"During the early 1950s, two FBI agents caught a made guy in mid crime. They behaved like gentlemen, so he relaxed and started to tell them war stories - Mafia war stories. They were astonished at his recitation of the table of organization in criminal circles. They wrote it all down and filed the reports in New York. None of the brass believed a word of it; after all, the Director had announced that organized crime didn't exist. Nevertheless, the material was forwarded to Washington. Apparently nobody there believed it either; it was filed and forgotten." [1]

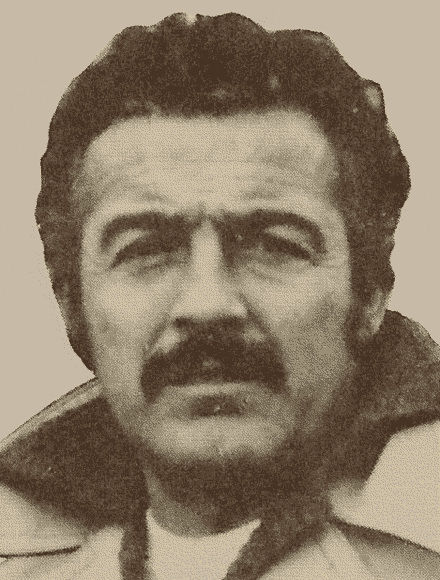

Special Agent Anthony Villano

Extraordinary information regarding an early Mafia informer for the Federal Bureau of Investigation came to light in the memoir of former Special Agent Anthony Villano. Published in 1977, Villano's Brick Agent: Inside the Mafia for the FBI was a no-holds-barred account of his experiences investigating New York City organized crime during the 1960s.

Villano revealed that the Bureau developed a confidential informer (CI) inside the Lucchese Crime Family years before Joseph Valachi cooperated. However, Villano never disclosed the CI's name, referring to him using the alias "Rico Conte." According to Villano, it was Conte "who ... had spelled out the operations of organized crime to special agents, but whom, under [former FBI Director J. Edgar] Hoover's spell, nobody had believed." [2]

Villano wrote that he became "obsessed" with making Conte a source again after the FBI had gone nearly ten years without contacting him. Villano successfully reactivated him in 1966 after he got out of prison. Villano called Conte the "most complete warehouse of material on La Cosa Nostra" that he had ever developed, who had a "gift" for remembering conversations, dates and faces. [3]

Brick Agent provided clues to Rico Conte's identity but left enough ambiguity in the description that identification was hopeless. To this day, Conte's identity remains a government secret. However, Villano didn't anticipate that one day the FBI would declassify the intelligence reports he wrote about his contacts with Conte.

Combining clues in Villano's memoir with those found in the intelligence reports, we can finally unravel the mystery of the FBI's first Mafia informant.

The FBI assigns an informant symbol number to every CI. When an agent writes an intelligence report about his contact with a CI, the agent uses the symbol number rather than a name to keep the CI's identity secret. In the case of the most significant CIs, the FBI continues to mask their identities even after their deaths.

While investigating an organization as massive as the Mafia, federal agents question numerous people. Many become ongoing sources of information. As a result, intelligence reports are filled with countless symbol numbers representing secret informers as varied as doormen, girlfriends, business and criminal associates, and sometimes Mafia members. These individuals never testify in court, and the FBI never publicizes their cooperation.

Villano indicated that the number of Mafia members secretly cooperating nationwide in the 1960s was less than a dozen. "Rico Conte" was one of them.

Reviewing publicly available intelligence reports related to the FBI's investigation into the Mafia shows that Special Agent Anthony Villano developed a Lucchese Crime Family member source in 1966. The FBI assigned the symbol number "NY 1839" to that source. Five details associated in intelligence reports with "NY 1839" correspond to the man Villano called "Rico Conte," indicating they are the same person: [4]

Accepting a link between Conte and "NY 1839" opens up a more detailed profile of the CI compiled using clues attributed to one or the other. For example, Villano wrote in Brick Agent that Conte was incarcerated with Vito Genovese, while FBI intelligence reports indicate that "NY 1839" was incarcerated with Johnny Roselli. Combining those details reveals that the CI must have a prison record overlapping Genovese and Roselli.

Merging Villano's memoir with FBI intelligence reports involving Intel furnished by "NY 1839" reveals the following additional clues about the CI:

After reviewing all the clues and comparing the profile against known or suspected Lucchese Crime Family members, the portrait matches only one known mobster.

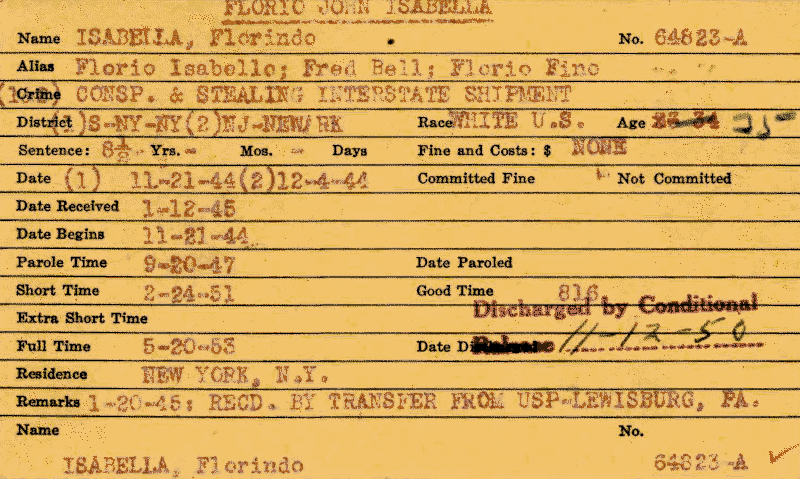

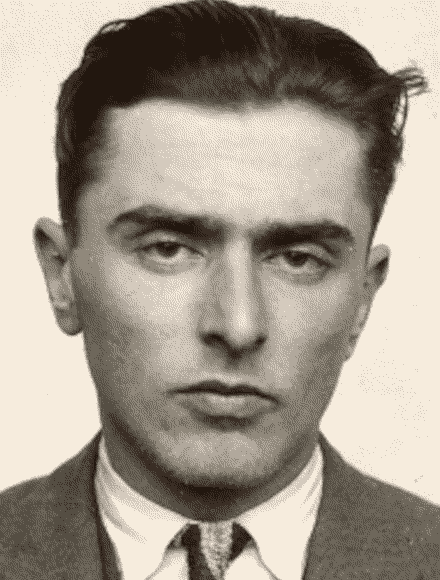

Florio Isabella

Florindo "Florio" John Isabella was born in New York City on March 30, 1911. Named after his grandfather, Isabella grew up on Mott Street in Manhattan's Little Italy. [5] The area was home to tens of thousands of Italian-Americans living in cramped apartments on its narrow streets.

His Italian-born parents were Joseph Angelo and Elizabeth Fino Isabella. After Joseph died, Elizabeth married Gaetano "Tommy the Bull" Pennachio, a former associate of Salvatore (Charles "Lucky" Luciano) Lucania.

It's no exaggeration to say that Florio Isabella grew up in the heroin business. [6] His father Joseph reportedly dealt heroin from the family's small apartment. Joseph allegedly prepared the heroin into small packets at the kitchen table with the help of his mother and brother. They avoided ill effects of the heroin dust by stuffing cotton swabs in their noses. Joseph got his young son Florio to deliver the heroin to customers throughout Little Italy.

U.S. narcotics regulation began in earnest with the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 (effective the following year). However, doctors and pharmacists legally dispensed heroin for medicinal use until it was entirely prohibited in 1924. Those already addicted to heroin were then forced to get their fixes from street dealers like Isabella's father. [7] Italian hoodlums assumed control of the illegal importation and distribution of heroin through a network of national and international alliances. Joseph Isabella eventually exited the heroin business to open a dress shop. But his son Florio became a significant heroin trafficker. This criminal career caused him to spend a total of more than twenty years in prison.

However, Florio Isabella's first prison stay - a four-year term - was the result of a 1930 counterfeiting conviction. While still a young man, he also served two terms of two years for narcotics trafficking in Boston and New York.

Heroin trafficking was a lucrative enterprise. Many hoodlums of the period considered the risk of apprehension worthwhile, since a pre-1980s conviction, even when caught with large quantities of heroin, carried a relatively light prison sentence.

Florio Isabella became a well-known figure to federal law enforcement through his heroin dealing, but a daring robbery made his underworld reputation. In 1942, New Jersey experienced a wave of hijackings of whiskey delivery trucks. Drivers were held at gunpoint and blindfolded while a gang made off with the load. It was estimated the Hijackers stole over $50,000 worth of whiskey. [8] Local law enforcement had no idea who was responsible.

Law enforcement later determined that Florio Isabella and Anthony Colonna headed the gang. Colonna, known as "Jimmy Valentine," was the brains of the operation while Isabella provided the muscle. While certainly a career criminal at this point, Isabella claimed on census records that he was a clothing salesman. Colonna had a criminal record dating to 1909, including a manslaughter conviction.

The gang made a mistake when it hijacked a whiskey truck on the Hoboken Ferry. The robbery in broad daylight in front of dozens of onlookers shocked the city. But the interstate element of the crime drew the FBI's attention.

"He was a kind of gentleman. During a hijacking, Conte noticed the discomfort of the driver, who was bound and blindfolded while the truck was being unloaded at a drop. 'I hate to see you suffering like this,' Conte said to the driver. 'I'll take the ropes and blindfold off if you'll keep your mouth shut later.' [9]

"'I won't identify anyone,' promised the driver, who was, as in so many of these incidents, a knock-around guy himself. Everyone got along so famously that the driver even asked if he might be dropped off near his home to avoid any inconvenience. Conte obliged and even invited him to return to the drop in a day or so and have a case of Scotch on the house."

New Jersery Courier News, Oct. 27, 1942.

The Hoboken Ferry was a boat service used primarily to shuttle freight and commercial vehicles across the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York. Most traffic used bridges and tunnels connecting the two states. The trucks on the ferry parked through the ten-minute crossing, making them easy targets for hijackers to commandeer.

On August 3, 1942, Isabella and an accomplice discreetly boarded the crowded ferry in Hoboken, New Jersey. As the ferry pulled into Manhattan's Twenty-third Street slip, Isabella and his accomplice drew revolvers and jumped into a truck. The truck was loaded with 495 cases of Scotch whiskey from a New Jersey warehouse destined for businesses in New York.

At gunpoint, Isabella ordered the driver and his helper to lie facedown on the vehicle's floor while he taped their eyes shut. He then drove the truck off the ferry to the drop site at a nearby apartment building, where the rest of the gang met them. Isabella held the blindfolded driver and helper captive on the building rooftop while his crew unloaded the whiskey. Afterward, he freed the drivers unharmed.

Isabella recounted years later that he supplied the kidnapped truckers sandwiches while they waited. One of them asked for a cut of the heist since the score was worth $12,000. Isabella, who had taken the names and addresses of the truckers to ensure their cooperation, later mailed him $50 for his trouble. [10]

Because the robbery occurred in waters between New Jersey and New York, the FBI took over the investigation. The gang initially got away with it. However, the gang's luck ran out when one got arrested on a separate charge and rolled over on the others. The FBI quickly detained twelve out of the thirteen gang members. Only Isabella escaped capture.

Colonna was convicted for his hijacking role and sentenced to fifteen years in federal prison. [11] Other gang members, including William Rupoli, brother of hoodlum Ernest Rupolo (though they spelled their surnames differently,) were sentenced to lesser terms.

Federal agents searched for Isabella for the next two years until a showgirl led them to his door.

"...Conte had a marvellous reputation as a lover. He had lived off and on with a variety of showgirls, including some smashers whose names had gone up in lights." [12]

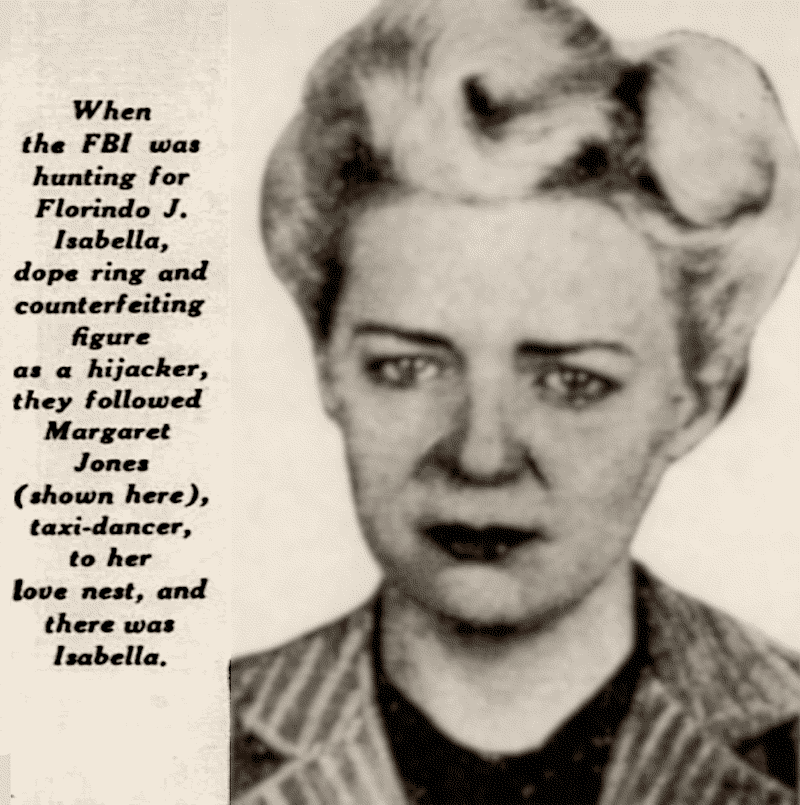

Margaret Jones

Margaret Jones was an attractive blonde with a weakness for dangerous men. Most people called her Marcia or Marsha. [13] She grew up in Manhattan, the daughter of John and Florence Jones. [14] Her father, a musician, died in 1927 at the of 39.

Jones worked as a beautician at a cosmetic factory, but by 1944, the twenty-five-year-old was earning $50 a week as a taxi dancer in a Times Square dance hall. [15] Men paid her ten cents a song to dance with them. Taxi dancers were trendy in the 1920s and 30s but declined in popularity after World War II.

Failing to locate Florio Isabella in any of his old haunts on the Lower East Side, federal agents expanded their search. They were concerned he would form a new gang to commit more robberies. The blue-eyed Isabella was a handsome man with a full head of hair who enjoyed the nightlife and was a regular at nightspots like the Copacabana. Looking into his background, agents determined that Jones was his number-one girl.

The FBI dispatched an undercover agent to pose as a lovesick suitor and dance with Jones every night for a week, hoping she might inadvertently drop a hint about Isabella's whereabouts. But Jones didn't slip up. Agents even tracked her mail, hoping Isabella might contact her, but that was a dead end.

Finally, agents staked out her Manhattan apartment, hoping Isabella might show his face. After weeks of frustration, they spotted Jones leaving her apartment on her day off. They noticed she had dolled herself more elaborately than usual for a Sunday morning. They followed Jones as she made the long trip on public transpiration to Middle Village, a residential neighborhood in Queens. Agents spotted her entering a two-story house on a quiet street.

After a few hours, Jones emerged from the residence in the company of a man wearing dark glasses and a mustache, known in the neighborhood as William Bianco. Isabella didn't wear glasses or sport a mustache, but agents still moved in to question the man. Finally, after two years of searching, Isabella, the last gang member at large, was found. He gave himself up without a fight.

Isabella, described by the prosecutor as the gang's "very, very tough" leader, pleaded guilty to interstate hijacking. [16] A federal judge sentenced him to eight and half years in the Atlanta penitentiary. The prosecutor called the driver to whom Isabella gave $50 to testify at the trial. However, the driver reportedly perjured himself in court rather than point the finger at Isabella. [17]

Isabella entered Atlanta Prison in 1945.

"I remember Rico's smile when I handed him one picture. 'See that greaseball [a nonderogatory term applied to old-timers, like a moustache Pete]? He was a road hitter,' Rico said. 'This was a guy who if Tony Accardo in Chicago had problem, Tony could call Lucchese. 'I need a favour. I got somebody to hit and he knows everybody I got.' Lucchese would send out this greaseball.'" [18]

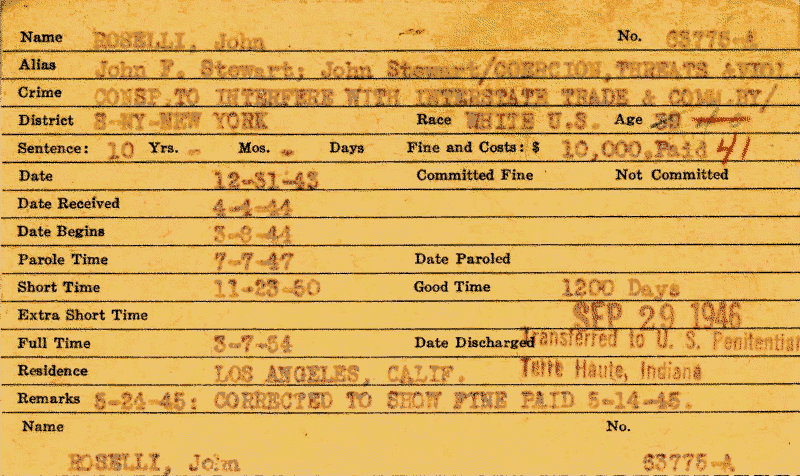

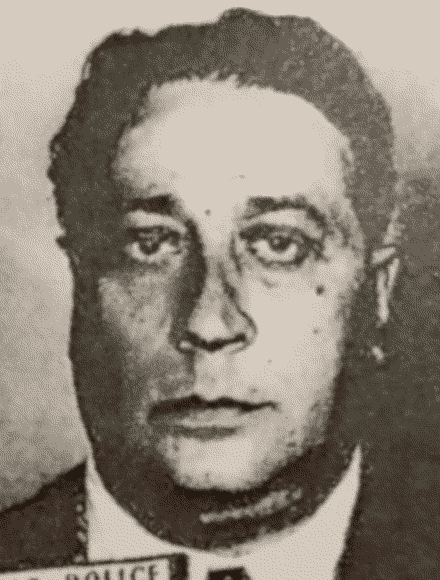

Johnny Roselli

Johnny Roselli was a prominent Mafia member with ties to the Los Angeles and Chicago crime families. Florio Isabella met Roselli in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta after he arrived in January 1945. [19]

Roselli was serving a ten-year sentence for his part in shaking down Hollywood studios. Chicago Outfit leaders Paul Ricca and Frank Nitti, using corrupt union officials Willie Bioff and George Brown, forced studio heads to pay the Mafia millions in secret payoffs to ensure labor peace. The scheme was exposed when Bioff flipped on his associates.

Isabella stated that he and Roselli became "close associates" in prison. Like Isabella, Roselli was handsome and charismatic and always had a pretty lady on his arm.

When Isabella debriefed with Special Agent Villano in 1966, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service was attempting to deport Roselli as a convicted felon. Roselli was born in Italy and had entered the United States as a child, but repeatedly insisted he was a U.S. citizen and failed to register as an alien.

Convicted on a narcotics charge in 1922 in Boston under his birth name of Filippo Sacco, Roselli moved out West to reinvent himself. He adopted the alias of "Johnny Roselli" and created a phony backstory to confound law enforcement. While never more than a soldier, Roselli became an influential underworld figure acting as the Mafia's point man in Hollywood and Las Vegas.

Roselli's decades-long charade was finally upended in 1964 when his good friend Salvatore Piscopo secretly betrayed him to the FBI. [20] The federal government sought Isabella's inside information to build its legal case to deport Roselli.

Isabella spent three years living in close quarters with Roselli but learned nothing that undermined him. Roselli dissembled even with close friends, mixing fact and fiction. Isabella advised that the only name he knew him by was "Roselli." Roselli lied to Isabella, telling him he was born in Chicago and had an uncle in the Mafia. Though Roselli truthfully admitted he spent his early years in Boston and his sister still lived there.

Roselli told Isabella that he lived in Chicago before he moved to Los Angeles. During his "early association with the Capone mob," Roselli boasted that he traveled the country as a "loan-out hit man" - the same story "Rico Conte" told Villano.

According to Isabella, Roselli knew every major hoodlum in the United States, including New York bosses Frank Costello, Vito Genovese and Thomas Lucchese. In addition, Roselli was friendly with Costello's New Jersey lieutenant Willie Moretti. Isabella said Moretti was the "Eastern representative for the Ricca family and Roselli's contact man."

Moretti developed a reputation for speaking candidly about his criminal activities, including his friendship with Roselli, which upset his mob associates. Roselli accused Moretti of "blowing his top." Moretti's indiscretions hurt Roselli's chances of securing early parole. Mafia bosses eventually ordered Moretti's murder after he failed to heed warnings to stay quiet.

Isabella told Villano that Roselli was friendly with New England hoodlums Joseph Lombardi, Phil Buccola, Tony Santaniello and Raymond Patriarca. Roselli's "contact man" in Boston was Rocco Paladino.

Roselli entered Atlanta Prison in 1944.

Siegel

Roselli reportedly had advanced knowledge of Benjamin Siegel's murder in 1947. According to Isabella, Roselli was initially responsible for overseeing Chicago Outfit investments in Las Vegas gambling. Chicago Outfit leader Paul Ricca sent Roselli to Los Angeles to act as a "sottocapo" (underboss) there, and he "extended his influence to Las Vegas." Siegel replaced Roselli when Roselli was arrested in the Hollywood studios extortion case. Roselli claimed he "set up" Siegel when the New York mobster first came to California.

Roselli had been entrusted with $2 million of the Chicago Outfit's money for the development of a Las Vegas casino. Isabella reported that the sum was turned over to Siegel for use in his Flamingo Casino and Hotel project. Siegel managed to lose the sum speculating in the stock market, greatly angering Roselli and his associates.

Roselli and Siegel also had a falling out over a personal matter. Roselli dated an actress named Bernice Ann Frank, who visited him in prison. While Roselli was in Atlanta, Siegel formed a relationship with the actress's sister. According to Roselli, Siegel had been "playing" with the sister and "had almost reduced her to a common prostitute."

Isabella told Special Agent Villano that, two weeks before Siegel was shot to death in Beverly Hills, Roselli predicted the murder. [21]

Ormento

Isabella and Roselli were separated in September 1946. Roselli was transferred to the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, to serve his remaining sentence, while Isabella remained in Atlanta until his November 1950 discharge.

Florio Isabella told Villano he reconnected with Roselli over dinner in a Manhattan restaurant around 1953. Lucchese Crime Family big shot John Ormento joined them, but Isabella indicated that Roselli and Ormento were not close associates. Ormento was a major heroin dealer, more Isabella's racket by then than Roselli's.

Isabella advised that at the end of the dinner meeting, Roselli invited him to move to California and "come in with him." Isabella said Roselli could be reached through the Bella Napoli restaurant in Beverly Hills.

Roselli's girlfriend had visited him at Atlanta Federal Prison. It was a long way to Georgia, but Roselli was wealthy and had no trouble ensuring he had visitors. Isabella wasn't so fortunate.

Isabella grumbled to Roselli that his girlfriend couldn't afford to travel from New York to visit him. Unbeknownst to him, Roselli instructed Peter DiPalermo, a fellow prisoner at Atlanta who was discharged around the same time, to contact Thomas Lucchese when he returned to New York. Roselli got Lucchese to give Margaret Jones $300 so she could visit Isabella. In addition, Roselli ensured that Jones received $50 weekly from Isabella's "friends" until he was released from prison.

Although Roselli initiated the handout and may have provided the money out of friendship, Thomas Lucchese's interest in Isabella's welfare suggests he was a Lucchese Crime Family associate by this time.

Isabella married Margaret Jones in 1950 after his release. [22]

"Conte displayed nice manners and his grammar was superior than mine, but he was a very tough guy. He had led a prison break in New York." [23]

Piscitello

Frank Piscitello was a heroin addict. The thirty-five-year-old native of Queens, New York, fed his addiction by burglarizing homes, sticking up businesses and selling illegal alcohol. [24]

In 1954, Piscitello was sent to detox at a federal prison hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, while serving an eighteen-month sentence for violating his probation by using narcotics. When Piscitello's mother died, authorities permitted him to attend her funeral in New York, where he gave his prison escorts the slip. [25]

Piscitello went on the lam for three months before the FBI recaptured him in a Manhattan apartment on January 18, 1955. He confessed to robbing taverns, restaurants and businesses to feed his massive addiction. Somebody hit Piscitello in the face during one robbery, breaking his jaw. He went to a doctor to get his broken jaw treated. After the doctor patched him up, Piscitello admitted he robbed him of his money and the narcotics kept at the clinic. [26]

Authorities charged Piscitello as a federal escapee and held him at Manhattan's Federal House of Detention at 427 West Street at the intersection with West 11th Street until his trial. (In June 1955, he received an additional three years for his first escape attempt.) While awaiting trial, Piscitello crossed paths with Florio Isabella.

Authorities had just arrested the forty-three-year-old Isabella for heading up a drug distribution ring in Georgia. It was his third heroin charge, and he faced the longest prison sentence of his life if convicted. Isabella was held at the House of Detention between September 21 and September 27 while awaiting bail. During this brief window, Isabella and Piscitello conspired to break out.

New York Times, Dec. 29, 1955.

Somehow, Piscitello obtained diagrams of the building's layout and devised a plan to escape by breaking through the four-foot thick wall of brick and mortar separating the jail from the warehouse next door. He wrote a detailed list of the necessary equipment, including "guns, a portable burning unit, handcuffs, adhesive tape, brace and bit, a ruler and a wristwatch."

Piscitello passed the diagrams and the four pages of instructions to Isabella in an envelope bearing Isabella's Chrystie Street, Manhattan, home address. Isabella, when released in $15,000 bail, then passed the envelope to an unnamed third party, and prison officials intercepted it. Officials said the escape plot had little chance of succeeding because the building's thick walls required the skills of a professional to break through.

On December 28, 1955, Piscitello and Isabella were charged with conspiracy to escape federal custody. Prosecutors called it a "fantastic plot" involving several unidentified individuals. They said Piscitello and Isabella drew up the "perfect" blueprints for the escape. [27] After deliberating for two hours, a jury acquitted them on October 4, 1956. [28]

Atlanta Constitution, Sept. 23, 1955.

Although Isabella was fortunate to avoid a guilty verdict in the prison break, his drug case sunk him. In December 1956, he went on trial, accused of operating a drug ring with a "virtual monopoly" on heroin distribution in the state of Georgia. [29]

According to the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Isabella set up the drug scheme in 1951 when he was released from the Atlanta penitentiary. (It seems more than a coincidence that it was based in Georgia, where he was previously incarcerated.) Isabella transported the heroin to Atlanta by plane once a month, where his Georgia contacts packaged it into smaller amounts and sold it throughout the state. The drug ring profited $100,000 annually during the four years it operated.

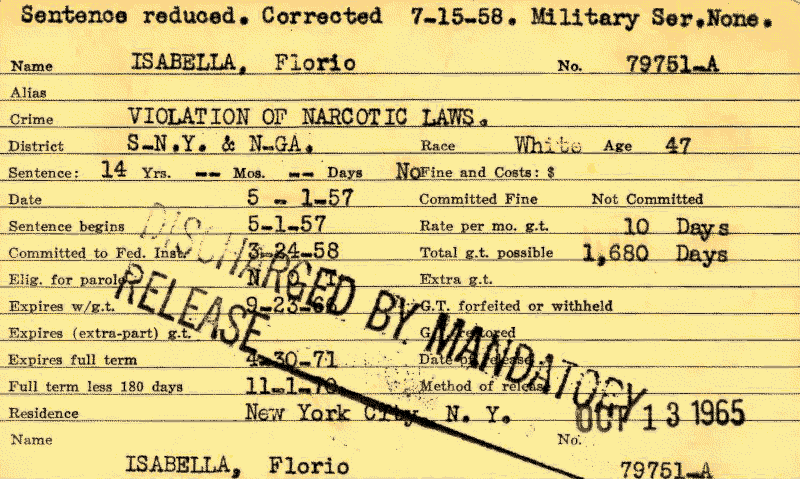

Isabella was convicted and sentenced to fourteen years in federal prison in Atlanta. Four co-defendants, including his nephew, received lesser terms. Isabella remained locked up until October 1965.

Isabella

Special Agent Anthony Villano wrote in his memoir that Isabella informed after federal agents caught him "mid-crime." It was a curious turn of phrase, implying that he didn't quite pull off whatever he was guilty of doing.

Isabella was arrested three times during this period. On February 24, 1955, New York City police arrested Isabella for receiving stolen loot in a $50,000 jewelry heist. He reportedly sold $15,000 worth of rings and watches taken from the heist to a New York jeweler. [30] But the feds were not involved in that investigation.

In September 1955, federal narcotic agents arrested Isabella for heroin trafficking in Georgia. It seems unlikely Villano was talking about this crime, as the trafficking had been achieved before the arrest and agents of the FBI were not involved in the investigation.

That leaves the prison break.

Prison officials never revealed who alerted them to the escape attempt. It's conceivable that the individual Isabella entrusted with the escape documents ratted him out. The FBI participated in the investigation because it occurred inside a federal facility. It's not inaccurate to claim the feds caught him "mid-crime" since the escape attempt never got beyond the planning stage.

Declassified FBI intelligence reports show federal agents identified Isabella as a "PCI" or potential criminal informant by August 12, 1956. The FBI applies the "PCI" designation to an individual at the initial stage of a confidential relationship. The person has shared some information and appears open to sharing more. Such a relationship is not always continued. When it is, the informant is assigned a symbol number. The FBI gave Isabella the symbol number "NY 1839" shortly afterward.

Villano said Isabella partly opened up to agents because they treated him respectfully. What consideration Isabella received from federal agents for his Intel is unknown, but authorities dropped neither the prison break nor narcotics trafficking charges.

During the initial meetings of 1956, the FBI characterized Isabella as "an individual with a criminal record who is in a position to furnish reliable information concerning the lower East side hoodlums." [31] Hoover's Bureau never pursued the relationship, and it went no further until Villano.

Hoover

Several American Mafiosi talked to law enforcement agencies about their secret criminal society before Florio Isabella, but none is known to have worked with the FBI. In the early 20th century, Italian hoodlums arrested for counterfeiting revealed organizational details to the U.S. Secret Service. In the same era, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics developed several confidential informers who described the Mafia-controlled importation and distribution of illegal drugs.

Mobsters like Alphonso Attardi, Dominic Petrelli and Nicola Gentile shared Intel about the organization and criminal activities in the 1940s and 50s. However, the FBN never fleshed out the Mafia's hierarchy, membership and rituals as the FBI would and never developed a "Joseph Valachi-type" individual prepared to publicly expose the organization.

The FBI appears not to have pursued FBN's early leads. Hoover refused to pursue the Mafia. A number of possible motivations for his reluctance have been suggested by various sources: a personal rivalry between himself and former FBN commissioner Harry J. Anslinger; a fear of the corrupting influence organized crime might have on his agents; a belief that local law enforcement was better suited to tackling the criminal organization. It wasn't until the mob meeting in Apalachin that Hoover changed tack.

"One of the revelations was the story of the blinding of newspaper columnist Victor Riesel for his unsolicited interest in the criminal control of some unions." [32]

Victor Riesel

Villano wrote in his memoir that when Florio Isabella talked to FBI agents in the 1950s, he told them "Mafia war stories." One story was the acid attack on muckraking journalist Victor Riesel.

Riesel angered underworld interests by publishing articles critical of the malign influence of organized crime in the labor movement. Mafia labor racketeers tried to intimidate Riesel, but he refused to back down.

Telvi

On April 5, 1956, a Mafia-hired hoodlum named Abraham Telvi surprised Riesel as he left a midtown Manhattan restaurant, throwing sulphuric acid in his face. The attack left Riesel blind and his jaw, cheek and forehead permanently scarred. The incident gripped the city for months.(Despite being permanently blinded, Riesel continued writing his column until he retired in 1990.)

The FBI didn't publicly link the twenty-two-year-old Telvi to the acid attack until August 7, 1956. [33] By then, Telvi was dead. He had taken a bullet to the head at a Mulberry Street corner about ten days earlier. Authorities learned that, following the attack on Riesel, Telvi had demanded more than the agreed upon payment. [34]

Miranti

The FBI arrested two Telvi associates named Gondolfo Miranti and Joseph Carlino. The Bureau said Miranti fingered Riesel for Telvi as he left the restaurant, while Carlino drove Telvi to a hideout in Youngstown, Ohio, until things cooled down after the attack. [35]

Miranti and Carlino both rolled over. Miranti admitted that Lucchese member and labor racketeer "Johnny Dio" Dioguardi masterminded the attack. Miranti was convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice and pleaded guilty to two additional charges of maiming and conspiracy. [36] Authorities charged Dioguardi with conspiracy to obstruct justice but dropped the charges after Miranti recanted his statement and refused to testify.

Although the available FBI intelligence reports and Villano's memoir don't go into what Isabella revealed, his disclosures may have helped break the case open. Isabella was talking to the FBI by at least August 12 (but probably earlier), right in the middle of the FBI's investigation into the attack. Villano used the word "revelation" to describe what Isabella said, which implied he provided significant information the FBI did not previously possess.

Miranti and Carlino were from Isabella's old neighborhood and associated with the same Lucchese element. When Isabella talked in the 1950s, Villano wrote that he furnished incriminating information against "fringe people." At that time, however, he was "always careful not to point a finger at any real wiseguys."

"When [another member source] vouched for Conte, telling me that even Vito Genovese respected him in Atlanta, I became obsessed with the idea of turning him." [37]

Atlanta Federal Prison

Florio Isabella was sentenced to fourteen years in prison on May 1, 1957, after being found guilty of operating the Georgia drug ring. After the courts denied his appeal, he returned to the Atlanta penitentiary on March 24, 1958. It was like a homecoming.

The Atlanta pen was filled with dozens of Mafia traffickers, including Joseph Valachi, Joseph DiPalermo and Vito Genovese. Law enforcement's late 1950s sweep of mobsters was the last time the organization openly backed narcotics trafficking. Afterward, the underworld Commission formally banned narcotics trafficking, and members caught dealing faced severe punishment, including death. Although widely breached, most members exited the business, including Isabella.

Isabella returned to Atlanta Prison in 1958.

An FBI source who did time with Isabella told Villano that Isabella had an excellent prison reputation. In addition, Vito Genovese respected him, and they were reportedly cellmates.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics routinely interviewed prisoners in Atlanta, including Isabella. An FBI listening device in 1963 recorded Buffalo mobsters discussing the meetings between Isabella and drug agent John R. Enright. The unnamed Buffalo mobsters noted that, after meeting with Enright, Isabella reported back to Vito Genovese about their discussion. [38]

Isabella served eight and half years in prison before he was paroled in October 1965. His full term was set to expire on April 30, 1971. If Isabella violated the terms of his parole, he would return to prison to serve the remainder of the sentence.

After transferring to the FBI's New York office in January 1966, Special Agent Villano wrote that he became friendly with an FBN agent, who tipped him off about Isabella. Villano didn't reveal the agent's name. The tip led him to examine Isabella's FBI file and realize that he had divulged confidential information before and was worth recontacting. [39] (It's possible Isabella shared information about his drug network with the FBN.)

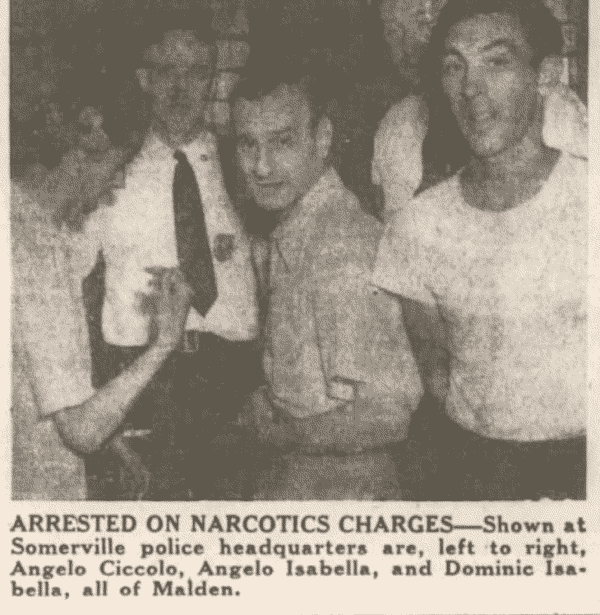

Angelo Isabella and Domenic Isabella arrested

Florio Isabella wasn't the only member of his extended family with ties to organized crime or narcotics trafficking. His cousins, brothers Angelo and Florio Isabella (also named after his grandfather), were active in the Massachusetts underworld. The brothers grew up in the New York area but relocated to the Boston suburb of Malden as adults.

In October 1925, Angelo and Florio Isabella were convicted of dealing heroin in Massachusetts. [59] A judge sentenced the brothers to one year plus a day in Cambridge's House of Corrections.

While cousin Florio was serving his drug sentence, authorities in Newark, New Jersey, charged him with the death of Joseph Rosamilia two years earlier, on April 12, 1923. Rosamilia reportedly tried to kiss Isabella's sixteen-year-old sister against her wishes before the murder. Isabella confronted Rosamilia to protect his family's "honor." A fistfight ensued, and Rosamilia quickly got the upper hand. Isabella pulled out a revolver and shot him in front of multiple witnesses. Isabella entered a plea of "non vult," meaning he was unwilling to admit guilt but was prepared to accept the court's sentence. A judge sentenced him to seventeen to thirty years in New Jersey's state prison. [60]

Angelo Isabella and his imprisoned brother's son Domenic became members of the regional Mafia crime family headed by Raymond Patriarca. Based in the Boston suburb of Malden, they became the state's top heroin traffickers. [61]

In 1949, Angelo and Domenic Isabella were charged with selling heroin to undercover agents. A search of Angelo's residence revealed a quarter kilogram of heroin worth $14,000 hidden in a windowsill. [62] The drugs reportedly came from an unidentified New York source.

Angelo and his nephew pleaded guilty instead of going to trial. A federal judge sentenced Angelo, age fifty, to five years in the penitentiary, while Domenic, age twenty-five, was given three years.

After being released from prison, Domenic Isabella remained active in the drug game, taking over from his uncle as "New England's kingpin narcotics peddler." [63] The twenty-seven-year-old was arrested again in January 1957 after one of his pushers rolled on him and gave up his drug operation. Domenic was sentenced to three to five years in state prison for the illegal sale of heroin. He was also required to serve twenty-one months of his outstanding federal drug sentence for violating his parole. [64]

In September 1962, Domenic was charged again with selling heroin to undercover narcotics agents. He pleaded guilty in January 1963 and was sentenced to ten years in federal prison. [65]

In 1983, law enforcement placed a secret listening device in Domenic Isabella's vehicle. They secured the warrant using Intel furnished by FBI informer James "Whitey" Bulger. The bug produced 1,150 hours of recordings of Isabella and other mobsters discussing murder, extortion, beatings and other criminal activities, leading to numerous arrests. [66] Angelo and Domenic Isabella died in 1988.

"The address was in one of the slummier parts of town, a shabby tenement building. I rang the doorbell; it was answered by a woman I shall call Anne, who Conte lived with and called his wife." [40]

Getting in front of Florio Isabella proved harder than Villano imagined. Isabella lived in New Jersey, and his telephone number was unlisted. [41] Moreover, New York-based Villano wasn't authorized to pursue investigations into the Garden State. Unsure he would get approval from his bosses, Villano went on the sly.

Isabella wasn't home when Villano knocked on his door, but his common-law wife invited him inside. Villano called her "Anne," in his memoir, but evidence suggests her real name was Mary Pantoliano. She and Florio Isabella were distant cousins and formed a romantic relationship when he left prison. Though he lived with Mary Pantoliano until her death, Isabella never divorced Margaret Jones. [42]

Posing as an old prison acquaintance, Villano explained that he wanted to speak with Isabella. "Anne" agreed to pass on a message.

While inside Isabella's home, Villano vainly tried to obtain his telephone number from the home phone, but the number card was missing. Thwarted, Villano mentioned the absence of the number:

"Gee, Anne, what are you, a hooker? You have to keep your telephone number a secret?'

She laughed. 'The [xxx] cops tap the phones all the time, so we try to keep it private." [43]

In the memoir of actor Joseph Pantoliano, Who's Sorry Now: The True Story of a Stand-Up Guy, he recalled living with Isabella, the man he called his stepfather though Isabella never married his mother. Isabella reportedly steered Joseph Pantoliano away from crime and towards acting. However, Pantoliano knew as a youngster that Isabella was on law enforcement's radar. He recalled his mother warning him repeatedly about speaking on the phone because the FBI had supposedly tapped it. [44]

"'The least reward is to be able to say hello to the guy who was the boy friend of ——.' I gave him the name of one of really headliner stars with whom he had shacked up." [45]

Villano eventually met with Isabella in a shopping mall parking lot in June 1966. [46] Isabella was initially uninterested in reestablishing a confidential relationship with the FBI. After years in prison, Isabella told Villano he was done with crime and preferred to be left alone. Villano tried to butter him up by reminding him of his romance with dancer Margaret Jones that made the newspapers in the 1940s.

Villano was a master at finding a subject's sore point and got Isabella to admit he was financially hurting. The only help his underworld associates offered him was to courier drugs which infuriated him since he had the remainder of his sentence hanging over him if he violated his parole.

At their first meeting, Isabella admitted he was a Lucchese Crime Family member and divulged some details about the organization. Isabella took money from Villano and agreed to meet again with the agent. Villano stressed that he only wanted him to furnish "ancient history."

Despite his reservations about talking, Isabella embraced his new role. He had a "gift" for remembering conversations, dates and faces, becoming Villano's most informative CI. [47] Isabella received regular payments from the FBI for his information. Villano stayed in contact with Isabella until retiring from the FBI in 1973. Most of the information furnished by Isabella remains classified by the Bureau.

"Conte was proud of the fact that he was a genuine made guy, even if he felt that the organization had forsaken its virtues and rotted." [48]

Lucchese

Florio Isabella told Special Agent Anthony Villano that the Lucchese Crime Family inducted him in the 1950s. He didn't provide a specific date (in the available FBI intelligence reports), but it must have been in the first half of the decade. Isabella was incarcerated between 1956 and 1965, and crime family memberships reportedly were frozen between 1958 and 1976.

The Lucchese Crime Family was a natural choice for Isabella. The crime family was heavily involved in narcotics trafficking and had a strong presence near his childhood home. While growing up in lower Manhattan, Isabella lived on Mott Street, Mulberry Street, and Chrystie Street. Lucchese Crime Family members, including the Nuccio brothers, the DiPalermo brothers and Joseph Frangipane, resided nearby.

Isabella did prison time with Peter "Petey Beck" DiPalermo, brother of notorious Lucchese heroin trafficker Joseph DiPalermo. When Isabella was locked up in Atlanta during the 1940s, the Lucchese Crime Family supported him financially.

When Villano asked Isabella for details about his induction ceremony, he dismissed it, comparing it to joining the Boy Scouts. Isabella lamented that the organization recently had begun "making people who had never cracked an egg." [49] Isabella explained how he was inducted:

[Isabella] stated that his "caporegima" (sic) then approached [boss Thomas] Lucchese, who together with a number of other bosses asked whether there were any objections to the informant's membership, and when none were voiced, he was "straightened out" (a term used by informant and accepted within New York City LCN "families" signifying being "made.") [50]

In the 1960s New York City underworld, a gang began kidnapping mafiosi off the streets and holding them for ransom. [67] Families quietly paid ransoms and the victims were released unharmed. According to Villano's memoir, the FBI didn't learn of the kidnappings until Isabella informed him.

Using Intel furnished by Isabella, Villano deduced Gambino Crime Family member Joseph Benintende masterminded the kidnappings. Villano interviewed Benintende, but he declined an opportunity to cooperate with the Feds.

Villano shared what he learned with the New York Police Department to help with its investigation. Shortly afterward, Benintende turned up dead. Villano suspected an unscrupulous NYPD detective leaked the information to the Mafia.

He said his initiation contained nothing more than a talk by his "Capo" at which other members of his group were present and during which he was told something to the effect, "You are with us; act like a man, comport yourself as a man and be a man; do nothing before you check with us and be sure to get the ok before you do anything; that if you have a disagreement with another individual who is "made," do not try to settle it yourself, but come to us and we will reach the right settlement; that if you make a good score, tell us, and if it is big enough, share it; that if you leave town or are away, leave a number where you can be reached; and lastly, do whatever we tell you.

[Isabella] stated there was no ritual, such as "burning a holy picture, cutting fingers, or mixing blood" and that this "went out with Balboa." [Isabella] stated on this occasion he was informed that it would be necessary for him to pay dues, but it was expected that in the event there was a marriage, or funeral in connection with a "good fellow" (used by informant to signify a "button man") that he make a contribution of $50.00 or $100.00 if he were doing well.

Isabella's description of a simple ceremony without props or elaborate rituals was similar to the experience of Carmine Taglialatella, another Lucchese Crime Family member source, inducted around the same time. But not all induction ceremonies were performed that way, with rituals differing among crime families, cities and eras. For example, Gambino Crime Family member source Alfredo Santantonio, inducted in 1953, did have his finger pricked and was made to cup a burning holy card in his hands. [51]

"I was smart enough not to profess ignorance about Larry JoJo, although we had not a single reference to him in all our files and this was more than nine years after Apalachin. In fact, it took us a solid year to identify Larry JoJo and his connections. With a little more prodding, Conte gave me the names of the other soldiers in his group. Only a few of them had turned up on our charts." [52]

In his memoir, Villano confessed that when Isabella told him the name of his caporegime - Villano gave him the alias "Larry JoJo" - he and the other Bureau agents had never heard of him.

Available FBI intelligence reports also do not directly answer who Isabella's caporegime was. However, it may be possible to deduce his identity by looking at some of the Lucchese members identified by Isabella.

For example, Isabella identified the following individuals as Mafia members in 1956: Charles Giampaolo, Joseph Frangipani, John Caputo, Samuel Castaldi, the Nuccio brothers - Frank, Salvatore, and Vincent. All these individuals were, at one time or another, part of a Lucchese faction called the Prince Street Crew, headed by Giampaolo. Other members of the crew were Joseph and Charles DiPalermo.

However, the FBI knew very little about Charles Giampaolo in the early 1960s, and he doesn't appear on the membership charts displayed at government hearings in 1963. Villano's observation that "Larry JoJo" was (virtually) unknown to federal agents is consistent with Giampaolo's absence from the Lucchese Crime Family chart.

Santantonio

Former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover prioritized establishing the membership and hierarchy of every crime family. The Bureau used two methods to confirm whether an individual was a Mafia member. It was similar to the Mafia's "friend of mine" and "friend of ours" distinction between associate and inducted member.

The first way was for an existing member source to confirm an individual's membership. For example, when they flipped, Joseph Valachi and Alfredo Santantonio authenticated hundreds of Mafia memberships. Their disclosures were compiled, organized and displayed in the charts and lists at the government hearings into organized crime in October 1963, informally called the Valachi Hearings.

Federal agents also accepted that an individual was a Mafia member if Intel obtained from a listening device confirmed it. For example, if an individual discussed confidential organizational matters in the company of known Mafia members or discussed his induction ceremony, the Bureau took that as a sign that he was a member.

Neither way was foolproof, but individuals were added or dropped over time depending on the latest Intel. Villano described Isabella as "an admitted member," suggesting that he didn't have independent confirmation.

Undermining Isabella's purported membership was the fact that Joseph Valachi, jailed alongside him in Atlanta, never identified him as a member. As a result, Isabella's name was omitted from the membership charts displayed at the government hearings in 1963, compiled mainly using Valachi's information. Member source Alfredo Santantonio also failed to identify him.

When the FBI showed Lucchese Crime Family member-source Carmine Taglialatela a photograph of Isabella in 1969, he grew "visibly agitated with himself over not being able to recognize a photograph of Florinda Isabella (sic), which he said was very familiar. The name Isabella did not prompt his memory, but he said he probably knew him by a nickname." [53]

Isabella possibly was an inducted member, but FBI member sources didn't know him. Or he or Villano misrepresented his status for an unknown reason. [54] Villano noted in his memoir that the Bureau incentivized agents with commendations and financial rewards for developing member sources, leading some agents to exaggerate a mobster's rank for personal gain.

When Isabella talked to federal agents on August 12, 1956, he revealed that Charles Carlino was "a 'button man,' who was 'made,' by the Dioguardi brothers." Johnny and Tommy Dioguardi and their uncle Vincent "Tommy Doyle" Plumeri were prominent Lucchese members. According to Isabella, Carlino gained much underworld stature since he was inducted "6 or 7 years ago." [55]

Isabella may have been the first FBI CI to use the terms "button man," and "made." These terms were generally unknown to the FBI before Joseph Valachi introduced them when he was debriefed in 1962. Isabella referred to the underworld organization as "mob" rather than "Mafia," "Cosa Nostra" or "crime families." The Bureau ignored Isabella's Intel and didn't incorporate it into the 1963 government hearings into organized crime.

According to Villano, Isabella played it straight after parole, working legitimately and declining offers from other mobsters to get back in the game. Instead, he spent the last years working in a restaurant and battling emphysema after decades of smoking. [56]

After cooperating, Isabella's only known legal trouble occurred on March 31, 1970, when police arrested him for violating a New Jersey state law requiring drug offenders to register with the local police chief. [57] Others swept up with him included Vincent Gigante, Benedetto Cinquegrana and Pasquale Genese. The prosecutor called the men "fairly high ranking members of organized crime." Isabella paid a $50 fine.

Florio Isabella died on November 7, 1987, at 76. [58]

Available FBI intelligence reports offer only a glimpse at the information Florio Isabella furnished in 1956. Isabella didn't have Joseph Valachi's deep knowledge of the organization going back to the Castellammarese War. However, based on the assessment of veteran Special Agent Anthony Villano, who saw the files, Isabella's Intel made the existence of the Mafia undeniable.

Former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ignored Isabella's revelations, setting back the Bureau's investigation into the Mafia by several years and significantly impacting the New York underworld.

Had Hoover handled the FBI's first Mafia informant correctly, FBI scrutiny of the organization would have ratcheted up significantly, likely impacting day-to-day operations. As a result, the crucial period immediately after 1956, when Albert Anastasia died, Frank Costello retired and the country's leading Mafiosi met in Apalachin, likely would have unfolded differently.

Thank you to Archivist Nathan G. Jordan of the National Archives at Atlanta for furnishing the Atlanta Federal Prison records of Florio Isabella and Johnny Roselli.

1 Villano, Anthony, with Gerald Astor, Brick Agent: Inside the Mafia for the FBI, New York: Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co., 1977, 40.

2 Brick Agent, 77.

3 Brick Agent, 86.

4 Brick Agent, 77-89; FBI, Johnny Rosselli, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 27, 1966, NARA Record No. 124-10221-10200.

5 Florindo Isabella, New York City Municipal Deaths database, FamilySearch, familysearch.org. His grandfather died in New York City in 1898 at age of 53.

6 Pantoliano, Joseph with David Evanier, Who's Sorry Now: The True Story of a Stand Up Guy, New York: Dutton, 2002, 146-7.

7 Brecher, Edward M., et al., "Consumers Union report on licit and illicit Drugs", Consumer Reports, 1972, chapter 8, available through Schaffer Library of Drug Policy, druglibrary.org/schaffer; Courtwright, David T., "A century of American narcotic policy," Treating Drug Problems Volume 2, available through National Library of Medicine, ncbi.nim.mid.gov, Jan. 14. 2022.

8 "And Some Want Prohibition Back," New York Daily News, March 31, 1943, p. 452.

9 Brick Agent, 78.

10 Who's Sorry Now, 80.

11 "Rum hi-jackers broken up as nine are jailed," New Jersey Courier-News, May 22, 1943, p. 14.

12 Brick Agent, 78.

13 United States Census of 1920, New York State, New York County, Assembly District 5, Enumeration District 411, FamilySearch, familysearch.org; New York City Marriage Licenses Index, 1950-1995, FamilySearch, familysearch.org.

14 United States Census of 1940, New York State, New York County, Assembly District 5, Enumeration District 31-449, FamilySearch, familysearch.org.

15 Radin, Edward, "Cherchez la Femme," Dayton Daily News, July 31, 1949, p. 79.

16 "Hijacker pleads guilty to whiskey load theft," The Buffalo News, Nov. 1944, p. 1; "Inter-state gang of liquor looters said cleaned up," New Jersey Courier News, Sept. 20, 1944, p. 4. Jones was charged with violating the federal harboring statute, but how the charge was adjudicated is unknown.

17 Who's Sorry Now, 80-81.

18 Brick Agent, 86.

19 FBI, Johnny Rosselli, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 27, 1966, NARA Record No. 124-10221-10200.

20 Valin, Edmond, Salvatore Piscopo: The Man Who Betrayed Johnny Roselli," Rat Trap, December 2018.

21 FBI, Johnny Rosselli, Los Angeles Office, Sept. 27, 1966, NARA Record No. 124-10221-10200.

22 United States Census of 1950, New York State, New York County, Enumeration District 31-404, FamilySearch, familysearch.org.

23 Brick Agent, 78.

24 "Big haul," New York Daily News, Dec. 10, 1944.

25 "FBI nabs 5 in New York raid," Poughkeepsie Journal, Jan. 18, 1955, p. 16.

26 "FBI captures a dope with 2 gals," New York Daily News, Jan. 19, 1955, p. 389.

27 "Blueprint of escape drawn by prisoners," Odessa American, Dec. 30, 1955, p. 7.

28 "Jury frees 2 in escape plot," New York Daily News, Oct. 5, 1956, p. 119.

29 "5 indicted in narcotics crackdown," Atlanta Constitution, Sept. 23, 1955, p. 1; "US cracks $20 million dope setup" Miami News, Sept. 4, 1957, p. 3. Isabella was an un-indicted co-conspirator in the 1957 heroin trafficking bust that sent Anthony Mirra, Nicholas Lessa and Martin DeSaverio to prison.

30 "Three New York men held in Boston robbery," Hartford Courant, Feb. 25, 1955, p. 4.

31 "FBI, Charles Salvatore Carlino, New York Office, Nov. 4, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10347-10087.

32 Brick Agent, 77.

33 "Named in blinding of columnist," Moberly Monitor-Index, August 7, 1956, p. 9.

34 "Racketeer, who beat many raps, rubbed out," New York Daily News, July 29, 1956, p. 64.

35 "FBI declares acid throwing case is solved," Redwood City Tribune, Aug. 17, 1956, p. 1.

36 "Riesel case 'finger man' pleads guilty to maiming," Indianapolis Star, Jan. 22, 1957, p. 17.

37 Brick Agent, 78.

38 FBI, La Cause Nostra, Buffalo Office, June 14, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10200-10453.

39 Brick Agent, 78.

40 Brick Agent, 78.

41 Villano's memoir, while mainly accurate, included misinformation to throw the reader off. For example, he described traveling to Connecticut from New York to interview Rico Conte. In reality, Isabella lived in New Jersey. Or Villano described Conte as physically unattractive while Isabella was handsome.

42 Who's Sorry Now, 286-7.

43 Brick Agent, 79.

44 Who's Sorry Now, 145, 177.

45 Brick Agent, 80.

46 Declassified FBI intelligence reports reveal the earliest known date that Villano talked with Isabella was June 9, 1966, although they may have met slightly earlier.

47 Brick Agent, 86.

48 Brick Agent, 81.

49 Brick Agent, 86.

50 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10308.

51 Valin, Edmond, "Gambino mob informants had very different fates," Rat Trap, February 2022.

52 Brick Agent, 82.

53 FBI, SF 3208-C-TE, San Francisco Office, March 17, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10108.

54 Who's Sorry Now, 147. Pantoliano said his stepfather was an associate, claiming Vito Genovese intended to induct Isabella before he died in prison.

55 FBI, Charles Salvatore Carlino, New York Office, Nov. 4, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10347-10087.

56 Who's Sorry Now, 287.

57 "Criscola is fined for failing to register as drug violator," News, June 3, 1970, p. 23.

58 "Obituaries," Hackensack Record, Nov. 9, 1987, p. 3.

59 "Isabella, in jail, accused of murder," Boston Globe, Oct. 30, 1925, p. 2.

60 "17 years for man taken at medford," Boston Globe, May 17, 1927, p. 3.

61 "3 arraigned in Somerville drug seizure," Boston Globe, July 27, 1949, p. 24.

62 "Malden raid nets $15,000 in dope," Evening Express, July 27, 1949, p. 5.

63 "Man called top N.E. peddler of drugs held in $100,000," Boston Globe, Jan. 21, 1953, p. 1.

64 "Malden man gets 5 years on narcotic count," Boston Globe, April 13, 1953, p. 4.

65 "2 get 5-10 years in narcotics case," Boston Globe, Jan. 7, 1963, p. 18.

66 "3 alleged crime bosses plead not guilty, remain in custody," Boston Globe, Dec. 1, 1989, p. 37.

67 Brick Agent, 88.