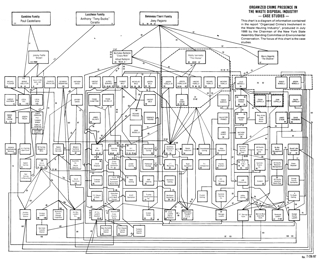

Web Editor's note: This report was based on testimony received by the New York State Assembly Environmental Conservation Committee in 1984. The report was compiled in 1986 and released in 1987. Excerpts were first presented on this website around 2010, with additions and formatting put in place in 2015. The web document was expanded and reformatted in 2021. Efforts have been made to preserve the look and feel of the report's original page formatting. The report's 1987 fold-out chart of business-underworld relationships has been reproduced as a PNG image.

"What are criminal gangs but petty kingdoms?

"A gang is a group of men under the command of a leader, bound by a compact of association, in which the plunder is divided according to an agreed convention. If this villainy wins so many recruits that it acquires territory, establishes a base, captures cities and subdues people, it then openly arrogates to itself the title of kingdom, which is conferred on it in the eyes of the world, not by the renouncement of aggression but by the attainment of impunity."

-- The City of God

Saint Augustine (c. 214 A.D.)

( blank )

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special acknowledgement is due the following for their contributions to this report:

Robert Fisher (intern) for his assistance in preparing the reference section;

Bonnie MacLeod for her work on the project until she left in September 1985;

And Robert Terry Logan who, as Publications Coordinator, provided enormous help in reissuing this report in its present format.

MAURICE HINCHEY, Chairman

Assembly Environmental Conservation Committee

July 15, 1987

( blank )

FOREWORD

The New York State Assembly Environmental Conservation Committee has long been concerned with the growing threat to the environment caused by the illegal disposal of hazardous and solid wastes. It has also noted that an ironic consequence of the development of environmental laws to control pollution has been the creation of a new era of opportunity for those who do not demur at criminal behavior if it guarantees easy profits. There is a substantial body of evidence that organized crime controls much of the solid waste disposal industry in New York State and elsewhere. There is also evidence that the criminal activity is not confined entirely to organized crime, but is also engaged in by other unscrupulous entrepreneurs; and that there have also been instances of multinational corporations not hesitating to jeopardize public health and safety.

Official documents are available, including the congressional hearings on Organized Crime Links to the Waste Disposal Industry, held in 1980 and 1981, which suggest the extent to which organized crime has become imbedded in the waste disposal industry.

Much earlier, of course, there were the United States Senate Committee Hearings under Senator John McClellan in 1957, which probed deeply into the extent of criminal infiltration of the garbage disposal industry. In 1981 a New York State Assembly task force held a public hearing that raised some important questions. The State Senate Select Committee on Crime, under the chairmanship of Senator Ralph Marino, has also done productive probing.

In the fall of 1984, the Assembly Environmental Conservation Committee held its own hearings on the subject, recognizing that more needed to be done, both in the way of enforcement and new legislative initiatives, if the problem is to be brought effectively under control.

As our hearings progressed we came to realize the need for a systematic summarization of the accumulated information that had been gathered over the years -- not only through official investigations (our own as well as those of others) but through the diligence of the news media. Even more important, in our minds, was the need to analyze the sprawling mass of data and disentangle the essential from the nonessential. The objective has been to produce an accurate assessment of the waste disposal industry and the extend of criminal activity within it, as well as to discuss policy alternatives needed to correct the problems.

In the course of preparing this report a wide range of activities in the waste hauling industry were investigated by this committee over a period of nearly two years. In order to focus public attention on the problem we have narrowed the discussion to those case histories that best illustrate the kinds of problems that need correction. The focus is on New York City, Long Island and the Mid-Hudson Valley.

Each study section of this report illustrates one or more of the key aspects of the hazardous and solid waste disposal problem as it affects New York State. At the end of each section there is a staff review of the case history discussed.

While it is hoped that the report will be of particular usefulness to those who are experts in the field, we have also tried to make it readily accessible to the general reader by providing essential definitions and background information.

Because some of those using this report will appreciate further information than contained in the text, we have tried to be generous in the use of references so that those who wish can trace the complex web of interrelationships beyond the boundaries of the situations described. Unscrambling the elements in a business conspiracy can be similar to solving a jigsaw puzzle, and one never knows when an apparently irrelevant piece of information can suddenly complete the picture for those who already have other parts of the puzzle.

In this connection the fold-out chart included with the report should be invaluable to those who are interested in tracing the interrelationships of the various companies and individuals, some of whom, at one time of another, were found guilty of violations of the Environmental Conservation Law (ECL) and other laws. The chart should, of course, be used in conjunction with the text.

Appendix A and Appendix B provide important background materials. Appendix A contains what is hoped will be a useful compendium of the environmental enforcement tools now available for combatting the problem of illegal disposal of solid and hazardous wastes. Appendix B provides a glossary of many of the terms most frequently referred to in the literature on this subject. For the convenience of the reader, subjects receiving further discussion in the appendices are marked with an asterisk (*) the first time they occur in the text.

A summary report, to be released at a later date, will expand on suggestions contained in this report and will include legislative proposals for dealing with the problem.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS cont.

CRIMINAL INFILTRATION OF THE HAZARDOUS

AND SOLID WASTE DISPOSAL INDUSTRY

IN NEW YORK STATE

There is overwhelming evidence, accumulated over the past 30 years, that organized crime is a dominating presence in the solid waste disposal industry in New York State as well as other parts of the country. However, there is some disagreement as to the extent to which organized crime has infiltrated the hazardous waste hauling industry.

A principal purpose of this report was to investigate the extent to which organized crime controls the waste hauling industry in New York State. It carries forward the findings of the 1980 House of Representatives hearing on the involvement of organized crime in the hazardous waste disposal industry in New Jersey and demonstrates that organized crime's activities since then have not abated but actually increased, despite governments increasing concern over the threats to the health and safety of the public posed by such activities.

In the fall of 1984 this committee's hearings, held in New York City and Goshen, New York, made it clear that organized crime was seeking to increase its grip on the hazardous as well as solid waste hauling industry in New York State by extending its activities beyond its traditional strongholds in metropolitan New York, Long Island and Westchester into the Mid-Hudson region and beyond.

This report presents an overview of the situation as it exists today, reviews the effectiveness of existing legislation and evaluates the performance of those agencies entrusted with the responsibility for seeing to it that the laws are obeyed and that public health and safety are not jeopardized. It also provides a basis for developing appropriate recommendations for resolving the problem.

No matter what industry organized crime infiltrates, it not only threatens the integrity of that industry but it inflicts economic loss on society and tends to corrupt it. Organized crime has played a role in many industries -- gambling, banking, clothing, trucking, dry cleaning, cutlery sharpening, restaurant and bar businesses, real estate, meat packing, kosher food products, and vending machines -- to mention only a few. Through its involvement in almost all of these activities there runs the common thread of intimidation, violence and even murder.

The devastating effect organized crime's involvement in the solid and hazardous waste hauling industry can have on the environment is only one part of the problem. The other part is the threat to society contained in its ruthless methods and the economic waste it causes through its restraint of trade, price-gouging and bid-rigging practices.

In dealing with organized crime's involvement in the solid and hazardous waste hauling businesses, this committee has had to consider the effectiveness of current laws

and regulations in meeting today's increasingly stringent environmental standards. That is an important part of our responsibility. But we also have had to consider the pernicious influence organized crime figures can exert simply by being involved in the industry, even if in some instances they abide by existing environmental regulations. This report documents both aspects of the problem.

Environmental pollution was not created by organized crime. The story of pollution involves many villains, but a considerable amount of the environmental damage that has been done to our planet is simply the result of ignorant, underregulated or careless industrial activity. Much of the environmental crime about which we are concerned today was not a crime 30 years ago; and even the most sophisticated of us sometimes wince to think of what we once considered environmentally acceptable.

The rising stream of dangerous industrial wastes brought on by the rapid development of industrial technology in the latter half of the 19th century had already reached flood proportions by the end of World War II, when the United States was producing one billion pounds of such wastes each year. But less than 40 years later that amount seemed insignificant when compared with the 125 billion pounds being added to the hazardous waste stream in 1980.

Among the over 50,000 substances listed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as posing a potential hazard to human health are some of the most dangerous chemicals known to man. They can produce cancers, birth defects and genetic changes in animals and humans, as well as acute poisoning and a variety of respiratory, genitourinary and skin disorders.

The threat to America's health posed by the leaching of toxic and hazardous wastes from a conservatively estimated 75,000 industrial and 15,000 municipal landfills cannot be easily dismissed. Such leachates have already contaminated public and private water supplies throughout the nation. And once an underground aquifer becomes polluted it is often virtually impossible to undo the damage. Such wastes can eventually enter the food chain, first by being absorbed by plants and animals, and finally affecting humans; or by direct contact with humans, as at Love Canal, where the chemical wastes produced as a result of World War II seeped years later into the homes of a residential community, creating a human crisis that shocked the nation.

These dangerous wastes are part of the price we are paying for the rapid development of industrial technology over the past 100 years. Fortunately, a concurrent increase in the sophistication of our scientific procedures has enabled us to detect healththreatening causal relationships that in a more innocent time went undetected. The industries and chemical companies, which have been largely responsible for the contamination, contend that it is only with the benefit of hindsight that we can criticize them for the immense problems to which they unwittingly contributed. There is some truth in this. As a society, we are not only in the process of compiling a new body of law, we are also defining whole new areas of environmental crime. Nevertheless, many of these industries had long been aware of the dangers their manufacturing operations posed, and some of them deliberately withhold information from the health authorities and related law enforcement agencies. In some cases the United States government was party to the deception.

The development of legislation to contain the threat from environmental pollution has not been as fast as many 'would have liked, but it will be worthwhile to review the extent of the change in public attitudes over the past 20 years.

It is hard to believe today that it was not until the 1970s that hazardous wastes were officially recognized as a health or environmental problem in this country. The 1970 Report of the Council on Environmental Quality contained no mention of hazardous wastes, nor did the federal EPA, which came into being that same year, make any reference to it. Congress had passed the Solid Waste Disposal Act in 1965, but this was concerned basically with funding for planning and research. It was not until 1976 that the Toxic Substance Control Act was passed, which allowed the federal government to regulate the manufacture and distribution of new chemicals that have a potential to harm the environment or public health. The agency was given the authority to prohibit the use of chemicals suspected or proved to be dangerous and to regulate the thousands of chemicals already in use, as well as prevent the introduction of new substances if they were shown to be dangerous.

About the same time that Congress passed the Toxic Substance Control Act it also developed standards for air quality. When the 1970 Clean Air Act was passed by Congress, New York State's Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), created that same year, was given the responsibility of seeing that this State met federal standards.

It was not until 1976 that the federal government enacted the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA*), which addressed, among other things, the regulation of hazardous waste management. Its provisions allowed the EPA to authorize states to conduct hazardous waste regulatory programs equivalent to the federal program. However, the important manifest system, which was part of RCRA, was not put in place until 1980.

New York State had enacted legislation that permitted DEC to issue regulations regarding refuse disposal and municipal incinerators as early as September 1973. These regulations were revised in 1978 and again in 1981, 1982 and 1985 in a manner consistent with changes made in federal regulations.

The federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA*), commonly known as the Superfund, was also passed in 1980 to pay for the costs of cleaning up releases of hazardous substances.

However, these federal statutes have not been rigorously enforced, particularly under the Reagan Administration.

In Appendix A there will be found summaries of the various pertinent federal and New York State initiatives.

*For further comments see appendix.

Historically, industry has not played a leadership role in protecting the environment. Even after more than a century of intense debate on the subject, it still is reluctant to undertake additional environmental precautions unless it views the evidence as overwhelming that such precautions are necessary. This reluctance has been expressed in many ways:

- Failure to report known instances of pollution;

- Protracted legal actions to delay implementation of new laws;

- Lobbying campaigns against proposed legislation;

- Refusal to cooperate with enforcement agencies.

Despite this reluctance, however, most large corporations generally express their resistance in lawful ways, and in some instances they have actually taken the lead in developing environmentally desirable changes in the way their industries operate. Very often it is the marginal firms, seeking to eke out a profit, that are more likely to take the risks involved in breaking the law.

Huge, multinational corporations are, however, sometimes far wealthier than some of the countries in which they operate, and their ability to break the law with impunity and corrupt the political process has been frequently noted. Even during the few short months during which this report was being prepared several glaring examples of corporate misconduct were subject to media attention. Hardly a week goes by without the financial pages of the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal carrying at least one story about another instance of corporate criminal activity. Some of these activities are commonly thought of as being exclusively the province of organized crime, but that, unfortunately, is not the case. The recent admission by chicken tycoon, Frank Perdue, that he sought the help of the organized crime boss Paul Castellano, [1] who was murdered gangland fashion in 1985, warns us of the darker aspects corporate activity sometimes can take on. On the other hand, Consolidated Edison's determination not to acquiesce in a "property rights"* contract sought by an organized crime carting company (see page 53) displays the kind of integrity that is welcome in an American corporation.

There is another class of individuals, moreover, for whom risk-taking is particularly attractive wherever a potential for great profits exists. One such entrepreneur was Russell Mahler, who was sentenced to six months in prison and five years probation and ordered to pay New York City over $500,000 in restitution, as well as a fine of $10,000. He began his career as a waste-oil scavenger, operating within the law. He ended it convicted in three states of crimes that may have endangered the health and safety of millions of people and that ravaged the environment all along the Eastern seaboard. His activities, which are described in detail in this report, were not, so far as has been discovered, linked to organized crime families. In any case, he was able to see the possibility of quick and easy profits in an area where the rules were not fully developed and also not adequately enforced.

The section beginning on on page 11 (The Structure of Racketeering) provides a benchmark for testing the several case histories included in this report. It is

based on various studies that have been made on organized crime, including the recent hearings of the Presidents Commission on Organized Crime.

Organized crime continues to dominate the waste hauling industry, not only in metropolitan New York, Long Island and Westchester, but has increased its operations in Rockland, Orange, Putnam and Dutchess counties. Those communities are now being confronted with the burden of shouldering the enormous, increasing social and economic costs exacted by racketeering. New inroads are being made into Ulster, Columbia and Greene counties.

CONTRIBUTING TO THE SUCCESS OF ORGANIZED CRIME'S TAKEOVER OF THE WASTE HAULING INDUSTRY?

Organized crime has infiltrated a wide variety of legitimate businesses, but the waste hauling industry is particularly susceptible to the tactics that organized crime employs. Moreover, the fact that the individual carting concerns were originally small, family operations, largely of the same ethnic origins, closely knit and struggling to make a living in an occupation that was looked down on by the general public, made it easy for them to accept the "property rights" system as a means of protecting their livelihood.

When the nation began to become more sensitive to environmental issues in the 1970s and laws were enacted to curb the indiscriminate dumping of toxic and hazardous wastes, it was natural for solid waste haulers to become involved in this business also. Unfortunately, the opportunities for windfall profits by disposing of the wastes illegally created new opportunities for organized crime. It also provided them with the added advantages that go with monopoly control, not only through domination of the carting of the wastes, but also through ownership and operation of the waste disposal facilities.

Government has not been inactive. Much new legislation has been enacted at both the state and federal levels, but the new laws are not completely adequate because they were designed to fit a social context in which the lawbreaker is the exception rather than the rule. What was not recognized is that a conspiracy was already in place that, if left unchallenged, could effectively destroy the nation's efforts to solve the solid and hazardous waste disposal problem. The facts and interrelationships disclosed in the accompanying report suggest strongly that there already exists an organized crime network, if not directed by one individual or family, at least sufficiently coordinated so that the network functions as a classical conspiracy.

This conspiracy has now become so basic a functional part of the waste hauling industry that it will not be uprooted unless, first, the public is taught to recognize the pervasiveness and seriousness of the problem, and secondly, government is prepared to make the necessary commitment in terms of funding and effective laws and regulations.

Wherever there are governmental regulations there never will be sufficient resources to guarantee 100 percent compliance with those regulations. However, the right combination of programs, by changing society's basic attitudes, can deprive criminal activity of the permissive climate in which it so readily flourishes.

That combination of programs should include:

- A system of inspection and controls within the industry that compels accountability of requiring adequate documentation of activities.

- Adequate funding and staffing of the regulating agencies to ensure reasonable monitoring capability.

- A system of fines and penalties sufficient to discourage "bad actors."

- A permitting system that provides the opportunity to eliminate from the industry those found guilty of criminal practices in connection with the industry.

- An educational and public relations program that creates a social climate where the public will be disinclined to tolerate violations.

These programs will be discussed in detail and placed in public policy perspective in a subsequent volume dealing with recommendations.

LA COSA NOSTRA (LCN) IN A NUTSHELL

"La Cosa Nostra, which in Italian means 'Our thing,' is an association of criminals joined together to carry out illegal pursuits. The term was first brought to the public's attention in 1963 when Joseph Valachi, a government informant who had been a member of the New York LCN family headed by Vito Genovese, testified before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

"La Cosa Nostra families are run in an hierarchical manner. Each family is controlled by a 'boss,' who is assisted by an 'underboss,' and advised by a 'consiglieri.' The next level down is that of the 'caporegime.' Each boss has under his control a number of 'capos' or lieutenants, the number of these depending on the size of the family. Each capo controls a 'regime' consisting of inducted or 'made' members of the family. These members are referred to a 'soldate,' 'soldier,' or 'buttons.' A member of a family is sometimes referred to as a 'wise guy' or a 'made' man. Made men frequently have non-members working for or with them. 'Associate' is the term law enforcement uses to identify a person who, while not an LCN member, works closely with the family. LCN members are males of Italian ancestry. Associates may be of any race, color, creed, or national origin.

"The hierarchical structure of the LCN families has led some observers to place unwarranted stress on the organization of these groups as if they were highly formalized military commands. In fact, LCN families are not as formal as supposed. With a given family, for example, a certain capo may not enjoy as much respect or exercise as much influence as a lower ranking member. Similarly, law enforcement experts point out, the ability to generate money for the family--that quality which causes his peers to view him as an 'earner'--is considered an important measure of the status of a member. An associate who is felt to be a good earner may also enjoy considerable respect and influence." [2]

--Profile of Organized Crime: Mid-Atlantic Region,

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations,

United States Senate

SNATCHES OF CONVERSATION

IN A BUGGED JAGUAR

(From tapes quoted in The President's Crime Commission Report) [3]

Salvatore Avellino, "made" LCN member, chauffeur to Anthony Corallo, boss of the Lucchese Crime family, as he detects their car is being tailed by law enforcement: They're right behind us now, they figure you running some big, big enterprises right now. That's what it is. You know, with the garbage, and with an . . . and with the incinerators now, and ah . . . with all that shit. Incineration is big thing with us, the thing of the future. They figure that you got it, you control it.

Corallo: They're right, you know.

Avellino to Richard DeLuca, Lucchese Crime family member: He's telling me that the union is his, you know. So I'm saying: what do you mean, the union is yours? He believes the fucking union is his, and what am I gonna--you know--I'm gonna say: the union, nothing, is yours. Everything is the boss and we only got the privilege of working it or running it, unless you got a, something that is a legitimate thing, you know, that it's yours, then they say: well, that's yours, but anything that's got to do. . . .

DeLuca: You operate at his pleasure. . . . A lot of guys forget that.

Avellino: I mean, I know Salem [Carting] is mine in stock, but I gave--I signed my life to you.

DeLuca: Yeah.

Avellino: 50 really, if I sign my life to you, my stock is yours, but because you're kind enough that you don't make a demand on me.

Avellino in a conversation with Emedio Pazzini, associate of Avellino and owner of Jamaica Ash and Rubbish Removal.

Fazzini: You've got to control the men. That's the power.

Avellino: That's the power.

Fazzini: You gotta control the workers [inaudible] right now you control the employers.

Avellino: Right. Right now we as the Association, we control the bosses, right. Now, when we control the men, we control the bosses even better, now because they're even more fuckin' afraid. Right.

Fazzini: Sal, please don't let my men walk backwards. Let them walk ahead.

Avellino: Do you understand me? Now, when you got a guy that steps out of line and this and that now you got the whip. You got the fuckin' whip. This is what he tells me all the time: "A strong union makes money for everybody, including the wise guys." The wise guys even make more money with a strong union.

( blank )

THE STRUCTURE OF RACKETEERING IN THE

SOLID AND HAZARDOUS WASTE HAULING INDUSTRY

Just as a traveler understands better the country he is visiting by learning in advance something of the customs and practices of its people, so the reader of the following case studies of criminal activities in the solid and hazardous waste hauling business should benefit from a preliminary review of organized crime's modus operandi.

Fortunately, the many studies that have been made on organized crime, including the recent hearings of the Presidents Commission on Organized Crime, provide the basis for a fairly precise profile that can be used as a benchmark for testing the several case histories presented in this report.

Although this profile is based on La Cosa Nostra (LCN)--the specific group subject to scrutiny in this report--many of the characteristics are shared by other organized crime groups active in the United States, the activities of which are not as well known to the general public because they are smaller in scope and have received less media attention. There are regional gangs operating in various sections of the country where the dominant membership may be black, Jewish, German, Polish, Dutch, Lebanese, Mexican or South American, depending on the ethnic background of the particular region. There are also branches of Asian-based gangs, such the Japanese Yakuza and the Chinese Triad Societies, which have become increasingly active in this country in recent years, particularly in the area of illegal drug traffic.

Describing a Triad Society, James Harmon, Executive Director of the President's Commission on Organized Crime, suggested that it be thought of as roughly equivalent to a Mafia family. "It does have some variations in structure, but it is comparable and equivalent to what people generally think of as the Mafia family. It does have a hierarchy, it does have a way to discipline, it does have a way to share profits and allocate responsibility and territories and it does have a way to dissolve disputes among and between various Triad Societies."

Identifying Characteristics of La Cosa Nostra

The typical LCN crime family is not rigidly organized. Members, whether "soldiers" or "capos," can go into and manage their own legitimate businesses; and what they earn in this manner belongs to them and not to the mob. Moreover, at the death of such individuals, the business can be inherited by their children without the syndicate sharing in the estate. However, the syndicate does get its "take" in whatever illegitimate activities the individual is involved, as well as from some of his legitimate businesses if they have been financed by the crime family; and at his death the syndicate decides whether the operation passes on to a blood relative or to another crime family member. In many cases, moreover, the syndicate has provided the bankroll that allowed the member to set up his illegal operations.

The typical LCN family avoids bookkeeping in its operations, relying instead on the use of people it can trust. The penalty for cheating is death and it is carried out ruthlessly, without appeal.

Because of the huge amounts of cash generated by their illegal operations, the syndicate uses "front" or "straw" men whom they can set up in legitimate businesses.

Profits from these operations are "skimmed" by the syndicate and the business itself always remains effectively under the syndicate's control. This is done by having one of their own people work within the operation, perhaps as a manager, secretary or treasurer. Although the straw man may have no criminal record and no previous organized crime connections, the presence of a known organized crime member in his organization should send an immediate signal to law enforcement agencies.

Disputes between crime families can lead to gang warfare, but the more frequent solution is to go to arbitration through a "sitdown"* or a commission set up by the families for that purpose. A crime family moving into a new territory frequently will seek permission to operate from the crime family or families dominant in the area, even though the operation is not of the same nature as those in which the resident crime families are involved. Normally, they would not seek permission if their activity were going to conflict with operations controlled by the resident crime family or families. Territorial rights are basic to LCN family activities, and unless these rights are addressed gang warfare is a likely consequence.

Since the basis of the syndicate's power is its illicit operations, and since it can have no recourse to the legal system of society when differences arise, a very high premium is put on respect for the property rights system. This same system not only applies to the activities of the families but to the individual members within the families.

Examining the solid waste hauling industry, one finds that the property rights system is rigidly enforced. Rebel carters, who will not abide by the system, face intimidation, violence and, as a last resort, murder.

The strategy by which the LCN compels compliance with the property rights system includes the following:

1. It develops and obtains control of waste trade associations, the membership of which is made up of the waste haulers operating in the area. Through the association it is able to dictate the price that the haulers will receive for their services. And it uses the property rights principle to prevent the customers from switching to another hauler to obtain better terms. The haulers are assured of a given territory in which to operate and are able to obtain higher prices for their services through bid-rigging. There is, of course, a kickback to the syndicate.

2. It also develops and/or infiltrates the union that supplies the haulers with their workers. Through the union it can exercise control over the customers and the haulers through the ability to call strikes. Waste hauling is an industry particularly vulnerable to strikes. An uncooperative supermarket chain, for example, can be brought to its knees very quickly if the union refuses to pick up its trash. Similarly, a hauler who violates the property rights system or balks at the payoff that goes to the syndicate will find that his own union workers are suddenly striking against him; or the syndicate has authorized another carting company to cut into his territory at lower rates, possibly only because the other carter has a sweetheart deal that allows him to pay less than union wages, despite the fact that he employs union workers.

3. It seeks to corrupt law enforcement officers and public officials with bribes, payoffs and even intimidation. Mob money and mob influence has played a role in the elections of public officials, has even been said to have played a role in the election of a president. In World War II mob assistance was sought and obtained in assuring a successful beachhead in Sicily. In New York State, when Anthony Scotto, subsequently convicted for racketeering, was on trial, Governor Hugh Carey, three now ex-mayors of New York--"Abe" Beame, Robert Wagner and John Lindsay--as well as labor leader Lane Kirkland, were among those appearing as character witnesses for him.

4. It is prepared to use economic reprisal, threats, violence and even murder to achieve its ends. In recent years it has had to resort to violence less frequently than in the past, but this is only because its reputation for wanton cruelty has become so widely known that the mere knowledge that the mob is behind a particular enterprise is sufficient to terrorize the average businessman or private citizen into compliance.

Such, in broadest outline, is the profile of organized crime's methods of operation. The case histories that follow cannot in every instance cite conclusive proof of organized crime's .involvement, but if the profile offered here is used as a benchmark, it should provide highly reliable insights into which operations are, indeed, apparently connected with organized crime.

Suggested Background Materials

The Mafia or LCN has now entered the folklore of our culture. Any six-year-old who watches TV has some familiarity with the way the mob operates. Inevitably, the public's conception of criminal activities suffers from oversimplification, as, indeed, do some of the statements made by law enforcement officials.

The outline of the Structure of Racketeering in the Solid and Hazardous Waste Hauling Industry presented above has been based on several outside sources, as well as this committee's own investigations.

The investigation of improper activities in the labor or management field, which resulted in hearings before the select committee under the chairmanship of U.S. Senator John McClellan in 1957, provided insight into the racketeering that was taking place in the solid waste hauling industry in the United States. These hearings are of particular importance in understanding the situation in New York City, Long Island and the Westchester area. What makes them even more remarkable is that today, 30 years later, the crime families and some of the same individuals named at those hearings, and their progeny, are still in operation.

It was, of course, Joseph Valachi's testimony before a United States Senate committee in 1963 that revealed for the first time the broad organizational structure and nationwide membership of the LCN.

The Presidents Commission on Organized Crime, which has been holding hearings since 1984 and just released its final report in March 1986, has also provided important information on organized crime activities at the present time.

In between there have been several important hearings by the New York and New Jersey state legislatures that have focused specifically on the solid and hazardous waste hauling industries.

For those who are interested in further information on the matters referred to in connection with the LCN's ability to corrupt and intimidate political figures, the section on Nick Rattenni and the City of Yonkers provides some local examples. The section dealing with John Fine's investigations and the Ramapo landfill is also illustrative. Charles "Lucky" Luciano's participation in World War II on two occasions--once to end sabotage on New York's docks, and later to ease an allied landing at Palermo, Sicily--have been mentioned before in the media. Similarly, with regard to the mob's assistance in securing the Chicago vote for John F. Kennedy in the presidential election as well as the allegations of their involvement in his assassination. Nor should the plot to murder Fidel Castro, through mob agents, be forgotten. Closer to home, the corruption of political figures in .Long Island, both Democratic and Republican, is discussed in Sections Ten and Eleven. In one instance, a state legislator, brother of a U.S. senator, does not come out untainted.

HAROLD KAUFMAN:

PORTRAIT OF AN INFORMER

It is safe to say that Harold Kaufman has probably been one of the most productive and reliable witnesses law enforcement agencies have ever had in tracing the influence of organized crime in the solid and hazardous waste hauling industry.

Harold Kaufman was, by way of analogy, like the stub of a Christmas tree. I had the boughs. I had the tinsel. And I had the tree balls. But I could not hang the tree because I did not have the unifying element, and Kaufman was the person inside the trade association that could . . . in effect, pull the whole thing together for me. [5]

--Steven Madonna, Deputy Attorney General,

Chief of Environmental Prosecution,

New Jersey Attorney Generals Office

Harold Kaufman, describing his activities:

In 1972 I became an administrative assistant to the president of the Sanitation Union, Local 813, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in New York City, which is the union that represents the private sanitation industry in the five boroughs, Westchester, Nassau and Suffolk counties. . . . I became an informant for the FBI in 1978. . . . My job was to continue in the garbage industry, to tape grievance meetings, and to inform them of all the possible organized crime involvement in the waste industry. . . . The solid waste industry is completely controlled by the five families of New York City, and upstate is controlled by Joey Pagano. Dutchess County Santitation was a company that was owned by the Fiorillo brothers, Mattie 'The Horse' lanniello, and Ben Cohen. The Mongellis control the lower part of the counties, around Monroe, Sullivan and Ulster, all the way to Port Jervis. . . . As for toxic wastes, I can't say that all toxic wastes are controlled by organized crime, but through conglomerates, SCA, Browning and Ferris Industries, organized crime figures, who through their connections in the solid waste industry, have moved strongly into it. [6]

Chairman Hinchey: Do you believe what he says, is he a trustworthy person, is he telling the truth?

Mr. Madonna:I never had any difficulty with anything Mr. Kaufman has said. I have been working in the solid waste industry and more recently the hazardous waste industry, and he had a unique opportunity to make insights. To put it bluntly, nuns don't testify about what goes on in a whorehouse. I mean, you need to deal with a whore, and I don't mean to say that as a characterization of Harold, but you have to get somebody who is in with the criminal to get testimony of what goes on. I mean, you just can't look at a professor or a proest, or whoever you may consider a person whose credibility is beyond reproach... I never had any problem with the testimony he gave me.[7]

-- Steven Madonna, Deputy Attorney General,

Chief of Environmental Prosecution,

New Jersey Attorney General's Office

SECTION ONE

THE YONKERS STORY:

MOB PRESSURE ON LOCAL GOVERNMENT

"The City on the Hill Where Nothing is on the Level"

Leading Westchester civic figures and businessmen at the Willow Ridge Country Club knew who he was - the short and stocky elderly man who was out there on the golf course whenever the weather permitted, indulging in his passion for the sport. If they had any misgivings, they kept them to themselves.[8] Nicholas A. Rattenni was not only the father of Alfred ("Nick Jr.") Rattenni, club champion at Willow Ridge, but a man of formidable reputation, a survivor of many gang wars, one of the targets in the famous 1957 McClellan investigation of organized crime, a ruling lieutenant in the Genovese crime family and the czar of the Westchester carting industry, controlling 90 percent of the county's private garbage hauling operations.[9]

Although the circumstances surrounding the elder Rattenni's rise to power occurred some 30 years ago, they are important to an understanding of the process by which organized crime extended its control of the solid waste hauling business in the Hudson Valley. The elder Rattenni died in 1982, but the network of firms controlling the carting business continues. In subsequent sections the activities of Nick Jr., Benjamin Cohen, Russell Mahler, the Milos, Alfred DeMarco, the Mongellis, the Coppolas, the Fiorillos, Carmine Franco, the Gaess brothers and others - all of whom are reviewed in some detail - will be better understood through an understanding of what happened in the City of Yonkers.

Known as a ruthless mob boss in his earlier years, by the time he died in 1982 he had acquired millions from his network of legitimate and illegitimate business operations, including loansharking and gambling, as well as his control of most of the commercial and industrial waste hauling in Yonkers and Westchester.[10]

He served his first prison sentence in 1927, receiving five years in Sing Sing for second-degree robbery. In 1936 he was tried unsuccessfully for grand larcency, and in the 1950s for income tax evasion. In 1970-71 he was a defendant in three separate cases. First, he was acquitted of a charge, of conspiring to bribe Internal Revenue Service employees, but was subsequently found guilty of tampering with that jury. A second case involved him and four State Troopers along with six other persons in a $650 million organized crime gambling syndicate in Westchester and Rockland counties. He was found guilty of conspiracy in connection with providing free vacations to the Troopers in return for protection of the gambling operations. He was acquitted in a third case involving loansharking activities and alleged threats of violence, but nevertheless spent five years in prison for his convictions in the first two cases.[11]

The interest in Rattenni's activities extends beyond his ownership of the two carting concerns, Westchester Carting Corporation and Fleetwood Haulage Corporation. We are also interested in his reputation as a dominant force in the carting industry in Westchester County and his role as an arbiter, settling disputes among the smaller carters.[12] Moreover, the charge made by Harold Kaufman, that Rattenni's son, Alfred Nick Jr., the former Willow Ridge Country Club champion, today plays an important role in the organized crime hierarchy in the Hudson Valley, has to be taken seriously (see page 30). Kaufman's testimony has time and time again been supported by independent investigations of law enforcement agencies.

The elder Rattenni's emergence as czar of the Westchester carting industry began in 1949 when the Yonkers Common Council passed an ordinance that the city would no longer provide garbage collection for commercial and industrial establishments.[13] This, the most lucrative part of the hauling business, would be turned over to private carters. New York City had set the pattern as far back as the turn of the century, opening the door for the strong-arm tactics that were to become the trademark of mob-controlled garbage hauling.

Employees in Rattenni's Westchester Carting Company had approached Local 456 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters to organize them, but one of Rattenni's partners intervened and arranged the signing of a contract with Teamsters Local 27 out of New York City, a local with established underworld connections. Local 27 was not a carting union but one that dealt with the paper and box industry.[14]

When a turf dispute erupted between the two unions, an agreement was eventually reached, allowing Local 27 to keep Westchester Carting, but allocating organizing of future carters to Local 456. The agreement did not last long, however, as Local 27 splintered, spawning Local 813, to handle carters specifically, under the direction of Bernie Adelstein, a business agent for Local 27, who had become heavily involved in Westchester Carting.[15] Adelstein was still active as recently as 1985 and will be referred to again in the section of this report dealing with union corruption in Long Island.

In the meantime, another hauler, Rex Carting, was becoming successful in attracting new customers and had the support of the Yonker's Chamber of Commerce, which had been dissatified with the high cost of doing business with Rattenni's company. Local 813 retaliated with threats and intimidation of customers, and in 1952 Johnny Acropolis, who ran Rex Carting, was shot in the head at point-blank range as he entered his home. A month later Rex Carting went out of business, leaving Rattenni with a monopoly of the carting industry in Westchester County.[16]

The following year Local 813 relinquished its jurisdiction over the county and Westchester Carting installed its own union at the suggestion of "Joey Surprise" Feola of Mamaroneck. Feola, an ex-convict and reputed member of the Genovese family, was later to disappear after a property rights dispute over the garbage removal contract for the Ford Motor Company plant in Mahwah, New Jersey. When wiretaps revealed that Feola's body had been disposed of in a garbage compactor, then U.S. District Attorney Robert Morgenthau launched another investigation into the private carting industry in Westchester. According to the New York Times, the two-year investigation confirmed that carting companies controlled by the Genovese and Gambino families handled 90 percent of the county's commercial waste disposal. The Morgenthau inquiry resulted in two convictions. Vincent M. Fiorillo, the owner of several Westchester carting companies, was sentenced to a year in prison for falsely denying his involvement in a property rights transaction, and a Queens-based carter, Nicola Melillo, a reputed member of the Gambino family, was sentenced to ten years in prison for perjury and extortion.[17]

While the domination of the county's waste hauling business by organized crime figures was well established, it remained for the 1986 inquiry by the New York State Commission of Investigation (SIC) to focus on the extent to which organized crime had managed to corrupt the operations of Yonkers city government.

At that time, Yonkers disposed of its solid wastes through city-owned incinerator facilities. To quote from the SIC's report:

The incinerator facilities of Yonkers are used by private carters as well as city trucks. Private carters who dump at the city incinerator are required to obtain municipal permits and are supposed to bring to the incinerator only waste collected within city limits. These private carters consist of 10 or 11 companies, of which 6 are industrial firms which merely dispose of their own waste. The remaining 5 firms are private carters who collect waste, garbage, and trash from business firms, retail stores and the like. The major private carters are Westchester Carting Corp. and Fleetwood Haulage Corp....

The fee (for the privilege of disposing their garbage) in effect from 1951 to 1965 was $2 up to 2 tons of garbage and 50 cents for each additional ton. .. . In 1965 a new schedule of fees was imposed after a study revealed that the cost to the city for incinerating garbage from private carters was substantially higher than the revenue received. The committee studying the problem was the Budget Committee whose chairman was Councilman Nicholas Benyo. . . . Word began to reach Benyo that he was treading on dangerous ground and that "maybe it would be safer for me if I just didn't do anything on this project."...

Benyo was awakened by a telephone call sometime after midnight (one snowy winter evening). The caller was Councilman James Downes who told Benyo some people wanted to talk to him.

Q. And did he tell you who the people were?

A. Well, he said it was Nick Rattenni, that he wanted to talk to me of this fee--proposed incinerator fee.

Q. Councilman Downes called you at home after midnight and told you that Nick Rattenni wanted to speak to you about the fee?

A. Yes sir.

Q. You mean he wanted you to get out of bed and come down and meet Rattenni?

A. Yes sir.

Q. Where did he want you to have this meeting?

A. At Bruno's Restaurant on Central Avenue.

Q. What did you tell him?

A. When I came there?

Q. No, before you went, on the telephone.

A. Well, I told him that I--you know, this was not an appropriate time, at 12:00 o'clock midnight or so, getting me out of bed, but he suggested that I do go and listen to them, what they have to say.

Q. Can you tell us why you went?

A. Well, I came to two conclusions quickly. If the people, the people who seemed to have problems with me, specifically Rattenni- -if Rattenni wanted to talk to me, and if he was the person that you read about in the papers, then I concluded that if they want to see me, and if I don't go, they are going to find me anyway, so I felt it would be best if I faced up to the situation and get it over with.

Q. Did your wife know you were going?

A. Yes sir.

Q. How did she react to this idea?

A. Well, naturally, she didn't want me to go, and but I went anyway. I told her that if I'm not back by a certain time to call the Second Precinct, to tell them where I went.[18]

Benyo, fearing for his personal safety, went out for the meeting where he met Rattenni, who made it clear that he was unhappy with the increased fees.

Despite the pressure exerted by Rattenni, a new rate structure was enacted that was intended to correct the financial loss to the city of almost $125,000 a year. The victory for Benyo was only illusory, however, as the ordinance that was enacted was not even consistent with his committee's report or recommendations. The new fee schedule was $2 from 0 to 2,000 pounds; $3 from 2,001 to 4,000 pounds; and so on. The fee for 10,001 to 12,000 pounds (five to six tons) would be $5. Benyo's committee had intended that a hauler dropping six tons would have to pay six times $5 or $30, but the way the ordinance was implemented, the hauler dumping the six tons did not pay $5 per ton but $5 for the entire load.[19]

The actual net effect of this unusual interpretation was to raise the dumping fees by only $1 per load dumped. The largest private carters, Westchester Carting and Fleetwood, dumped an average of between 4 to 7 tons a load. Thus for each 4-ton load, the new rates meant a mere increase of 25 cents per ton, while for a 7-ton load, the increase dwindled proportionately to only 15 cents per ton. Since the larger the load, the less it cost per ton, a definite advantage resulted to the larger carting companies, because they had large trucks which could handle the greater loads.[20]

For almost eight years the city had been laboring in vain to solve its garbage problem. An attempt was made in 1966 to find a way out by enlarging the city incinerator. When bids were requested, it soon became evident that this was going to be just another opportunity for corruption.[21] The New York State Commission of Investigation found evidence suggesting that organized crime figures and members of the city council were conspiring together on a shakedown of prospective contractors.

The city should have placed limitations, of course, on the amount of waste that was dumped at the city incinerator by private carters. The city had its own garbage to dispose of, the household garbage collected by city garbage trucks as a municipal service. Some of the municipal garbage was being disposed of at the incinerator, but the city was also carting large quantities of it to the Croton dump, 23 miles away, due to the growing overload of garbage being brought by the private haulers. City Manager Adler attempted in 1966 to limit the amount of garbage that private haulers could bring to the incinerator,

but his efforts were sabotaged by Commissioner of Public Works Maffei, under whose direction the city incinerator was operated. Just as often as the superintendent of the incinerator would turn the private carters away if they had exceeded their quotas, Maffei would call the superintendent and order him to let them in. Although there was a brief interval during which the situation improved, it soon deteriorated to a point where the city could no longer cope with the huge excesses that were accumulating. The city's own garbage trucks could not handle the overload that had to be carted to Croton and the city began turning even more to private contractors.[22]

The city thus found itself in the absurd position of having to pay $8 to $10 per ton to private carters to transport its garbage to Croton, while Rattenni and the other private carters were paying only $1 per ton to use the city incinerator. In addition, the SIC reported that more than half the payments made by the city to private carters went to Rattenni-owned companies, including the newly formed A-I Compaction Corporation, owned by Nick Jr. Rattenni. Other companies, such as ANR Leasing Corporation and Trumid Construction Company, Inc., which participated in hauling to Croton, also showed strong evidence of the elder Rattenni's involvement.[23] (John Masiello, identified as a soldier in the Genovese-Tieri crime family, was a principal in ANR.[24])

Councilman Frank A. Adamo, first elected in 1963 and then reelected in 1965, 1967 and 1969, was also a high school teacher in the Yonkers school system and a friend of Nicholas Rattenni. Two former city managers, the secretary of the Yonkers Board of Contract and Supply (BOCS), the Corporation Counsel and the Deputy Commissioner of Public Works all testified before the SIC to Adamo's intervention in the awarding of contracts on behalf of personal or political friends; and Adamo himself conceded that he had participated in numerous such activities forbidden by the city charter.[25]

Adamo testified that he had first met Rattenni at a social function during his second term in the council and that he was aware of his background and reputation. Nevertheless, he admitted to visiting Rattenni at his home to discuss the operation of the city incinerator.[26]

"This was strange," notes the SIC report, "since Rattenni had nothing to do with the operation of the incinerator."[27] At least, not officially.

On another occasion Adamo invited City Manager Adler to meet him in an out-of- the-way bar in Harrison, New York. When they sat down, Adler testified, Nicholas Rattenni, who was at the bar, came over and joined them. Adler was asked what had happened:

A. We sat down, we ordered lunch, and during the conversation at lunch, Mr. Adamo had in previous conversations, and before the committee meetings in the Council, had made recommendations that he thought the best thing for the City of Yonkers, so far as garbage, would be to have all the garbage collection turned over to private carters.

And the tenor of the conversation at that lunch was that I should cooperate with Frank Adamo to make reports to the Council to show that the City of Yonkers was incapable of handling the garbage problem and to make recommendations to the Common Council to ultimately go to private carting for the collection and disposal of garbage.[28]

This testimony was essentially verified by the SIC report that "Adamo himself made numerous admissions concerning his injection into the area of contract awards."[29] Meanwhile, Ratterini had made sure that the city was incapable of handling garbage collection. Not only had he succeeded in obtaining unlimited access to the city incinerator,but trucking firms controlled by him were making an additional half a million dollars a year transporting household garbage to Croton, which the city was unable to leave at its own incinerator because Rattenni's hauling companies were bringing increased amounts of commercial garbage there.[30]

Rattenni's corrupting influence was not confined to the City of Yonkers. The Republican administration of the Town of Greenburgh awarded the town's garbage hauling contract to A-1 Compaction (Nick Jr.'s company) two years in a row although it was not the initial low bidder. It was later determined that the town was paying A-1 $1,000 per week more than it would have cost the town to do the carting itself.[31]

Now, nearly 20 years later, 35 municipalities in Westchester County are paying for the consequences of Rattenni's racketeering activities, having failed to perceive the warning that the Yonkers situation signaled. As a result, the same drama of exploitation seems to be unfolding again, this time for all of Westchester County, with the same predictability. Only this time it involves 35 municipalities in the county, all of which use the newly opened Signal Resco incineration plant.[32]

Almost immediately after opening in 1984 the Signal Resco plant presented a dilemma to the county. It was built to accommodate contracts with 34 municipalities for an estimated 420,000 tons of waste a year, and has a permit to handle a 657,000-ton capacity. However, some 800,000 tons of waste a year are now in need of disposal. The excess was being carted to the same Croton landfill that Yonkers was using 20 years ago. The excess came about largely because the private carters also used Resco, although they did not at first want to participate. Once the plant was opened, however, they changed their minds.[33] It is also likely that these private carters are bringing in waste to Resco from outside the county and even from outside the state, thereby causing the overload.

A crisis situation had been created because the Croton site was scheduled to close by June 30, 1986. The county would have been justified in telling the private carters that they could not use Resco, but the county had allowed itself to become so dependent on the private carters that if they walked away from their accounts, they would leave the county with a highly embarrassing and also dangerous public health problem.[34]

Westchester County Executive Andrew O'Rourke made two highly controversial and questionable proposals: the first, to purchase the DeMarco-owned Al Turi landfill in Goshen at a cost estimated between $20 million and $50 million,[35] not only to accommodate the excess waste, but also to meet a contractual agreement with Signal Resco, an agreement that was well known to the county for the past several years. The purchase would have involved 300 acres, one-third of which would have included the presently active landfill along with the old Al Turi site, which is on the State's hazardous waste site inventory.[36] This would have made the purchase a risky investment for the county, as it would have to share in the liability in the event that the contaminated section should require extensive cleanup in the future. And the remaining two-thirds would naturally have had to undergo the arduous, time-consuming and expensive permitting process now required by law for all new landfills.

Furthermore, the O'Rourke proposal contained an almost inexplicable irony: in order to accommodate the dumping needs of the private carters - some with mob connections - the county executive would purchase a landfill now owned and operated by

some of those same carters. This proposal would not have benefitted the carters more if they had made it themselves.

The second controversial issue involved a proposal the county executive submitted to the county legislature when Signal Resco opened in 1984. This would have allowed the newly incorporated Intercounty Solid Waste Cooperative to enjoy the same rates as were given to solid waste hauled by or for the municipalities. This would have been at $17 per ton, whether to Signal Resco or to one of the transfer stations. The original rate that had been set for private haulers was $36 a ton to Signal Resco and $65 to the transfer stations.[37]

This O'Rourke proposal would have benefitted the same carters with mob connections by millions of dollars.

The county legislature turned County Executive O'Rourke down and he pulled back his proposal. The Cooperative, which is commonly referred to as "the cartel,"[38] is made up of some 26 carting firms, the biggest of which are Suburban Carting and A-1 Compaction - the former owned by DeMarco in partnership with Thomas Milo, and the latter owned by Nick Jr. Rattenni. Several of the other companies in the cartel are also owned by DeMarco, Milo or Rattenni.[39]

It is noted that Suburban Carting submitted the only bid for hauling waste from nearly all county buildings, although A-1 Compaction is reported to handle the rest of this business.[40]

It is also worth noting that ISA of New Jersey, a Louis Mongeili enterprise, handles the hauling of waste from the Westchester transfer stations to Signal Resco at $26 per ton. How substantial a contract this is can be seen from the fact that about 1,000 tons a day are hauled to Signal Resco from the transfer stations.[41] Louis Mongelli comes under discussion in Sections Two and Seven. Informant reports tie him to Mario Gigante and Thomas Milo, both reputed to belong to the Genovese-Tieri crime family.[42]

After the 1984 proposal was turned down by the county legislature, the cartel continued to use Signal Resco, submitting checks to cover the rate in the rejected proposal rather than the actual rate.[43]

In March of 1985 County Executive O'Rourke returned with a final contract to the county legislature, which would give the cartel a rate of $17.92 for hauling to Resco and $21.92 for hauling to the transfer stations. This was agreed to by the county legislature on a straight, party-line vote.[44]

However, those carters who do not belong to the cartel do not benefit and must pay the standard $36 for hauling to Resco and $65 for hauling to the transfer stations.[45] Moreover, the county executive forgave the cartel the amounts owed for business conducted prior to the approval and accepted their original checks for the lesser amounts.[46]

The deal made with the cartel has already cost the Westchester taxpayers an estimated more than $8 million.[47] Interestingly, the agreement was not formally signed, as the county executive officer was asked not to do so by the attorney general because the deal was under investigation for possible violation of the antitrust law.[48] The county executive, by accommodating the cartel, was creating the same situation that Yonkers had created for itself back in the 1960s and which was spelled out clearly in an SIC report at that time. Westchester County has been paying the private carters the prices they are

demanding and is participating with them in a compact in possible violation of State and federal antitrust laws.

On June 9, 1986, the attorney general's office reminded Calvin E. Weber, Westchester Deputy Commissioner of Solid Waste Management, that almost a year had passed without the county resolving the questions that had been raised with regard to the agreement between the county and the cartel, or "CO-OP." The letter stated, in part:

The agreement between the County and the CO-OP was approved by the Westchester County Board of Legislators on April 15, 1985. It is my understanding, however, that because of our concerns, the agreement has not been fully executed. However, the County is working with the CO-OP as though the contract were in effect. The anti-competitive aspects of the arrangement include the following: (1) private carters belonging to the CO-OP are entitled to dump commercial solid waste at the Charles Point Facility (and related transfer stations) at subsidized tipping fees unavailable to private carters outside the CO-OP; (2) private carters seeking to join the CO-OP may be excluded if all available capacity at the Charles Point Facility has been allocated to CO-OP members; and (3) the CO-OP allocates the limited capacity at the Charles Point Facility among its members. These concerns are underscored by the fact that when the Croton Point landfill closes on June 30, 1986, capacity at the Charles Point Facility will be insufficient to accommodate the solid waste generated in the County and there is no economically feasible alternative dump site. Under the County's arrangement with the carters, when demand exceeds capacity at the Charles Point Facility, CO-OP waste has priority access over non CO-OP private carter waste. As of July 1, 1986, non CO-OP private carters will be excluded from the Charles Point Facility and will be unable to remain effective competitors in the solid waste removal industry in Westchester County.[49]

Quoting another section:

The anticompetitive effects of the County's arrangement with the CO-OP are already being felt in the Westchester carting industry. As I am sure you are aware, CO-OP carters pay a tipping fee of $17.92 per ton and $21.92 per ton at the Charles Point Facility and transfer stations, respectively. Carters outside the CO-OP pay $36.00 and $65.00, respectively. At least one private carter has been forced out of business due to his lack of CO-OP membership. Another carter has complained about his inability to joint the CO-OP and the difficulty he faces in competing with CO-OP carters whose costs are so much lower. Furthermore, by charging below market rates to CO-OP members, the County has lost substantial revenue.[50]

The letter then reviews the numerous attempts the attorney general's office had made to encourage the county to withdraw from the agreement. The letter concludes:

The best solution as a matter of antitrust law and public policy is for the County to immediately abandon the agreement with the CO-OP and to impose market value tipping fees on all private carters at the Charles Point Facility and Transfer stations. However, I must advise you that if this matter is not fully resolved in the very near future, this

office will have no choice but to commence litigation, pursuant to the Donnelly Act, the Sherman Act, or both, against the County and the CO-OP.[51]

Committee staff, in its investigations, learned of O'Rourke's proposal to buy the Al Turi landfill, and Chairman Hinchey commented to the press in April 1986 regarding the inappropriateness of the planned purchase;[52] and on May 31 he spoke in more detail on the matter, as well as on the antitrust nature of the arrangement with the cartel.[53]

Westchester County Executive O'Rourke almost simultaneously announced that he was breaking off negotiations for the AL Turi landfill,[53a] and on June 3 he wrote Chairman Hinchey claiming no prior knowledge that illegal dumping in the past had taken place at the site and suggesting that the committee, DEC and the attorney general had been remiss in not notifying Westchester of the problems that existed.[54]

Chairman Hinchey replied on June 12:

In response to your letter of June 3, 1 must advise you that the information regarding Al Turi landfill and organized crime's involvement in the Westchester carting industry has been a matter of public knowledge for several years. It would seem that there has been a failure of communication between you and Westchester County District Attorney Carl Vergari, who has long been acquainted with the kind of material which this committee has been investigating. In the Sunday New York Times of October 13, 1974, it was reported that Mr. Vergari was launching an investigation into possible bribery and extortion in the carting industry. In the article he is quoted as having referred to A-1 Compaction owned by "Nick Jr." Rattenni as dominating carting in Yonkers and southwest Westchester. The same article also refers to Suburban Carting, which is owned by Thomas Milo and Alfred DeMarco, and notes that Milo's uncle had been linked by federal authorities with the Genovese crime family. The Milo and Rattenni names have long been familiar to those who read Westchester newspapers. DeMarco, of course, is the owner of Al Turi landfill which you were going to purchase a few weeks ago.

Your pulling back from the deal apparently indicates that you recognize the dangers that would be involved in the purchase of this landfill. Of even greater concern, however, should be the arrangement you have worked out with the cartel known as the Intercounty Solid Waste Cooperative, which is described on pages 49 through 51 of the forthcoming report. (I am enclosing the draft section in which these pages occur so that you will have adequate opportunity to appreciate our concerns and offer your explanations.)

If you have not already done so, I would suggest that you respond immediately to the letter sent to your Commissioner of Solid Waste Management by the New York State Attorney General's office, dated June 9, 1986. The deal you have worked out with the cartel is strikingly reminiscent of the situation the Westchester City of Yonkers created for itself back in the Sixties; and which will be found in the enclosed material. It was also spelled out clearly in the State Commission of Investigation's report at that time. The consequences of your arrangement with the cartel are that Westchester is paying the private carters

prices they are demanding for problems which they themselves created. And dominating the cartel are the same Nick Jr. Rattenni and Thomas Milo mentioned above.... This Committee would certainly be interested in a further explanation from you of the peculiar informal agreement you have reached with the cartel.

I note that the Attorney General's Office comments to this effect on your uncooperative behavior:

"Since last August Ms. Gross has had numerous contacts with Kaye, Scholer in a further attempt to persuade the County to abandon the CO-OP arrangement. This office has afforded the County every opportunity to avoid a lawsuit. The County has not taken advantage of these opportunities and has reneged on many of the promises it has made."

I must take exception to your complaint that Westchester has had to search for landfill sites in order to comply with DEC landfill regulations. I hope you realize that those regulations were instituted to protect the health and safety of the citizens of this State. If the DEC is to be faulted at all, it is for leaning over backwards to give municipalities every opportunity to make an orderly transition to proper waste management practices.

Similarly, your suggestion that the Assembly Environmental Conservation Committe and the State bureaucracy may be lax in conveying to you the facts about, the Al Turi landfill, ignores the numerous accounts that have appeared in the press over the past decade. Moreover, the original site had been placed on the State's Inactive Hazardous Waste Site Registry in 1983 and is required to be on file with the Westchester County Clerk. Moreover, it is our understanding Mr. Weber had informed you of this.

It would have been helpful if Mr. Vergari had explained to you why one cannot, under present law, close down a landfill simply because people with reputed organized crime backgrounds are associated with it. But although the law does not permit automatic closure of such landfills, it certainly is not prudent to become involved in negotiations with such individuals and make expensive purchases from them, especially when those purchases involve public funds. Your cooperation. with them in anticompetitive practices appears to be even more serious.

Finally, you have charged that the attacks on you are politically motivated. Certainly, they are - in the best sense of the word. It would be abdicating my responsibility as chairman of the committee investigating such questionable practices if I did not call them to the attention of the public when you are seeking election to the highest office in the State.

As soon as the complete report on organized crime's involvement in the carting industry is available, I will be pleased to send you a copy, so that you can see that it focuses on just the kind of activities which are currently taking place in Westchester.[55]

Mr. O'Rourke called a press conference the same day--this time to announce that he was going to abandon the agreement he had worked out with the cartel.

Additional details that have been learned through staff inquiries:

The wife of DeMarco's lawyer, Diane Keane, a Republican-Conservative member of the Westchester County Legislature, also sits on the budget committee and vice chairs the county board. Furthermore, she sometimes sits in for the chairman of the county board, who has a seat on the Board of Acquisition and Contracts. This has caused some speculation.

Moreover, Mrs. Keane could possibly be involved in a conflict-of-interest situation, as she did not remove herself when a decision had to be made and she voted in favor of the contract with the Cooperative when the issue came before the county legislature in March of 1985.[56]

The Board of Acquisitions and Contracts approved a $20,000 appraisal fee for the DeMarco landfill in April of this year. It also approved the option-to-purchase agreement for the landfill, which required that if the county wished to extend the option beyond the initial 45-day limit it would pay DeMarco $20,000 each month for an additional five months, with the provision that this sum would be deducted from the purchase price if the county decided to buy. In other words, if the option had been picked up, DeMarco was to receive $100,000, even if the property was not bought by the county.[57]

Another aspect of the situation that has prompted speculation is that one of the conduits for the channeling of campaign funds to Republican candidates in Westchester, the Builders Institute of Westchester and Putnam Counties, headed by George Frank, has the same business address as the Intercounty Solid Waste Cooperative.[58] Also, the cartel can be reached by calling the Builders Institute telephone number.[59]

Conversations with Westchester officials confirm that bid-rigging, price-fixing and gouging are rampant. Frank Bohlander, Commissioner of Public Works, told our staff researcher that he did not consider this something for his office to be dealing with, but that it was a law enforcement problem. That it was a problem he readiy conceded, saying, "they are gouging the hell out of us."[60]

On June 13, 1986, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, on learning of the disclosures about Al Turi Landfill, Inc., put a hold on an agreement it had entered into with DeMarco regarding development of an advanced liquid-treatment system for industrial wastes and energy conservation.[61]

Staff Notes

The elder Rattenni, with a criminal record and established organized crime connections, became powerful in the Westchester carting industry in 1949, when the Yonkers Common Council turned over commercial and industrial garbage collection to private carters.

Police records and investigations of his activities going back at least as far as 1957 indicate that his operations involved:

1. Organized crime connections;

2. Control of the union of carting workers;

3. Use of force, intimidation and murder of rivals;

4. Improper and coercive influence on local officials;

5. Use of bid-rigging and the property rights system to jack up carting fees.

The elder Rattenni's operations provide a graphic example of organized crime's ability to corrupt the governmental process. This corrupting influence will be evident in other sections of this report, particularly in those dealing with New York City, Long Island and such giants in the industry as SCA and BFI. While it would be naive to assume that some legitimate businesses do not also employ some of the same methods of bribery, threats of retaliation, coercion through monopoly control, old-boy networks and plain conspiracy - organized crime's special contribution has been the threat and actual use of physical violence in order to extend its marketing operations and the interweaving of legitimate business enterprises with their other, purely criminal activities.

It is impossible to say to what extent the elder Rattenni was in full control of the solid waste hauling empire he had built up in Westchester during his lifetime and to what areas it extended outside New York State. It was apparent as far back as 1957 that he had achieved some eminence in the hierarchy of organized crime. His operations later spread beyond Westchester into Connecticut and other counties in the Mid-Hudson Valley.

The current problems facing Westchester County could have been avoided if public officials had heeded the lessons that the Yonkers situation could have taught.