He was a hoodlum who got crossed up with the Chicago Outfit and turned to the FBI for help. His bombshell testimony put a Mafia boss in prison. Authorities rewarded him with a new identity, but his enemies got the last laugh. Here's the story of the snitch called "John Cerone's Biggest Mistake." [1]

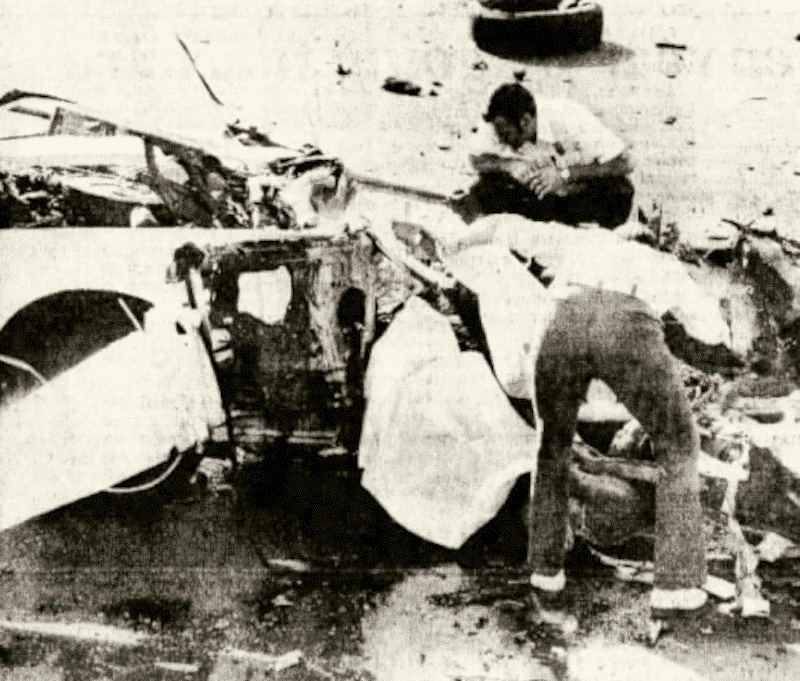

Wreckage of 1975 car-bombing.

Around 8:30 am on October 6, 1975, fifty-two-year-old Joseph Nardi left his apartment building at 201 West Hermosa Drive in Tempe, Arizona. He had lived at the address with his wife and teenage son for the past eight months. Nardi got behind the steering wheel of his leased 1976 Lincoln Continental and started the engine. He backed up only a few feet when a massive explosion ripped through the vehicle.

The blast shattered nearly a hundred windows in the neighborhood, sending metal debris in every direction for a quarter-mile. In addition, the explosion created a crater five inches deep in the pavement beneath the vehicle. [2] When law enforcement arrived, they found Nardi's lifeless body dangling from the open driver's side door, naked except for a shredded t-shirt.

Despite the blast's power, Nardi's body remained intact. An autopsy performed the next day revealed Nardi died of a heart attack. [3]

The car-bombing case took a curious turn when the investigation revealed that the victim's name, Joseph Nardi, was an alias. His real name was Louis Bombacino, and he was a government informer hiding from the Chicago Outfit.

Louis Bombacino

Louis Bombacino, Jr., was born in Chicago, Illinois, on September 8, 1923, to immigrant Italian parents.

His father Louis Bombacino, Sr., - the original spelling of the family surname was "Bambacigno" - was born in Valenzano, in the southeastern Italian province of Bari, in 1893 and came to the United States in 1911. He eventually settled in Flint, Michigan, where he married Carmela Cupolo in 1919. Carmela was born 1897 in Eboli, in the province of Salerno, and emigrated from Italy in 1914. The couple had two sons, Anthony (born in 1920) and Phillip (born in 1922), in Flint before relocating to Chicago. [4]

Louis Jr. grew up in an apartment at 771 West De Koven St., in Chicago's old 20th Ward, near the Outfit stronghold at the intersection of Taylor and Halsted. [5] When he was a teenager, the family moved further south to 1128 South Whipple St. in the 24th Ward.

Federal prosecutor Michael Nash, who got to know Louis Bombacino after he became a government witness, said, "[Bombacino] was in trouble with the law from the time that he had to make a decision between right and wrong and he made the wrong one." [6] Bombacino admitted that he "cheated and lied to make a living when not behind bars." [7]

Bombacino racked up four felony convictions in the 1940s and 50s for crimes like mail theft and forgery and spent a total of ten years in prison. Bombacino had a hard-luck reputation, and when he went to work for the Outfit, they chided him for his inability to stay out of jail.

Bombacino bounced between Illinois and California. In 1959, he lived at 618 South Central Park, Chicago, with his girlfriend, Constance Mistretta. [8] He reportedly married Mistretta, but it was short-lived. He may have married at least three times. One former wife accused him of bigamy.

In June 1961, federal agents arrested Bombacino in Los Angeles and charged him with extorting a married real estate developer. [9] Bombacino threatened to disclose that his own former wife Constance Mistretta was having an affair with the developer unless he paid $2,500. At the time of his arrest, Bombacino described himself as an unemployed baker living in suburban Los Angeles.

In 1964, authorities arrested Bombacino in Chicago on robbery charges. Before he could stand trial, Bombacino fled to Texas, where law enforcement caught up with him. He was transferred back to Chicago on October 27, 1964. [10] While stewing in jail, Bombacino reached out to the FBI to talk.

Bombacino's informant file remains classified, and details behind his recruitment are hard to come by. However, two former FBI agents, William F. Roemer and Vincent L. Inserra, wrote memoirs about their experiences investigating the Outfit and provided inside information about developing Bombacino as a source.

Anthony Bombacino, Louis's older brother, died on April 4, 1965. [44] His death may have contributed to Louis's decision to become a confidential informer three weeks later. Anthony operated a bakery that sold dietetic pastries enjoyed by Outfit leader Paul Ricca. Anthony Bombacino's brother-in-law, Eugene Albano, also a baker, was a Ricca associate. These connections reportedly endeared Ricca to Louis Bombacino.

Inserra stated Bombacino was "previously unknown" to federal agents before cold-calling the office in April 1965. Roemer and Inserra said federal agent Paul Frankfurt took the call and went to see Bombacino in jail. [11] Bombacino agreed to work for federal agents as a paid informant in exchange for probation on the robbery charges. The FBI had little choice but to make deals with hoodlums like Bombacino because they were in the best position to obtain Intel against Outfit members.

Roemer claimed Bombacino flipped because he was "pissed off" that Outfit bosses had ruled against him in "a dispute of his handling of their bookmaking operations." [12] However, Roemer mistakenly referred to the incident in 1967 that caused Bombacino to quit his undercover role and not to his original decision to become a paid informant.

Back on the street, Bombacino hooked up with childhood friend Frank Aureli. Known as "Frank the Knife," Aureli was a forty-six-year-old bookmaker operating in the Chicago suburb of Austin. Aureli reported to Joseph Ferriola, a mob enforcer closely associated with Fiore "Fifi" Buccieri.

The FBI initially carried Louis Bombacino as an inducted Outfit member based on Intel supplied by Louis Fratto. Federal agents William Roemer and Vincent Inserra also referred to Bombacino as "made." However, Fratto lived in Iowa for decades and did not interact with Chicago-based hoodlums regularly. As a result, many of his identifications turned out to be inaccurate. Bombacino did not identify himself as "made," and there is some doubt whether he was. [43]

It's unclear what if any criminal relationship Bombacino had with the Outfit before becoming an FBI informer. Bombacino grew up on the organization's periphery, but the available FBI intelligence reports do not indicate any prior connection. There is reason to believe that the FBI encouraged him to develop a relationship with the organization as part of his deal.

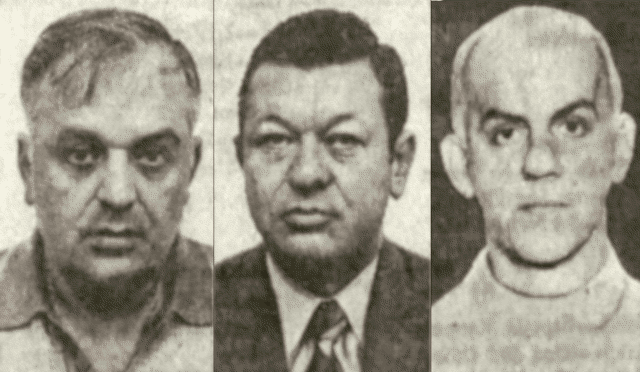

Aureli and Ferriola, along with associates Donald Angelini and Dominic Cortina, operated a multi-million-dollar sportsbook, taking bets across the Midwest. Angelini was the group's handicapper and set the betting line. John Cerone, top lieutenant to Outfit leader Anthony Accardo, oversaw the entire operation. Cerone was a rising star and became the organization's acting boss in 1967.

Bombacino's responsibility was to take bets from customers over the telephone. He initially worked out of Aureli's apartment at 4355 South Sawyer Street in Chicago but changed locations frequently. Eventually, Bombacino had a phone installed and took bets out of his apartment at 2540 North Mannheim Road in Franklin Park, west of Austin. Aureli paid him $200 a week.

Bombacino did not have experience working in a wire room. Aureli showed him how to take bets and write them down in code on special paper that could be dissolved quickly in water if the police raided. Buckets filled with water were kept nearby. [13] Bombacino routinely took bets totaling $15,000 a day, with customers calling from as far away as Cleveland and Detroit. The FBI estimated Cerone's interstate bookmaking operation received $300,000 to $400,000 worth of bets weekly.

The FBI paid Bombacino roughly $3,500 during the approximately two years he worked undercover supplying information.

Joseph Ferriola, Dominic Cortina and James Cerone (left to right).

The FBI assigns a symbol code to every confidential informer. The symbol code is a unique identifier that allows federal agents to record an informer's disclosures without revealing his true identity. A typical FBI intelligence report will only give the source's symbol code, not his name. (In fact, government censors usually redact even the symbol codes before declassifying an intelligence report.) Furthermore, the FBI will keep the informer's symbol code secret even after he dies.

However, by studying FBI intelligence reports for clues, it's sometimes possible to pinpoint a likely informant suspect. Trying to determine Bombacino's symbol code is made easier because he was a known informer who testified in court about specific information.

In Bombacino's case, the evidence strongly suggests his symbol code, disclosed here for the first time, was "CG 6884." Numerous clues point to Bombacino and "CG 6884" being the same, but here are three of the most compelling:

Inserra

1. Meeting - At John Cerone's trial in 1970, Louis Bombacino testified that Cerone introduced him to a "man named Al" at Armand's Pizzeria in January 1967. Cerone advised him not to worry about police interference "because Cerone knew a judge who would take care of things if Bombacino were arrested" (United States vs. Cerone, 452 F.2d 281). Bombacino's testimony corresponded to Intel supplied by "CG 6884" three years earlier. In an FBI intelligence report dated January 1967, "CG 6884" spoke of attending a meeting at Armand's with Cerone and an individual named "Al." At that meeting, Cerone stated "Al" was his connection to a corrupt judge who would help if "CG 6884" got arrested. [14]

2. Handler - Former FBI agents William Roemer and Vincent Inserra indicated that Louis Bombacino's FBI handler was Paul Frankfurt. [15] Declassified intelligence reports show the bulk of contacts between the FBI and "CG 6884" were with Paul Frankfurt. [16]

3. Active dates - In an intelligence report dated September 1967, the FBI described "CG 6884" as formerly active in the Chicago underworld. [17] However, a different intelligence report shows "CG 6884" was active as late as May 17, 1967. [18] The two reports together indicate that "CG 6884" stopped informing sometime in the summer of 1967. Louis Bombacino testified his undercover role ended in August 1967.

Bombacino's informant file remains classified. However, some never-before-seen Intel secretly furnished between 1965 and 1967 is revealed here for the first time.

Collecting gambling debts could be aggravating, especially when other mobsters got involved. For example, Bombacino told federal agents about a bettor that owed Frank Aureli $1,500. [45] The bettor reached out to Joseph Ferriola, who instructed Aureli to forget about the debt. Not satisfied, Aureli contacted a high-ranking mobster named Gus Alex to intercede for him. Alex reached out to hoodlums Leonard Patrick and Joseph Bulger for assistance and was able to get Aureli his money.

Yaras

Another time, Bombacino told federal agents that his associates Frank Aureli and Dominic Cortina pressed two Jewish bettors to repay their gambling debts. The bettors reached out to Jewish mobster Dave Yaras to intercede for them, and he got Cortina to back off. [46]

Louis Bombacino spent many years incarcerated or living outside of Chicago, so his understanding of the Outfit was limited. As a result, the Intel, collected from various intelligence reports, does not follow a narrative and skips between different hoodlums. The FBI knew much of it from other sources, but Bombacino gave an inside perspective that law enforcement used to make criminal cases against prominent Outfit members.

Aureli

As a member of Frank Aureli's bookmaking crew, Bombacino was well-informed about the Outfit's moneylending operations. Called "juice loans," these high-interest-rate loans were the organization's bread and butter. Bombacino said every prominent Outfit member had a juice racket with a specific territory and lender network.

Outfit loansharks served borrowers, like gamblers, criminals or business owners who couldn't get loans from mainstream lending institutions. Outfit loans were convenient but came with significant risk. The interest rate could be as high as twenty percent a week, and if a borrower missed an interest payment, a goon might break his arm.

Bombacino said the organization had so many customers that it had a "clearinghouse" to handle the volume of loans. [19] If a mobster wanted to lend money out, he would first telephone the clearinghouse to ensure the potential customer did not have any outstanding loans from other Outfit members.

Bombacino advised that Fifi Buccieri, John Cerone and Sam DeStefano were the biggest juice operators. He called DeStefano "the king of the juice rackets."

William Daddano, a close associate of former Outfit boss Sam Giancana, was DeStefano's sponsor in the Outfit. According to Bombacino, Daddano and Giancana were "pals as boys and burglarized drug stores together." He said they "grew in power together."

Bombacino stated Daddano controlled Outfit activities in McHenry, DuPage and Kane counties. He owned coin-operated machine (jukebox and pinball) companies and liquor stores and operated extensive bookmaking and gambling rackets. Joseph Amato and Buck Clementi were Daddano's "primary lieutenants in the overall operation of these counties." [20]

Charles Nicoletti was another large operator. His two lieutenants George Dicks and Sam Cesario, worked out of a gas station on the city's West Side. Buccieri's top two lieutenants were Joseph Ferriola and Turk Torello.

Ricca

According to Louis Bombacino, Outfit leaders met every Sunday afternoon at Paul Ricca's home in River Forest, Illinois. [21] The leadership group included Sam Giancana, Anthony Accardo, Sam Battaglia and Sam Lewis. [22] Bombacino called them the five fingers of the "Black Hand." Sam Lewis, a relatively unknown Outfit member, was among Ricca's best friends.

Bombacino advised federal agents that the Italian criminal organization in Chicago was known as the Syndicate, the Black Hand or the Mafia. He indicated that Chicago hoodlums do not refer to "Cosa Nostra," the term popularized by Joseph Valachi, as the organization's actual name.

Bombacino stated that Ricca was the top boss, despite all the attention Accardo and Giancana received from law enforcement and the press. Bombacino stated most hoodlums would agree with him on this detail.

Bombacino said Joseph Esposito, a city employee, was a good friend of Ricca and was known as his "right arm." Esposito knew Ricca back in Italy. Another close Ricca associate was mob lawyer Joseph Bulger.

Joseph Giancana told Bombacino in 1967 that he didn't expect his brother Sam would ever return to the United States. [23]

In the early 1960s, Bombacino, a heavy gambler, spent time in Las Vegas and learned about the Outfit's casino operations. He told federal agents the Outfit controlled the Stardust Hotel and Casino. He said casino operators John Drew and Tommy McDonald "fronted" at the Stardust Hotel on behalf of the racketeers. Bombacino stated the Outfit had an interest in the Fremont Hotel and Casino but the Genovese Crime Family controlled it.

William Daddano and Mike Patrick, brother of Jewish hoodlum Lenny Patrick, traveled every month to La Vegas to collect Chicago's "skim money" from the casino operations. Bombacino called Daddano and Patrick the Outfit's "bagmen." [24]

After federal law enforcement began to investigate Italian organized crime, former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover emphasized the need to identify every Mafia member. By the time Bombacino talked, the FBI's Chicago office had pinpointed most of the Outfit's existing membership, but gaps remained. Through Bombacino's efforts, the FBI added more mobsters to the verified membership list, including Donald Angelini, Dominic Cortina and Sam Ariola. [25]

John Cerone's bookmaking operation made $4,500, taking bets on the National Football League's first Super Bowl game between the Green Bay Packers and Kansas City Chiefs. The Packers, thirteen-point favorites, won 35-10. [47] According to Bombacino, all of Cerone's customers lost after taking the Chiefs to beat the spread.

Bombacino's undercover role ended abruptly on August 12, 1967, when James Cerone, a member of the gambling crew and John Cerone's cousin, telephoned him at home and advised Bombacino that he was no longer taking bets for the group. [26] According to Bombacino, Cerone did not explain himself, but Bombacino interpreted the call as a threat and went into hiding. It was later reported that the organization had discovered that Bombacino was an informer.

However, former FBI agent Vincent Inserra recalled the matter differently. According to Inserra, Bombacino quit his undercover role and ran to the FBI because he got caught pocketing Outfit gambling funds. [27] Cerone had ordered him to repay the stolen money or else. The criminal organization only discovered Bombacino was an informer after he went into hiding.

Bombacino's debriefing occurred at a farm thirty-five miles west of Chicago, owned by the local district attorney. Over many weeks, Bombacino divulged everything he knew about the Outfit and John Cerone's gambling operation. [28] Federal agents guarded him around the clock, working shifts of twenty-four hours on and twenty-four hours off. Bombacino was good company, and Roemer and his colleagues grew to like him. He prepared Italian meals for them and would send agents into town to purchase the necessary ingredients. Roemer described it as a "fine time."

Bombacino initially hesitated to testify in court against his former associates. However, authorities ultimately persuaded him to take the stand when it became clear that the Outfit already was gunning for him, and he had nothing to lose.

Ricca, 72, brought into federal court on a stretcher. (Chicago Tribune)

In February 1969, U.S. Attorney Michael Nash charged John Cerone, James Cerone, Donald Angelini, Joseph Ferriola, and Frank Aureli with operating a multi-million interstate gambling enterprise. [29] Bombacino, who had been living in Arizona for the last two years under the alias "Joseph Nardi," was brought back to Chicago to testify.

According to Nash, Bombacino was the "key witness." [30] He became the first inducted Outfit member to testify willingly in court against his former associates. (His membership status is not certain.)

Nash conceded that Bombacino was not the best witness. He appeared "visibly shaken" on the stand and coughed up blood. [31] Bombacino had a hard time recalling dates and events, and defense attorneys crossed him up repeatedly. However, the jury found Bombacino's testimony persuasive when he furnished copies of gambling records and betting receipts that laid out the entire betting operation. [32] It's clear from the testimony that the coaching Bombacino received from the FBI before working undercover laid out precisely what law enforcement would need from him to make a successful criminal case.

In May 1970, the defendants were found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison and fines of $10,000. (Aureli suffered an appendicitis attack during the trial and was severed from the case. He was convicted separately and sentenced to eighteen months.) Cerone became the third consecutive Outfit boss, after Sam Giancana and Sam Battaglia, taken down by the FBI since 1965.

The trial was noteworthy for the embarrassment it caused Paul Ricca, whom Bombacino called Chicago's most influential mobster. Bombacino testified Cerone and Ricca discussed the gambling operation in his presence at a meeting on December 28, 1966. Bombacino claimed Cerone "praised" him and told him that "I've heard nothing but glorious reports about you." Ricca agreed, saying, "He's okay." [33] Ricca's endorsement led to a promotion and raise in pay.

Prosecutors called Ricca to corroborate Bombacino's testimony. The ailing seventy-two-year-old crime boss was brought into the courtroom on a stretcher and testified from a wheelchair.

Ordinarily, Ricca would have declined to answer questions because of his right not to incriminate himself. However, the prosecution outwitted Ricca by granting him immunity, compelling him to testify. It left Ricca with a conundrum - keep his mouth shut and go to jail for contempt, or answer questions and break his oath of silence. It was the same legal maneuver that authorities used to imprison former Outfit boss Sam Giancana for a year.

However, Ricca surprised the court by agreeing to act as a government witness to save his skin. He corroborated parts of Bombacino's testimony, sealing Cerone's fate and sending him to prison.

According to a strict interpretation of Mafia rules, Ricca's testimony violated the underworld code of omertà and should have had severe consequences. However, Ricca's age and prestige saved him from repercussions.

The FBI wrestled over what to do with Bombacino after he quit the Outfit. Living in Chicago under his real name was impossible since the Outfit had reportedly issued a murder contract on him. A witness protection program, a federal mechanism designed to relocate and protect government witnesses, did not exist in 1967. (The Witness Security or WITSEC program was established in 1970.) The FBI could not automatically shuffle Bombacino off somewhere safe as they did with later high-profile informants. However, federal agents felt obligated to put their heads together and develop a solution.

Peters

Walter Peters, a former agent in the FBI's Chicago office, had transferred to Phoenix ten years earlier. His former colleagues asked Peters to help them out. So Peters traveled to Chicago to meet with Bombacino on August 23, 1967. [34] Peters spent a week getting to know Bombacino. Finally, Peters and the Chicago office agreed to relocate Bombacino and his family down to Arizona.

The FBI provided Bombacino with a new identity, Joseph Nardi, and a new Social Security number. [35] By September 25, Bombacino was living in the small town of Buckeye, thirty-five miles west of Phoenix. [36] Peters got him a job at the Arizona Public Service, a giant utility company, sweeping floors for $400 a month. Bombacino agreed to return to Chicago in the future when prosecutors needed him to testify.

The FBI informally kept on an eye on Bombacino, and he adjusted well at first. His co-workers at APS called him "friendly" and said he had a "good sense of humor." Company officials promoted him twice, and he was soon earning $880 a month.

However, Bombacino could not leave behind his old ways. He began acting belligerently at work and in public. [37] He threatened a stranger with a .357 Magnum revolver, and he beat an acquaintance to a "pulp" after he damaged Bombacino's car. An inveterate gambler, Bombacino played high-stakes poker seven nights a week, making bets well beyond what he could afford on his salary. In addition, he had a side hustle selling discounted television sets, refrigerators and freezers. His teenage son's bank account inexplicably held $38,000.

In 1974, the Maricopa Sheriff's department arrested Bombacino for stealing expensive company farm equipment. They also tied Bombacino to a gambling and prostitution ring.

The charges were dismissed at a preliminary hearing by the judge after determining the state failed to prove probable cause for their arrest. The law enforcement action infuriated Bombacino, and he sued the sheriff's department for $4 million for wrongful prosecution. He also sued APS to be reinstated to his old job.

Bombacino's decision to sue likely led to his murder. Arizona authorities, unaware of his true identity, began to dig into Nardi's background. They forwarded his fingerprints to law enforcement in his supposed hometown of Chicago. [38] The inquiry revealed Nardi's real name. The FBI speculated that someone in Arizona law enforcement subsequently leaked Bombacino's identity and location. Bombacino also exposed himself by using his real name in his lawsuits.

The FBI warned Bombacino to leave Arizona for his safety. He ignored them and instead relocated forty miles east to Tempe. "Lou had a hard time taking advice," former federal prosecutor Michael Nash said. [39] The decision to remain in Arizona cost him his life.

John Cerone

Bombacino's death upset former FBI agent William Roemer. "It was a very sad day for all of us - not only because Lou Bombacino was a really nice guy and our pal but also because of the deterrent factor. Obviously, it is very tough to develop sources and witnesses when they find out what happened to guys like Lou Bombacino." [40]

Bombacino's murder remains officially unsolved. Federal law enforcement determined the bomber wired the explosive device to the car's accelerator or its steering wheel. That was unusual, since car bombs generally trigger by turning on the ignition. Investigators could not trace the origins of the explosive nor locate witnesses who saw it planted. The FBI called it a "professional job," and figured the Outfit was behind it but could not prove it. The Outfit killed another informant similarly twenty years earlier. [41]

A snitch told federal agents that Anthony Amadio, former henchman of deceased Outfit leader Frank Laporte, tracked Bombacino to Tempe and tipped off the bosses. [42] John Cerone, who was released from the Leavenworth, Kansas, federal penitentiary in 1973, allegedly dispatched a hitman to eliminate Bombacino.

1 "Hoodlum reluctant at Cerone trial," Chicago Daily News, April 28, 1970.

2 "Informer Lou Bombacino lived well with new identity until the day of the explosion," St. Petersburg Times, Oct. 10, 1975.

3 Vincent L. Inserra, C-1 and the Chicago Mob, Xlibris LLC, 2014, 179.

4 Illinois, Cook County, Birth Certificates, 1871-1949; Luigi Bombacigno Naturalization Petition, No. 335372. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, July 1950, certificate no. 6624890 issued; Luigi Bombacigna Certificate of Arrival, No. 11-309115, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, issued April 23, 1941; Carmela Bambacigno Declaration of Intention, Cook County IL Superior Court, Aug. 8, 1927; Carmela Bambacigno Naturalization Petition, No. 83424, United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Nov. 6, 1929.

5 United States Census of 1930, Illinois, Cook County, Chicago, Ward 20, Enumeration District 16-2588; United States Census of 1940, Illinois, Cook County, Chicago, Ward 24, Enumeration District 103-1521.

6 "Informer Lou Bombacino lived well with new identity until the day of the explosion," St. Petersburg Times, Oct. 10, 1975.

7 "Ricca sought as gambling witness," Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1970.

8 "Marriage Licences," Suburbanite Economist, Feb. 18, 1959.

9 "Montrose Man charged with extortion," Pasadena Independent, June 1, 1961.

10 "Suspect transferred," The Odessa American, Oct. 28, 1964.

11 However, the available intelligence reports indicate federal agent John Bassett conducted the earliest debriefings.

12 William F. Roemer, Jr., Accardo: The Genuine Godfather, New York, Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1995, 296.

13 "Witness tells of aiding on Cerone job," Chicago Tribune, April 22, 1970; United States v. John Philip Cerone, Sr., et al., United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, Feb. 28, 1972 (452 F.2d 274), Justia: U.S. Law, justia.com.

14 United States v. John Philip Cerone, Sr., et al., United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, Feb. 28, 1972 (452 F.2d 274), Justia: U.S. Law, justia.com; FBI, Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program, Chicago Office, Jan. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-90059-10073.

15 Special Agent Paul Frankfurt retired in 1970, after twenty-seven years of service.

16 FBI, Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program, Chicago Office, Jan. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-90059-10073.

17 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Chicago Office, Sept. 25, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10279. "CG T-9 [CG 6884] is an individual who was active in the organized criminal element in Chicago."

18 FBI, Samuel Giancana, Chicago Office, July 18, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10116.

19 FBI, CG 6884, Chicago Office, June 4, 1965. 92-689-162. (Sam Battaglia File #3, 179.); FBI, CG 6884, Chicago Office, May 7, 1965. 92-914-247. (Sam Battaglia File #3, 143); FBI, Samuel Giancana, Chicago Office, Aug. 16, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10199-10048.; FBI, Samuel Giancana, Chicago Office, Sept. 6, 1966, NARA Record No. 124-10198-10112. Louis Bombacino can be linked to additional FBI intelligence reports (with redacted informant symbols codes) through similar interview dates and content. For example, in the intelligence report dated May 7, 1965, the FBI interviewed the informer on April 26 and April 29, 1965. These dates corresponded to dates "CG 6884" was known to be interviewed. And again, the intelligence report dated June 4, 1965, and the intelligence report dated August 16, 1965, show similar links.

20 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Chicago Office, Sept. 25, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10279.

21 FBI, CG 6884, Chicago Office, June 4, 1965. 92-914-259. (Sam Battaglia File #3, 175.)

22 FBI, Samuel Giancana, Chicago Office, Sept. 6, 1966, NARA Record No. 124-10198-10112.

23 FBI, Samuel Giancana, Chicago Office, July 18, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10208-10116.

24 FBI, Leonard Patrick, Chicago Office, June 7, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-90075-10019.

25 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Sept. 26, 1968, NARA Record No., 150-159. In this report, Bombacino's informant symbol code "CG 6884" is identified as source "T-200."

26 "U.S. Witness against Chicago Mobsters is murdered as car explodes in Tempe," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975; "Blast cuts short life of mob informer," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975; "Witness tells of aiding on Cerone job," Chicago Tribune, April 22, 1970.

27 C-1 and the Chicago Mob, 179.

28 William F. Roemer., The Enforcer: Spilotro The Chicago Mob's Man Over Las Vegas, Toronto, Ivy Books, 1995, 76-77.

29 "U.S. Witness against Chicago Mobsters is murdered as car explodes in Tempe," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975. "Blast cuts short life of mob informer," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975.

30 "Informer Lou Bombacino lived well with new identity until the day of the explosion," St. Petersburg Times, Oct. 10, 1975.

31 C-1 and the Chicago Mob, 182.

32 "U.S. Witness against Chicago Mobsters is murdered as car explodes in Tempe," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975. "Blast cuts short life of mob informer," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975.

33 "Ricca sought as gambling witness," Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1970; "Cerone, boss of mob here, found guilty," Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1970.

34 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Chicago Office, Sept. 25, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10279.

35 While the surname's origins are unknown, it was similar to the maiden name of his former wife, Yolanda Nardella.

36 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Chicago Office, Aug. 26, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10288-10421.

37 "U.S. Witness against Chicago Mobsters is murdered as car explodes in Tempe," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975. "Blast cuts short life of mob informer," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975.

38 C-1 and the Chicago Mob, 179.

39 "Informer Lou Bombacino lived well with new identity until the day of the explosion," St. Petersburg Times, Oct. 10, 1975.

40 William F. Roemer, Jr., Roemer: Man Against The Mob, New York Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1989, 334.

41 "U.S. witness against Chicago mobsters is murdered as car explodes in Tempe," Arizona Republic, Oct. 7, 1975. The Outfit apparently tracked down informer William Bioff to Arizona in 1955 and killed him in a car bombing.

42 "Tocco, aide to pay the price for 'frivolity'," Arizona Republic, June 30, 1984; "I'm no snitch," Arizona Republic, April 7, 1984.

43 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Chicago Office, Aug. 26, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10288-10421. Louis Bombacino (T-10 in this report) identified other Outfit members but not himself. However, Louis Fratto (T-1 in this report) identified himself plus other Outfit members. Bombacino's lack of self-identification suggests he was not an inducted Mafia member.

44 "Death Notices," Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1965.

45 FBI, Gus Alex, Chicago Office, Oct. 6, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10084.

46 FBI, Dave Yaras, Chicago Office, Feb. 12, 1973, NARA Record No. 124-90073-10053.

47 FBI, Top Echelon Criminal Informant Program, Chicago Office, Jan. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-90059-10073.