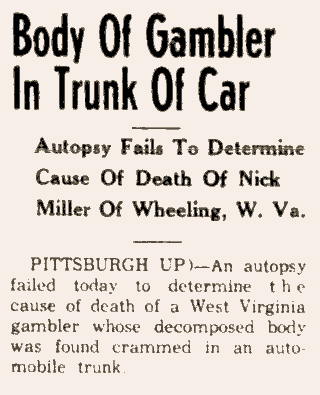

York PA Daily News

More incriminatingly, Merola told the feds that Zeid participated in the murder of West Virginia gambler Nick Miller in August of 1957, in Samuel Mannarino's home. [46] Zeid allegedly held down Miller while the Mannarino brothers strangled him. Zeid later disposed of the body. Miller's decomposed remains were discovered August 22 crammed into the trunk of his automobile.

On January 9, 1964, Merola met Zeid at the Hotel Carlton, where he resided while sorting out his many criminal cases. The twenty-one-story hotel building soared over Sixth Avenue and Grant Street in downtown Pittsburgh. Constructed in 1952, the Hotel Carlton hosted dignitaries and celebrities like Richard Nixon, Nikita Khrushchev and the Rolling Stones before being torn down in 1980.

Merola and Zeid telephoned SA John Portella from the FBI's Pittsburgh Office and stated Zeid "desired to talk." [47] Portella was the same agent Merola debriefed with three years earlier. Born in 1919, Portella joined the FBI in 1941 and served in the FBI's counterintelligence division during World War II. [48] He worked at the Pittsburgh office for more than twenty-three years before retiring in 1976. He was one of their primary organized crime investigators.

Portella met up with them in Zeid's room at the Hotel Carlton the same day. However, Merola did not take part in the discussions with Portella. After greeting Portella, Merola immediately departed to catch a flight to Miami.

Portella had interviewed Zeid several times over the previous ten years, but Zeid always respected the organization's code of silence, never divulging confidential information. [49] [50] However, this time, Portella noted that Zeid was in a "good mood." Zeid advised that he wanted to "straighten out" things he previously refused to discuss. [51]

According to Portella, Zeid was "willing to relate a few of his experiences and some of his knowledge of what he termed 'the Outfit,'" provided his cooperation remained confidential and that the bureau never compelled him to testify.

The intelligence report did not indicate if Zeid received payment for his Intel. [52] It is unclear how frequently Zeid met with federal agents after the initial meeting, but it appears to be a tiny number of times.

Before cooperating, Abe Zeid had several candid interviews with federal agents, which sometimes worked against his interests. For example, Zeid admitted in one meeting that he was not a naturalized American citizen and had not registered himself as an "alien" as required by federal law. The feds turned this information over to the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service, which immediately began deportation proceedings against him based upon his two robbery convictions. [82] The government dropped the deportation order in 1963 when Zeid's birth country refused to accept him. [83]

LaRocca

When Abe Zeid started talking to federal agents in 1964, he was the Pittsburgh organization's most senior figure to furnish confidential Intel about its structure, membership and history. According to Zeid, John LaRocca and Frank Amato were the leaders of the Italian syndicate in the Pittsburgh area, although LaRocca had final authority. Former leader Anthony Ripepi was retired and had little influence, but he still had the bosses' ears. [53] He was allowed to "gracefully retire."

Zeid reported that an early Pittsburgh Mafia leader John Bazzano was killed after he became "overwhelmed with his importance," and ordered the murders of the three Volpe brothers. [54] Bazzano was summoned to New York City to explain the murder of his rivals which had horrified the community.

Bazzano

The gathered leaders of the U.S. Mafia condemned Bazzano to death for his unsanctioned killings of the Volpes. The mobsters pounced on Bazzano at the banquet and stabbed him to death with icepicks. [55]

Following the death of Bazzano, Frank Amato controlled the Pittsburgh Mafia for an extended period and eventually gave way to John LaRocca. (Zeid's chronology omits some bosses.) Zeid described LaRocca as a "peaceful" leader who used violence sparingly. LaRocca frequently prevented members of his organization from taking "hasty drastic action" in favor of a peaceful solution. LaRocca was a popular leader, and Samuel Mannarino later echoed this view. [56]

Zeid stated LaRocca became boss despite "the informant's opposition and the opposition of Frank Valenti." Unfortunately, the available FBI intelligence reports do not provide more context to Zeid's comments. However, one possible explanation is that the organization had an election to determine the next boss after Frank Amato stepped down and LaRocca beat out Valenti.

Valenti

As a result, "bad feelings" developed between the LaRocca supporters and the Valenti faction. Valenti and Zeid were branded "outlaw soldiers" because they initially opposed LaRocca's selection as the boss. In addition, Zeid complained that he and Valenti were forced to live by their "wits" and did not enjoy the same level of success and wealth as other members.

Kelly Mannarino was next in organizational influence. Zeid called Mannarino the "sub-boss." Mannarino's underworld status benefited from marrying Frank Amato's daughter. Zeid said LaRocca, Amato and Kelly Mannarino met regularly to discuss operations, but the times and locations were secret and changed periodically.

Zeid explained that the organization had shelved Sam Mannarino recently and essentially forced him into retirement for unstated reasons. (Other sources stated Sam had irked his superiors by making too many bad decisions.) As a result, Sam's brother Kelly now held total authority over the New Kensington group they once co-managed.

Fontana

Beneath Kelly Mannarino in the hierarchy was a group of mobsters Zeid called "lieutenants." This group included Joseph Sica, Joseph Rosa, Louis Volpe and Michael Genovese. Below them were the "workers" or "soldiers": Frank Valenti, John Fontana, Felix Genovese, Lou Miano and Zeid, himself.

Zeid stated Sonny Ciancutti, who would become boss of the organization decades later, was a close personal friend of Kelly Mannarino but was not a member in 1964.

Zeid referred to the organization as the "Italian syndicate" or "the Outfit." However, he did not use terms like "the Mafia," "the family" or "Cosa Nostra," popularized by informer Joseph Valachi. Nor did he use terminology like "caporegime" or "consigliere."

Zeid stated that the organization prohibited members from involving themselves in drugs and prostitution or stealing another member's wife or money. Use of dynamite was forbidden unless authorized by the leaders. Explosive devices drew too much police attention and could kill innocent people. [57] Several car bombings had recently taken place in the Italian underworld in neighboring Ohio, which the FBI was actively investigating.

Zeid perceived the organization to be primarily a "gambling organization or syndicate" comprised of Italian, Jewish and Irish racketeers. He downplayed the significance of the Italian ethnicity of the organization. According to Zeid, it was not accurate to state, "the Italians have a criminal syndicate known as La Cosa Nostra or the Mafia with the membership exclusively Italian." [58] The primary requirement for membership was "one be engaged in gambling, regardless of nationality."

The Italians were the most powerful faction and maintained their hegemony because "members of their respective families intermarried and this made the bond much tighter." According to Zeid, the organization in western Pennsylvania had always been independent, ruled by one or two persons from the "Pittsburgh area."

Despite being a self-described "soldier," Zeid was Jewish and not eligible to be inducted into the Mafia. Consequently, his understanding of the organization had limits. For example, Zeid mistakenly claimed that Pittsburgh was not part of the nation's criminal organization called the "mob" or the "syndicate" found in cities like New York City or Chicago. [59] Zeid did not seem to fully grasp that the 1957 gathering at Apalachin was a board meeting of Mafia leaders, including his longtime associates John LaRocca, Frank Valenti and Kelly Mannarino. If they told him anything about the meeting, it was not disclosed in the available FBI intelligence reports.

Detroit mobster Joseph Massi was one of the "Mr. Bigs" of the gambling underworld, on a level with Meyer Lansky, the "father of big-time gambling." According to Abe Zeid, Massi allegedly earned $7,500 daily through gambling and casino holdings. In addition, Massi was a rich and generous man, who routinely gave money to strangers and needy associates. [81]

Teemer

According to Abe Zeid, the Mafia never controlled the numbers business in Pittsburgh. The Cleveland Mafia always influenced the Pittsburgh underworld and sent bookmaker Hymie Martin to Pittsburgh in the 1930s to organize gambling rackets. However, Martin could not establish control, so he was replaced by Frank Amato. [60]

Zeid told federal agents that gamblers in Pittsburgh did not need the organization's permission to operate. Any gambler could set up provided they paid police for protection. A notable exception was casino operator Charles Teemer from Chester, West Virginia. Zeid said Teemer kicked up 50 percent of everything he made from his gambling operations to John LaRocca. [61]

Grosso

Zeid said the Mannarino brothers controlled all forms of gambling in the New Kensington area, including betting parlors, casinos and sports betting pools. [62] However, according to Zeid, they had a poor reputation for honoring debts.

The biggest bookmaker in Pittsburgh, Anthony Grosso, had never been under the Mafia's control. According to Zeid, Mafia members often talked about taking over Grosso's gambling operation or becoming his partner. However, LaRocca would not allow an attempt because Grosso had police protection.

Maloney

Grosso made payoffs to Lawrence J. Maloney, an assistant superintendent of the Pittsburgh police department, to operate his gambling enterprise. [63] Grosso also fed Maloney information to arrest any gambling rivals. In addition, Zeid recalled paying Maloney $1,500 a week over two years to operate a casino on the organization's behalf.

Officials indicted Maloney in 1964 for failing to report $230,000 of income received from bookmakers over six years. [64] Grosso testified in court that he paid Maloney $12,000 a year to operate. Although a jury acquitted Maloney of the charges, the police department fired him.

Zeid advised that Jake Lerner was another prominent bookmaker in Pittsburgh. Mafia members John Fontana, Jo Jo Pecora, Mike Genovese, and the Mannarino brothers turned their numbers into Lerner's organization. The Mannarino brothers did not do as much business as they used to, but Lerner paid them a guaranteed $500 commission weekly for the bets they sent him. [65]

Zeid stated the organization had no undisclosed financial interest in Las Vegas casinos and was not receiving secret skim like other crime families. Zeid said his brother Milton worked for the Mannarino brothers in the early 1950s when they controlled the gambling at the Sans Souci Casino in Havana, Cuba. [66] Zeid advised Youngstown mobster Vincent J. De Niro "bank rolled" the Sans Souci Casino. The Mannarino brothers had lost their gambling interests outside of Pittsburgh because of their "lousy" reputation to pay back debts. [67]

For example, Andy Mangini, who operated a gambling club for the organization, was owed $30,000 by the brothers. [68] Mangini was hurting financially after significant gambling losses, but they refused to pay back the debt. Zeid expected Mangini would lose his home as a result. (Sam Mannarino, who had candid conversations with federal agents, said Mangini deserved to die for stealing.) [69]

Abe Zeid said he knew from "personal knowledge" that the Cleveland organization's three leaders were Jack Licavoli, John Scalise and Joseph DiCarlo. Their two "lieutenants" were Anthony DelSanter and Jasper "Fats" Aiello. Zeid said the organization financially supported members serving long prison sentences. Every month, members' wives received payments in return for their husbands keeping their mouths shut.

Because Zeid was a former resident of Cleveland and was familiar with Ohio's underworld, federal agents asked him about several early 1960s car bombings that killed mobsters in the Youngstown, Ohio, area between Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

Zeid stated Youngstown's underworld was not "tightly supervised" by Cleveland or Pittsburgh and was up for "grabs." It had "many separate groups" attempting "to improve their position" in Youngstown, but Cleveland had the final word.

According to Zeid, Fats Aiello controlled Youngstown, located seventy-five miles southeast of Cleveland, because he was married to Licavoli's sister. In addition, Aiello owed the organization roughly $500,000 through his mismanaged barbut gambling operations.

Zeid stated Youngstown's gambling organization was divided between older leaders who made the "big decisions" and the younger hoods who wanted to replace them. Zeid speculated that if friction developed further between the younger and older members, Youngstown could repeat the factional warfare experienced between Joseph Profaci and the Gallo brothers in New York City. [70]

DeNiro

According to Zeid, mobster Vincent De Niro "arranged" for the shotgun murder of independent mobster Sandy Naples on March 11, 1960, after ignoring demands to give the organization a percentage of his rackets. [71] Naples's brother Billy determined that De Niro was behind the killing. According to Zeid, Billy Naples "personally wired up De Niro's automobile which caused his death."

The tit for tat violence escalated when Vince De Niro's brother Louis sought revenge against Billy Naples by placing a bomb under his automobile and blowing him up.

Zeid stated Charles Cavallaro's murder was unrelated to the other recent killings in Youngstown involving De Niro and Naples. [72] A car bomb killed mobster Cavallaro and his 11-year-old son in 1962. Zeid claimed the Cleveland organization ordered Cavallaro's death for testifying before the Kefauver Crime Committee Investigations several years earlier.

Zeid denied underworld rumors that mobster Dominic Moia placed the bomb under Cavallaro's vehicle. The Cleveland organization subsequently eliminated Moia, but Zeid claimed they did it because he squandered their money.

Zeid advised that mobster Billy Lantini operated an unauthorized barbut game in Struthers, Ohio, just southeast of Youngstown. Consequently, the Cleveland organization placed a murder contract on Lantini, and Zeid predicted the organization would kill him sometime in the future.

Despite Abe Zeid's public bravado that he would never spend a night in jail, privately, the guilty verdict left him devastated. Leaving the courtroom after his June 1965 conviction, Zeid fumed at the detective who arrested him in the extortion case the previous October: "You just signed my death warrant." [73]

After discovering Zeid's body, Pittsburgh police tried to retrace his final steps. Investigators surmised he voluntarily got into a vehicle after leaving the tavern, but they could not locate witnesses. They figured a hardened criminal like Zeid, who stated he "trusted no one," would have gotten into a vehicle late at night only with people he knew. Investigators suspected that at least two individuals were involved in Zeid's abduction and murder.

Zeid's body was discovered on his attorney James Ashton's farm in Claysville, Pennsylvania, forty miles southwest of Pittsburgh. Investigators did not publicly speculate on the significance of dumping the body on Ashton's farm. However, an FBI source revealed years later that it was intended to make sure Ashton kept quiet about what Zeid had told him about his illegal activities. [74]

S.Mannarino

The driving time between Pittsburgh and Ashton's farm was approximately seventy-five minutes. Police believed Zeid was killed somewhere other than the farm. The coroner fixed the time of death between 11:30 p.m. and midnight, which was roughly forty-five minutes to seventy-five minutes after Zeid left the tavern.

If those times are accurate, it suggests Zeid got into the killer's vehicle, was taken somewhere and killed all within a little over an hour. His killers then dumped his body at Ashton's farm sometime after midnight.

Federal agents questioned Sam Mannarino in Zeid's murder, but he denied knowing anything about it, insisting he was retired from the rackets. However, Mannarino told agents with typical bluster that he would have killed Zeid himself if he thought it was necessary.

The prevailing view from the Pennsylvania State Police was that "the syndicate" killed Zeid for extorting other "mob members," but they had doubts that they could make an arrest. A police spokesman said, "It's not a mystery of who killed him but as for proving it someday - that's a different matter." [75]

Days after the murder, an unknown FBI source told federal agents that Kelly Mannarino ordered Zeid's murder to show the Pittsburgh underworld that the Mafia was still "strong." [76] Mannarino had tired of Zeid's antics, said the source, and called Zeid a "pest" and a "bother." According to the source, six weeks before his murder, Zeid attempted to shakedown a loanshark under the organization's protection named Joseph Friedman. Mannarino told Zeid to "stay away from Friedman or we are going to get rid of you." Mafia member John Fontana allegedly handled the murder contract. There were no published reports that Zeid was a suspected FBI informer.

Pittsburgh Post Gazette

Whoever killed Abe Zeid apparently tortured him before his death. Zeid's shinbones were shattered, and there were rope burns on his neck, as if a noose had been used on him. [77]

Flex

The manner of Zeid's death could point to the motive for his murder. The evident injuries could have been expressions of his killers' anger with him for some past misdeeds. Alternatively, Zeid possibly suffered the injuries during a forceful interrogation designed to learn whether he was an informer. Newspaper accounts of the murder did not speculate about the significance of the torture.

An FBI source secretly advised in 1973 that Kelly Mannarino ordered Zeid's murder eight years earlier because Zeid was talking to the FBI. This disclosure was the first time an underworld source alleged that Zeid was an informer. In addition, the source reported that Emido D. Flex, Zeid's co-defendant in the 1965 extortion case, was one of the killers. [78] However, the FBI could not interview Flex about the allegation since he died in 1970 from severe burns suffered in an arson job gone wrong.

What led the organization to think Zeid was talking was left unexplained. Did his defiant statement about not spending a night in prison spook his associates? Or did the organization receive Intel suggesting that Zeid had gone rogue? Only one individual outside Zeid and his FBI handler knew for sure that he was cooperating: Joseph Merola. There is no evidence that Merola divulged Zeid's secret.

The murder investigation went cold almost immediately and stayed cold for decades. Zeid's chief nemeses, the Mannarino brothers, died in the interim. (The FBI did not officially participate in the investigation, and it is unlikely they shared Zeid's informant status with other law enforcement agencies.)

A break occurred in 1989, when authorities charged West Virginia racketeer Paul Hankish with running a massive drug and gambling operation covering West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania. Authorities also charged Hankish with ordering Zeid's murder as part of the conspiracy.

An underworld informant alleged that Hankish hired a hit man to kill Zeid, fearing he was a police informant and would give evidence against him in an arson-for-hire case. [79] Zeid was reportedly lured from the tavern by a promise of a burglary score. [80] Hankish was not tried for Zeid's killing. The district attorney dropped that charge after Hankish agreed to plead guilty to drug and gambling conspiracy charges and accepted a lengthy prison sentence.

Abe Zeid's murder remains officially unsolved. He is buried as "Albert Seid" at Pittsburgh's Beth Abraham Cemetery.

1 FBI, Mike Genovese, Pittsburgh Office, Sept. 17, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10284-10042, p. 10.

2 "Probe widens in execution of Abe Zeid," Pittsburgh Press, June 27, 1965.

3 "No Flex threat, victims admit," Pittsburgh Press, Feb. 7, 1968. Zeid allegedly threatened to plant them in a "sewer" if they did not pay. Instead, they ran to the police.

4 "Convicted of blackmail," Latrobe Bulletin, June 25, 1965.

5 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213, p. 2.

6 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, April 21, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10257.

7 FBI, Bombing Murder of Charles Cavallaro, Cleveland Office, Sept. 9, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10492.

8 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, April 21, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10257.

9 FBI, Abraham Zeid, Pittsburgh Office, February 27, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90110-10035.

10 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213; "Zeid silenced by death on mob's order," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 12, 1965.

11 FBI, Samuel & Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Dec. 29, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10452; "Albert Seid," Find A Grave, findagrave.com, accessed Dec. 2, 2021. Zeid's gravestone gave a birth year in 1906.

12 FBI, General Investigative Intelligence Report, Pittsburgh Office, Nov. 2, 1951, NARA Record No. 124-10296-10110.

13 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

14 FBI, Samuel & Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Dec. 11, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10449.

15 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213; FBI, Abraham Zeid, Pittsburgh Office, February 27, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90110-10035. Zeid met the Mannarino brothers in the 1930s.

16 FBI, Samuel & Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Aug. 12, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10039.

17 FBI, Sebastian John LaRocca, Pittsburgh Office, Jan. 2, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-90103-10045.

18 FBI, Samuel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Sept. 15, 1960, NARA Record No. 124-10216-10409.

19 "Mystery girl sought in shootings," Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 8, 1963.

20 "Police say Zeid shot in holdup," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 10, 1963.

21 "N. Kensington gambling aired by 'inside' T-man," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Feb. 20, 1963.

22 "2 on trial for Hill cafe holdup," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 21, 1964.

23 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Pittsburgh Office, July 10, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10241.

24 "Wiretaps give U.S. agents new line on district mob," Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 12, 1971; "Zeid silenced by death on mob's order," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 12, 1965.

25 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, April 21, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10257.

26 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Aug. 5, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10255.

27 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, April 21, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10257.

28 FBI, Abraham Zeid, Pittsburgh Office, February 27, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90110-10035.

29 FBI, Joseph Raymond Merola, Pittsburg Office, Aug. 23, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10203-10491.

30 FBI, Joseph Patrick Merola, Miami Office, June 29, 1959, NARA Record No. 124-90101-10070. Thieves stole 314 military weapons from the armory on Oct. 14, 1958.

31 "Link between Mafia, Castro drew scrutiny to 2 New Kensington racketeers in JFK investigation," Triblive, Nov. 16, 2013. Merola boasted of making several weapons shipments to Cuba before getting caught.

32 "Six indicted in Cuba gun running plot," Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, March 21, 1959; "2 judges named in '59 gun-run-case suit," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Feb 16, 1977. The Batista government in Cuba took note of the gun-running incident and complained to U.S. officials. Viewing the Castro rebellion as an internal Cuban matter, the Eisenhower Administration earlier had halted U.S. shipments of arms to Batista. The episode likely triggered friction and embarrassment within the U.S. underworld, as the major syndicate investors in Havana gambling were supporting Batista in his struggle against Castro.

33 "Six found guilty in Cuba gunlift by jury here," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Feb. 5, 1960; "2 judges named in '59 gun-run-case suit," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Feb 16, 1977. Giordano was sentenced to a three-year prison term and received no fine.

34 "Merola release adds mystery to gun plot," Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 6, 1963.

35 FBI, Joseph Raymond Merola, Pittsburg Office, Aug. 23, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10203-10491.

36 FBI, Gabriel & Samuel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Aug. 11, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10283-10142; FBI, Gabriel & Samuel Mannarino, T.J. McAndrews to C.A. Evans, Aug. 14, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10283-10141.

37 "Mannarino, Canada crime chief linked," Pittsburgh Press, Feb. 26, 1962.

38 "JFK frees gunrunner who was convicted here," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 8, 1963.

39 "U.S. sticks to guns in smuggling case," Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 2, 1977; "Gun-runner upset by convict tag," Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 8, 1963.

40 "Merola release adds mystery to gun plot," Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 6, 1963.

41 "JFK frees gunrunner who was convicted here," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 8, 1963; "Gun-runner upset by convict tag," Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 8, 1963. After his release from federal prison, Merola claimed he helped the American government plan the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in August 1961. The CIA reportedly wanted to exploit Merola's relationships with South American government officials.

42 "U.S. sticks to guns in smuggling case," Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 2, 1977. Other co-defendants tried to use the fact that Merola was a government informer, secretly working against their interests, to get their convictions tossed. Prosecutors contended Merola never provided any information against his co-defendants.

43 FBI, Alleged Attempt on the Life of Joseph Merola, Miami Office, April 8, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90110-10047.

44 FBI, Stuart Sutor, et al., Pittsburgh Office, March 30, 1959, NARA Record No. 124-90100-10137.

45 FBI, Joseph Raymond Merola, Pittsburg Office, Aug. 23, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10203-10491.

46 FBI, Joseph Raymond Merola, Pittsburg Office, Aug. 23, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10203-10491; FBI, Samuel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Oct. 26, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10283-10181.

47 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

48 "Obituaries: John S. Portella," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 1, 1987.

49 FBI, Alleged Attempt on the Life of Joseph Merola, Miami Office, April 8, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90110-10047. Portella interviewed Zeid at the Carlton House coffee shop on March 13, 1963, while Zeid was recovering from the shooting incident at Parker's Tavern. According to Portella, Zeid "gave the appearance of an individual who was awakening to the realization that his whole world was crumbling down upon him and stated all he wants out of life from now on is to be left alone by everyone and to be permitted to live the rest of his days in peace."

50 FBI, Samuel & Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Dec. 29, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10452.

51 FBI, CAVBOMB, Cleveland Office, Feb. 7, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10286-10299.

52 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

53 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Pittsburgh Office, July 10, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10241.

54 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

55 "Bazzano, John (1889-1932)," The American Mafia Who Was Who, mob-who.blogspot.com; "A test of resolve," Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement, February 2011. Zeid omitted much of the incident's backstory, likely because he did not know it. However, the Neapolitan-born Volpe brothers had the backing of Neapolitan mobster Vito Genovese, the number two man in the Mafia organization headed by Charles "Lucky" Luciano. The Volpe murders threatened to upset the Italian underworld's delicate balance between Sicilian and Neapolitan factions.

56 Edmond Valin, "Retired big shot provided FBI with glimpse inside Pittsburgh Mafia," Rat Trap, March 2018.

57 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

58 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

59 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Pittsburgh Office, July 10, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10241.

60 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Pittsburgh Office, July 10, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10241.

61 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Pittsburgh Office, July 10, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10241. Teemer, a longtime Mannarino associate, had led the group of underworld-financed investors who took control of the Havana Sans Souci Casino in 1950. The group included Norman Rothman. The venture was a costly one, and the FBI learned that Pittsburgh interests in Sans Souci were sold a few years later, with Tampa Mafia boss Santo Trafficante acquiring a 60 percent share.

62 FBI, Samuel & Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Dec. 11, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10449.

63 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

64 "Pittsburgh police official indicted in tax evasion," Morning Call, Dec. 19, 1964.

65 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, April 21, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10257.

66 FBI, Samuel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Sept. 15, 1960, NARA Record No. 124-10216-10409.

67 FBI, Interests of Pittsburgh Area Hoodlum Element in Nevada Gambling Industry, Las Vegas Office, Aug. 12, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-90032-10067.

68 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, April 21, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10219-10257.

69 FBI, Samuel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, March 21, 1966, NARA Record No. 124-10284-10051.

70 FBI, Bombing Murder of Charles Cavallaro, Cleveland Office, Sept. 9, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10492.

71 FBI, CAVBOMB, Cleveland Office, Feb. 7, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10286-10299.

72 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

73 "Mild-mannered lawman," North Hill News-Record, April 9, 1975.

74 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Jan. 29, 1974, NARA Record No. 124-10222-10198.

75 "Zeid's slaying a 'mob' puzzle," Pittsburgh Press, June 25, 1966.

76 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Dec. 9, 1971, NARA Record No. 124-10222-10205.

77 "Zeid's slaying a 'mob' puzzle," Pittsburgh Press, June 25, 1966.

78 FBI, Gabriel Mannarino, Jan. 29, 1974, NARA Record No. 124-10222-10198. Zeid's codefendant Emido Flex successfully appealed his June 1965 conviction and won a new trial. In February 1968, a jury acquitted him of all charges except a concealed weapon (switchblade knife) charge. He was sentenced to one year's probation. Flex died at Mercy Hospital on Nov. 16, 1970, after suffering second and third degree burns over 30 percent of his body in an Oct. 11, 1970, fire. ("Probation ends 4 years of trials," Pittsburgh Press, May 29, 1969, p. 6; "Second death in club fire," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Nov. 17, 1970, p. 20.)

79 "New Alexandria man is indicted," Latrobe Bulletin, July 13, 1974.

80 "U.S. says Rooney bet with racketeer," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 19, 1990; "Key figures linked to Paul N. Hankish," Pittsburgh Press, July 19, 1990.

81 FBI, PG 694-PC, Pittsburgh Office, January 14, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10287-10213.

82 FBI, Samuel & Gabriel Mannarino, Pittsburgh Office, Aug. 12, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10039.

83 "Convicted only hours previously," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 26, 1965.