John Battaglia in 1958

A distressed woman walked into the Hollywood Station of the Los Angeles Police Department on August 14, 1961. [1] The thirty-year-old mother of two young boys told officers her husband "slapped her around during a quarrel," and threw her out of their home at 2912 Nichols Canyon Road. The husband, who followed his wife into the police station, was arrested. He was charged with battery and disturbing the peace, and spent the night in jail.

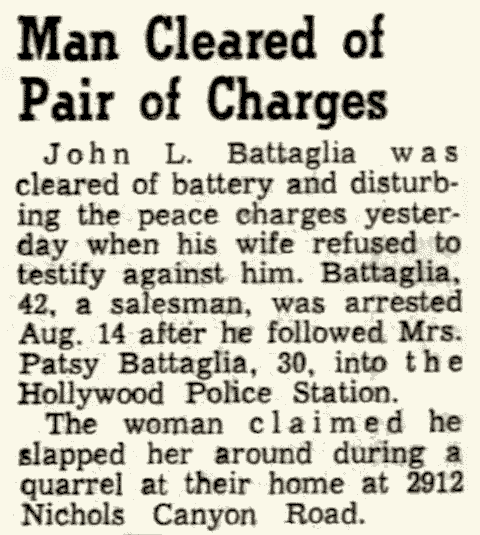

Hollywood Citizen-News, Sept. 12, 1961.

The unfortunate incident had unforeseen consequences for the people involved and for the underworld organizations of Los Angeles, New York and Tucson, Arizona. Authorities dropped the charges a month later when the woman refused to testify against her husband. By then, the Federal Bureau of Investigation had gotten its hooks into one of California's most notorious crime figures.

Investigating Mafia groups became an FBI priority in 1957 after law enforcement stumbled upon a board meeting of underworld leaders at Apalachin, New York. The conclave, bringing together as many as one hundred Mafiosi from around the country, brought to light the organization's power and influence. Its discovery demonstrated a need to change the FBI's policy of generally leaving investigations to local law enforcement.

The Bureau employed two primary methods to broaden its understanding of the organization's membership, structure, and rituals.

First, federal agents installed listening devices in Mafia hangouts to record unsuspecting mobsters discussing criminal activities. The FBI's Chicago office was credited with the first successful electronic surveillance device installation in 1959. It was placed in the unofficial headquarters of the local organized crime family.

Second, the FBI implemented a covert program to develop confidential informers inside the Mafia who could furnish firsthand information about the organization. The inside sources could cooperate secretly, never testify in court and remain anonymous even after they died.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover on June 21, 1961, issued a top-secret memorandum with guidelines on how federal agents should develop confidential informers or CIs. [2]

Hoover

Hoover ordered each FBI field office to select a group of agents to work exclusively on developing CIs. The agents had to be "mature," "aggressive," and "resourceful," with proven track records. In addition, they needed to be "enthusiastic" and have the "will and desire to employ new approaches and means to secure the Bureau's goals." He emphasized that a "prime objective of the Bureau" was developing "quality" informers.

Hoover gave federal agents wide latitude to convince individuals to cooperate. For example, they could offer financial incentives to mobsters or their family members to persuade individuals to talk. Or if offers of financial incentives were ineffective, agents could use coercive measures like blackmail or threats of deportation for unresponsive mobsters.

John Battaglia

The FBI director identified twenty-one hoodlums nationwide that federal agents should consider targeting. He implied the hoodlums exhibited a "vulnerability to development" based on information obtained from previous investigations. Individuals on the list included Jimmy Fratianno in California, Louis Lederer in Las Vegas and Pasquale Massi in Philadelphia.

Hoover's hunches paid dividends for the Bureau down the road. Fratianno and Lederer became informers in the 1970s. Although there is no evidence Massi was persuaded to inform, he was arrested on a charge of sodomy in a public park that federal agents tried to exploit for that purpose. [3]

In Los Angeles, Hoover highlighted forty-two-year-old John "Bat" Battaglia. A former associate of racketeer Mickey Cohen, law enforcement described Battaglia as a "bookmaker, muscle man [and] gunman." [4] He was the brother of Mafia member Charles Battaglia.

Just two months after Hoover's recommendation, Battaglia allegedly assaulted his wife. The FBI leveraged Battaglia's legal troubles to compel him to become a CI against the Mafia. [5] He was assigned informant symbol code "LA 4335."

John Battaglia's cooperation, while never officially confirmed, can be deduced from comparing facts about him with details of a documented FBI informer referred to by the symbol code "LA 4335." Battaglia and "LA 4335" match in five ways:

John Louis Battaglia was born on June 24, 1919, in Farnham, New York, a village twenty-six miles south of Buffalo on the shores of Lake Erie. Battaglia was the youngest of seven children born to Sicilian immigrants Charles Battaglia and Gaetana (Ida) Randazzo. He was related to the Pieri brothers in the Buffalo Crime Family through his maternal grandmother Cecilia Pieri.

Battaglia moved to California in the 1940s. His older brother Charles Battaglia had established himself in Los Angeles as an associate of mobsters Jimmy Fratianno and Johnny Roselli in gambling and bookmaking operations. Charles reportedly participated in the gangland slayings of hoodlums Anthony Trombino and Anthony Brancato in 1951. As a reward, southern California boss Jack Dragna inducted Charles into the regional crime family in 1952.

John Battaglia was arrested multiple times during the 1940s and 1950s for bookmaking but was never convicted. However, he served six months in federal prison in 1946 for "black market operations" during the Second World War. [6] [7] He frequently used the alias "John Bennett."

In November 1958, California's State Assembly rackets committee summoned John Battaglia and other leading mobsters, including Mickey Cohen, Louis Dragna, and Nick Licata, to answer questions about the Mafia's infiltration into gambling and bookmaking.

Battaglia was described as an "underworld character of major importance." [8] The committee quizzed Battaglia about his alleged Mafia affiliation, but he declined to answer questions. [9] As a result, he was charged with contempt, but the charges were later dropped "in the interest of justice." [10]

Despite Battaglia's important connections in the Los Angeles underworld, he was never more than a Mafia associate. Los Angeles Crime family member Salvatore Piscopo advised federal agents that Battaglia was "anxious" to join the Mafia and was "popularly thought" by law enforcement to be a member but "had never been accepted by it." [11] Piscopo stated that the Mafia was a "tight, well disposed, hard-core organization," but he implied Battaglia did not possess the right qualities.

Reporters described John Battaglia as suave and handsome. His dapper appearance and easy charm served him equally well in dealings with businessmen and with hoodlums. Unlike his brother Charles, who had a violent reputation, John preferred making a score using a good word instead of a gun.

On January 27, 1958, John Battaglia was arrested in Dallas, Texas, for swindling $10,000 from a Wichita Falls oilman. [13] Battaglia convinced Clint Broday, a man he barely knew, to give him money to buy a racehorse in California. He claimed the horse was a "sure winner." Authorities said Battaglia misrepresented material facts in the sale and charged him with obtaining money by fraud. Battaglia countered that it was a "legit deal." However, he reportedly committed three similar scams. Broday called Battaglia a master salesman: "I wish I had him selling tires and batteries for me; I'd be a rich man."

Battaglia spent several nights in jail until he signed a waiver returning Broday's money, minus $200 Battaglia spent. When Battaglia was discharged, he handed his last two dollars to a prison guard with instructions to give it to a prisoner facing a murder charge.

When officers arrested Battaglia, they found two small bottles containing codeine and barbiturate pills in his pocket. [14] He was charged with possession of narcotics. It's unclear how this charge was adjudicated.

John Battaglia's underworld notoriety led authorities to include him in the Nevada Gaming Control Board's first Excluded Person List. [15] Sometimes known as the "Black Book," the Excluded Person List was established in 1960 by state regulators to keep organized crime figures with convictions for gambling-related crimes from entering casinos. It was intended to maintain the integrity of the gambling industry.

Individuals on the list could be charged if they entered a gambling establishment in Nevada. Authorities could also punish casino owners with fines and penalties if they did not report the incident. That first "Black Book" contained the names of just eleven people, including well known crime figures Sam Giancana, Murray Humphreys and Marshall Caifano of Chicago; Nicholas and Carl Civella of Kansas City; and Louis Tom Dragna of Los Angeles. Jimmy Fratianno wrote in his memoir that Battaglia skipped out on a $4,500 casino debt.

John Battaglia married twenty-three-year-old Patsy Gene Mink in a Catholic ceremony in Los Angeles on January 6, 1955. [16] Patsy was born in Idaho and grew up in Oregon. The couple had two sons.

Patsy Battaglia

Battaglia's frequent brushes with the law and the publicity surrounding his organized crime ties strained their relationship. After six years of marriage, the couple separated in April 1961, and Battaglia moved out of their Hollywood Hills home. Battaglia reportedly agreed to pay his wife $200 monthly in alimony and child support as part of their separation agreement. He also paid her $500 monthly toward the mortgage. [17]

Authorities charged Battaglia on August 14, 1961, with attacking his wife at the home they once shared. The district attorney later dismissed the charges, when Patsy refused to testify against him. The incident led to Battaglia cooperating with the FBI.

Battaglia and his wife reunited briefly, but the marital discord escalated. In the early evening of October 28, 1961, police were called to the Battaglia residence. [18] They found Battaglia lying face down on the kitchen floor, bleeding from a gunshot wound. An ambulance rushed him to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, where surgeons removed a bullet from just below his heart. The doctors told Battaglia he was lucky to be alive.

John Battaglia furnished conflicting information about the incident. He told the responding officer, who found him lying on the kitchen floor bleeding, that the shooting was an accident. But as the officer questioned him about the incident, Battaglia blurted out that he had tried to commit suicide. [19]

Wounded John Battaglia

While Battaglia was undergoing surgery at the hospital, investigators searched the house and found a .38 caliber revolver tucked away in a bedroom drawer, far from where Battaglia lay bleeding. Two cartridges were missing from it. In addition, they noticed someone had tried to clean up the crime scene before emergency services arrived by wiping up blood off the kitchen floor with a towel.

Investigators found a note allegedly written by him indicating he had shot himself. "I shot myself. I don't know what came over me." [20] However, the bullet's entry point made investigators skeptical that Battaglia did it. Instead, they suspected Battaglia's wife Patsy wrote the suicide note afterward.

Authorities charged Patsy Battaglia with suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon. They did not believe her husband's version of what happened, and she was the only other person in the house at the time of the shooting. They reckoned Patsy attempted to shoot at him in the bedroom and missed before hitting him in the kitchen. [21] The couple's two children were outside playing. Patsy said she was watching television when she heard the shot.

Patsy spent the night in jail. She was released the next day after posting $525 bail. The district attorney dropped the charges because of her husband's conflicting statements to the police. [22]

John and Patsy Battaglia divorced in March 1962. A judge initially awarded John custody of the children based mainly on the allegation that his former wife shot him. However, Patsy regained custody in October 1964 when he ran into legal trouble. In November 1964, he was convicted of "child stealing" when he failed to return the children promptly after a visit. The courts eventually awarded John and Patsy joint custody in September 1965. [23] The former Patsy Battaglia died on March 14, 2017.

The shooting incident in Battaglia's home occurred two days before he was scheduled to appear in federal court over failing to pay tax on $10,584 of unreported gambling income in 1957. [24] Battaglia settled those charges on November 22, 1961, when he was sentenced to two-year probation and fined $2,100. [25]

Although barred from entering Nevada casinos, Battaglia continued to find inventive ways to cheat them from the outside. Battaglia and associate Harold Tenner set up a horse race betting scam to defraud legal bookmakers at Las Vegas gambling establishments. Using a "past post-time scheme," Battaglia obtained race results before the bookmakers and then placed bets on the winning horses, assuring himself of a payday. [26] The scheme netted over $28,000 before anyone caught on. On August 19, 1964, Battaglia was convicted and sentenced to ten years in federal prison.

The case may have compelled Battaglia to cooperate more fully with the FBI. Available FBI intelligence reports show a noticeable uptick in the quality and volume of Intel shared by Battaglia after his conviction. He divulged more about the organization and its activities during this period than in earlier contacts.

His earlier cooperation had been more restrained. For example, on November 29, 1962, fifteen months after Battaglia first agreed to cooperate, federal agents met with him. They stated that he "continued to exhibit a superficially friendly attitude," but furnished no incriminating information about his associates. [27]

Battaglia appealed his horse betting conviction to the United States Supreme Court. On January 3, 1966, the court affirmed the conviction, ordering him to begin serving his sentence. Yet it appears he somehow won a rehearing. A newspaper reported that Battaglia pleaded guilty to wire fraud on October 15, 1968, and was sentenced to five years probation. [28]

No available information explains the apparent rehearing or the dramatic reduction in his sentence. It's unclear if Battaglia's secret cooperation with federal authorities affected the case.

Instead of being grateful that he was not locked up and mending his ways, Battaglia set to work planning the biggest score of his life.

Pfeffer

Jeweler Newton Pfeffer was a respected business and civic leader in Tucson, Arizona. [29] He was the former general manager of the Grunewald and Adams jewelry store chain and had served on Tucson's City Planning and Zoning Commission. In 1965, after thirty years working for others, Pfeffer opened his own high-end jewelry store on the ground floor of the Pioneer International Hotel.

Pfeffer purchased giant advertisements in the local newspapers to attract customers. He obtained his merchandise on consignment from New York City's wholesale diamond houses. The wholesalers entrusted third parties like Pfeffer with diamonds to sell on the understanding that he would pay them after he found a buyer. Pfeffer retained a slice of the sale price as his profit. It was a profession that operated on trust and personal relations.

It's unclear how Pfeffer first met Battaglia, but he was reportedly aware of his underworld reputation. Battaglia saw Pfeffer as a mark from the start. Over time, he gained Pfeffer's confidence by dependably paying cash for several valuable jewelry pieces. In December 1968, Battaglia allegedly persuaded Pfeffer to loan him roughly 150 diamonds worth $1.2 million (retail value of $4.5 million.) [30] One piece, called the Transvaal blue diamond, was valued at $166,130. Actress Elizabeth Taylor expressed an interest in purchasing it. [31]

Battaglia told Pfeffer that he had buyers lined up for the diamonds and that they would profit handsomely from the sales. [32] Pfeffer turned over the diamonds, but weeks went by, and then months, and he heard nothing about their sale. Finally, Pfeffer demanded that Battaglia pay him for the diamonds or return them. Battaglia told him to "forget it." [33]

Pfeffer was left distraught. He could not repay the New York City wholesalers who supplied the diamonds. They froze his ability to work by cutting off his credit. He tried to keep his business afloat by taking out loans from several banks and associates, but it wasn't enough. Pfeffer's reputation, built up over a lifetime, had turned to mud.

John Battaglia

On March 29, 1969, fifty-three-year-old Pfeffer killed himself by leaping off the eleventh floor of the Pioneer International Hotel. His body landed outside the front door of his store. His suicide note accused Battaglia of leaving him in "financial ruin." [34] "Make John Battaglia pay all his life for the way this "mad dog" created a situation for me from which I couldn't extricate myself." [35]

A week before he died, Newton Pfeffer contacted the FBI about the missing diamonds. However, he reportedly withheld details of his arrangement with Battaglia, so the FBI recommended he seek restitution through court action. Pfeffer was more forthcoming in a second interview a few days later but still refused to answer questions put to him by federal agents on his lawyer's advice. The FBI finally opened a criminal investigation after Pfeffer's death.

A grand jury on December 3, 1969, indicted Battaglia on five counts of grand theft. [36] The charge caused Battaglia to be found in violation of his wire fraud probation, and he was immediately sent to the penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington, to serve his five-year suspended prison sentence until the new charges could be adjudicated.

At trial, prosecutors argued that Battaglia acquired Pfeffer's missing diamonds on consignment using the ruse he had legitimate buyers lined up. He then sold them at "ridiculously low prices," far below anything Pfeffer would have agreed to. They believed he was acting as an "agent" for his brother Charles Battaglia, imprisoned at the time for an unrelated offense. [37]

Battaglia's lawyers maintained it was all a big misunderstanding. They admitted that Battaglia had received some diamonds from Pfeffer, but he had paid a fair price. His lawyers produced receipts showing Battaglia paid Pfeffer $70,050. [38] However, they claimed Battaglia had no idea what had happened to the so-called missing diamonds. The defense argued that Pfeffer kept poor accounting records, and his failure to keep better track of his merchandise was the root of the problem. Battaglia did not testify.

The jury accepted Battaglia's defense. He was acquitted on November 13, 1970, after jurors stated the prosecution failed to make the case that he stole any diamonds. However, Battaglia's victory in the courtroom came at the expense of his health. Four weeks into the trial, he suffered a mild heart attack requiring brief hospitalization. [39]

John Battaglia died on December 2, 1971, of a heart attack. A family member found the fifty-two-year-old unconscious in his Sherman Oaks home. An ambulance rushed Battaglia to Los Robles Hospital, where he died. [49]

The FBI had dropped John Battaglia as a confidential informer years earlier, after the Supreme Court in January 1966 upheld his wire fraud conviction. FBI guidelines called for terminating a relationship with an informer convicted of a serious crime. Battaglia had funneled information to federal agents for a period of four and a half years.

The loss of Battaglia did not significantly impair the FBI's intelligence-gathering capabilities. By that time, the Bureau had developed member-informants within the crime families of Los Angeles, San Jose and San Francisco. Those informants could furnish information about the Mafia in California. Federal agents also had three member sources within the Bonanno Crime Family, including Bill Bonanno, supplying Intel about the organization in New York and Arizona.

John Battaglia advised federal agents that his brother Charles was a Los Angeles Crime Family member. Charles was inducted in 1952 by Jack Dragna. After Dragna died of a heart attack in 1956, problems developed between Charles and new boss Frank DeSimone.

Charles Battaglia

The son of former Mafia leader Rosario DeSimone, Frank DeSimone was a low-key attorney who had the misfortune of taking over as the FBI ramped up its investigation into the organization. Fearful of FBI surveillance, he steered the crime family away from risky criminal activity and avoided contact with other mobsters. [40] DeSimone passed orders to his subordinates through intermediaries, infuriating Charles Battaglia and other more aggressive members like Johnny Roselli, whom John Battaglia called a "very cunning and important member." [41] As a Mafia member, Charles Battaglia believed he had the right to interact with the boss directly.

To keep the peace, DeSimone permitted Charles to transfer his Mafia affiliation to the Bonanno Crime Family's faction in Tucson, Arizona. [42] (Joseph and Bill Bonanno formed a branch of the organization in Tucson after moving there for health reasons in the 1940s.) Roselli moved to the Chicago Outfit, where he had close relations with Paul Ricca and Sam Giancana.

Mafiosi occasionally transferred memberships for practical reasons. For example, if a mobster moved out of state, he might transfer to the local crime family rather than remain affiliated with one on the other side of the country. Changing affiliations because of Mafia politics was less common, and in this case showed the seriousness of Battaglia's disenchantment.

John Battaglia advised that his brother Charles was the "leader of the Tucson hoodlum group." However, he downplayed the significance of the group stating there was no "formal organization of La Cosa Nostra in Tucson." [43] (Charles Battaglia tried to transfer back to the Los Angeles Crime Family after Joseph Bonanno lost favor.) [44]

John stated that the Chicago Outfit operated a large bingo game in Tucson with his brother's approval. Battaglia said that Sam Giancana received all the "publicity" in Chicago, but Anthony Accardo was the real boss of the organization.

How Charles Battaglia and Joseph Bonanno met is unknown. Joseph and Bill Bonanno wrote memoirs discussing Battaglia's relationship with the organization but never mentioned who introduced them. Unsubstantiated reports indicated Battaglia operated in Brooklyn, New York, a Bonanno Crime Family stronghold, during the early 1940s.

"Bill" Bonanno

Growing up in Western New York, the Battaglia brothers knew Joseph Bonanno's uncle Stefano Magaddino, who led the regional crime family. The Battaglias' cousin Salvatore Pieri was an influential member of Magaddino's organization. So Magaddino may have put in a good word about Charles Battaglia to Bonanno.

Magaddino and Bonanno fell out in the late 1950s when Bonanno's efforts to expand his territory caused him to step on the toes of other bosses. Whatever good feelings Magaddino might have had for the Battaglia brothers evaporated. Magaddino accused the brothers of "picking fights" with his men. In one instance, an FBI listening device recorded Magaddino insisting that John Battaglia was having an affair with his brother's wife. [45]

No event in the New York underworld in the 1960s preoccupied the FBI more than the intra-family conflict inside the Bonanno Crime Family called the "Banana War." When boss Joseph Bonanno elevated his son Bill Bonanno to a senior position within the crime family, high-ranking members revolted. The Mafia Commission, already predisposed against Joseph Bonanno for his past scheming, encouraged the unhappy Bonanno members to form a rebel faction. A shooting war resulted.

The Banana War lasted four years. Mobsters on both sides were killed. During the conflict, Joseph Bonanno vanished for two years before reappearing unharmed, claiming his uncle Stefano Magaddino kidnapped him. The conflict ended in 1968 when Joseph and Bill Bonanno accepted defeat, retired to Arizona, and a Commission-approved boss took over.

According to the FBI, John Battaglia provided "considerable information" about the Bonanno Crime Family and Joseph Bonanno's mysterious disappearance. [46] As the brother of Bonanno's Arizona representative, John was privy to insider information about the organization. Although most of what he furnished remains classified, he let federal agents in on a secret coup attempt hatched by Bonanno that they knew nothing about.

DeSimone

That coup attempt occurred in California two years before the alleged 1963 plot of Joseph Bonanno and Joseph Magliocco (Profaci/Colombo Crime Family) to assassinate rival New York City bosses Thomas Lucchese and Carlo Gambino.

According to John Battaglia, Bonanno conspired with Johnny Roselli and Joseph Giamonna, a Los Angeles Crime Family member, to depose Frank DeSimone and take over the Los Angeles Crime Family for himself. (Another FBI CI, Frank Bompensiero, suggested that Bonanno wanted to install his son Bill as boss of a unified California family, including Los Angeles, San Jose, and San Francisco.)

Roselli, a Chicago Outfit member by this time, had second thoughts about participating and informed DeSimone about the plot. Roselli and DeSimone met in New York City with Commission member Carlo Gambino to discuss the matter. Afterward, the Commission ordered Bonanno to drop his plans. Battaglia said Bonanno hated Roselli for his betrayal. [47]

In the middle of the Banana War, Joseph Bonanno contacted Sicilian Mafia leaders for help to regain control of his crime family. Battaglia reported that Bonanno, who came from prominent Mafia bloodlines, hoped the Sicilians could use their influence with the American Mafia Commission to swing the outcome his way. Bonanno was desperate for help after alienating the other New York bosses through his plotting and double dealing.

Bonanno's plea was not entirely without precedent. U.S. Mafia leaders had appealed to influential Sicilian underworld figures to arbitrate disputes back in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In that era, Mafia organizations in America maintained close connections with the crime society across the Atlantic. However, the relationship had changed decades before Bonanno made his request. Charles Battaglia reportedly told his brother that the Sicilian Mafia's supervision over U.S. crime families ended about 1930 when the American Mafia became independent and was "granted self-governing rights." [48]

1 "Man cleared of pair of charges," Hollywood Citizen-News, Sept. 12, 1961. p. 22.

2 FBI, Criminal Informants-Criminal Intelligence Program, Washington, D.C., June 21, 1961, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10089.

3 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Philadelphia Office, Sept. 11, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10351.

4 FBI, Louis Thomas Dragna, Los Angeles Office, June 2, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-10220-10441.

5 "California Death Index, 1940-1997." Battaglia's father died six months earlier, Dec. 15, 1960.

6 "Nab Louis Battaglia at airport in Dallas," Los Angeles Evening Mirror News, Jan. 28, 1958, p. 5.

7 "Witnesses balk at testifying," Pomona Progress Bulletin, Nov. 14, 1958, p. 1.

8 "U.S. indicts John Battaglia," Los Angeles Mirror, Sept. 29, 1961, p. 1.

9 "Cohen refuses to talk about income, Lana," Hollywood Citizen-News, Nov. 14, 1958, p. 1-2.

10 "Cohen freed of contempt," San Fernando Valley Times, Nov. 17, 1959, p. 2.

11 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, January 29, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10206-10406.

12 "‘Bat' released on $1,500 bond," Wichita Falls TX Record News, Jan. 30, 1958, p. 12.

13 "Nab Louis Battaglia at airport in Dallas," Los Angeles Evening Mirror News, Jan. 28, 1958, p. 5.

14 "Wichitan gets most of his $10,000 back," Wichita Falls TX Record News, Jan. 29, 1958, p. 1; "Dallas charges Battaglia with narcotics possession," Wichita Falls TX Times, Jan. 30, 1958, p. 4; "Man held in $10,000 fraud," Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Jan. 29, 1958, p. 5.

15 "Casino operators get ‘Black Book' of hoodlums, orders to keep them out," Sacramento Bee, April 3, 1960, p. B8.

16 "Gambler to pay wife $700 monthly," Hollywood Citizen-News, Oct. 17, 1961, p. 17.

17 "Gambler to pay wife $700 monthly," Hollywood Citizen-News, Oct. 17, 1961, p. 17.

18 "LA man indicted in tax case is shot; wife held," Fresno Bee, Oct. 29, 1961, p. B9.

19 "Battaglia shot, wife arrested," Los Angeles Times, Oct. 29, 1961, p. 13.

20 "Police probe shooting of underworld figure," Baltimore Sun, Oct. 30, 1961, p. 3.

21 "Wife is held in shooting of ‘the Bat,'" Waterloo IA Daily Courier, Oct. 30, 1961, p. 2.

22 "Mrs. Battaglia freed in husband shooting," Los Angeles Times, Nov. 2, 1961, p. 8.

23 "Battaglia kids custody to both parents," Hollywood Citizen-News, Sept. 25, 1965, p. 4.

24 "U.S. indicts John Battaglia," Los Angeles Mirror, Sept. 29, 1961, p. 1.

25 "Battaglia fined $2,100 in U.S. tax violation," Los Angeles Times, Nov. 23, 1961, p. 20; "Battaglia fined for tax dodge," Los Angeles Mirror, Nov. 23, 1961, p. 16.

26 "John Battaglia begins prison term in bilking," Salinas Californian, Jan. 4, 1966, p. 11.

27 FBI, Interview Program Criminal Intelligence Matters, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 11, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-9044-10073.

28 Rawlinson, John, "Pfeffer-Battaglia deal aired," Arizona Daily Star, April 9, 1969, Section 2, p. 1.

29 "Pfeffer to open own store in Pioneer," Tucson Daily Citizen, Jan. 1, 1965, p. 8.

30 Green, Dave, "Racketeer linked to suicide: Jeweller Pfeffer faced disaster," Tucson Citizen, April 3, 1969.

31 Rawlinson, John, "'Ransom effort' introduced in Battaglia trial," Arizona Daily Star, Oct. 28, 1970, p. 1.

32 "Tucson death of jeweller tied to Mafia," Arizona Republic, April 5, 1969, p. 21.

33 Rawlinson, John, "Pfeffer-Battaglia deal aired," Arizona Daily Star, April 9, 1969, Section 2, p. 1.

34 "'The Bat' indicted in gem swindle," Redwood City CA Tribune, Dec. 4, 1969, p. 13.

35 "2 named in Pfeffer case: John Battaglia faces 5 counts," Arizona Daily Star, Dec. 4, 1969, p. 1.

36 "'The Bat' indicted in gem swindle," Redwood City CA Tribune, Dec. 4, 1969, p. 13.

37 Rawlinson, John, "Battaglia name comes to fore in Pfeffer case," Arizona Daily Star, April 5, 1969, p. 1.

38 "Battaglia accused of gem sales below cost," Los Angeles Times, Nov. 11, 1970. Part II, p. 10.

39 Villasenor, Rudy, "Battaglia goes to hospital; trial delayed," Los Angeles Times, Nov. 3, 1970, Part II, p. 2.

40 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Sept. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10328.

41 FBI, Johnny Roselli, Los Angeles Office, Dec. 21, 1964, NARA Record No. 124-10215-10222.

42 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Sept. 26, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10290-10437.

43 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Phoenix Office, May 7, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10426.

44 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, Oct. 4, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10293.

45 FBI, Steve Magaddino, Buffalo Office, March 31, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-1024-10421.

46 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Los Angeles Office, May 12, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10204-10433.

47 FBI, Johnny Roselli, Los Angeles Office, March 5, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10218-10335.

48 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Memorandum Mr. Gale to Mr. Belmont, Jan. 7, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10339.

49 "John Battaglia, alleged crime figure, dies," Santa Cruz Sentinel, Dec 3, 1971, p. 26.

50 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Memorandum Mr. Gale to Mr. Belmont, Jan. 7, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10339.

51 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Memorandum Mr. Gale to Mr. Belmont, Jan. 7, 1965, NARA Record No. 124-10223-10339.

52 FBI, U.S. House Select Committee On Intelligence Activities, FBI Director To The Attorney General, Dec. 12, 1975, 124-10274-10041.

53 FBI, U.S. House Select Committee On Intelligence Activities, FBI Director To The Attorney General, Dec. 12, 1975, 124-10274-10041.

54 FBI, U.S. House Select Committee On Intelligence Activities, FBI Director To The Attorney General, Dec. 12, 1975, 124-10274-10041.