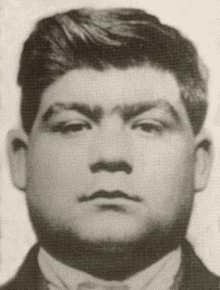

Joe Tocco

Giuseppe “Joe” Tocco parked his trademark scarlet sedan on Wyandotte’s Antoine Street near the intersection with McKinley. It was about half past nine, Monday night, May 2, 1938. His residence was around the block at 238 Felice Street, but the Detroit-area rackets chief wasn’t headed home yet. He walked a short way down the street toward the home of his close associate James Palazzolo when firearms erupted from the darkness.

Tocco bolted, slipping between houses and making his way to the rear porch of the Palazzolo home. At least two gunmen followed. As he climbed stairs to the porch door, 215 Antoine, more shots were fired. Slugs cracked through glass in the door and a nearby window. Inside, the hand of Rose Palazzolo, wife of James, was cut by flying glass. Tocco stumbled through the doorway with seven wounds in his back. James Palazzolo was not home. Tony Bozzo of 245 Antoine Street was summoned, and he drove Tocco to Wyandotte General Hospital.

Doctors tended to Tocco’s wounds, determining that they were inflicted by shotgun and pistol fire. Detectives explored the shooting scene and took statements from witnesses. Assistant Prosecutor Harry B. Letzer was called to the hospital and questioned Tocco. The forty-seven-year-old mafioso with a lengthy police record, including eleven arrests dating back to 1915, initially refused to make any statement. Later, he did provide some information about the incident, describing his movements as he attempted to elude his assailants. He said he did not see the gunmen’s faces and had no idea who they were. [1]

On Tuesday morning, doctors transfused blood from Tocco’s brother Peter into their rapidly fading patient. At four o’clock that afternoon, Tocco succumbed to his wounds. An autopsy revealed the primary causes of death were internal hemorrhage resulting from a wound to his kidney and hemorrhage into the spinal cord. Tocco was survived by his wife Agata Consiglio Tocco, four grown children and a four-year-old son.

After a funeral Mass at St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church, then located at First and Goodell streets, Tocco was interred at Mount Carmel Cemetery on Ford Avenue between Seventh and Ninth streets. A press report indicated that he was buried within a gray mother-of-pearl coffin, lined with cream-colored satin and valued at $1,050 (about $22,800 in current dollars). [2]

Joe Tocco was born December 19, 1890, in Terrasini, a coastal community in Sicily’s Palermo province. His parents were Salvatore and Rosalina Moceri Tocco. He was only about fifteen when he sailed to America and settled with relatives in the Detroit area. The Downriver village of Ford City (founded a few years earlier by chemical company owner John Baptiste Ford and absorbed into the city of Wyandotte in 1922) soon became home to Joe Tocco and his brother Pietro. Tocco appears to have entered the local rackets with the Ford City-based Giannola gang. [3]

Another Tocco from the Terrasini area – Guglielmo or William (often referred to as “Black Bill”) – settled in the city of Detroit in the 1910s. William’s family was tightly linked with the Zerilli clan, and both became powerful in a Mafia organization based Detroit’s East Side. Though William’s surname, his native Sicilian community and his mother’s maiden name (Moceri) were all matches for Joe Tocco, he insisted that he and Joe were no relation. Joe Tocco and William Tocco were often rivals in the factionalized Sicilian underworld of Southeast Michigan. [4]

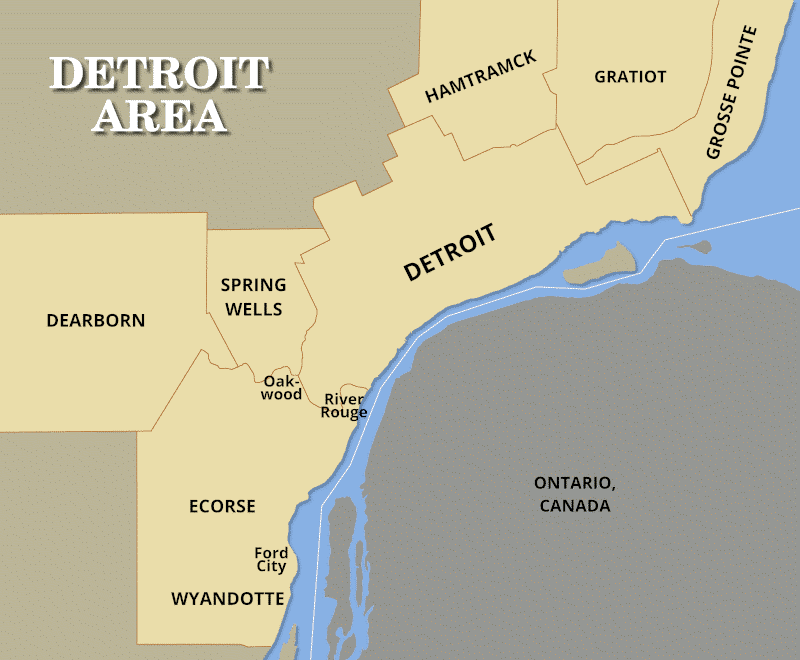

Detroit region circa 1915.

In early July 1912, Joseph Tocco married Agata Consiglio, seventeen, in a Roman Catholic ceremony in Wyandotte. Son Salvatore was born to the couple in late 1914, and daughter Rosalia followed in early 1916. [5]

At the time of his mid-1917 World War I draft registration, twenty-six-year-old Tocco reported that he was living at 40 Antoine Street in Ford City and working as a packer at the Michigan Alkali Company. He was described as medium height, with a slender build, blue eyes and red hair. He claimed an exemption from military service based on his dependent wife and children. Tocco’s brother Pietro, twenty four, noted the same home address and employer on his own registration. Pietro was described as medium height, stout, with brown eyes and brown hair. [6]

As 1918 opened, son Vincenzo was born to Joe and Agata Tocco. Twin daughters, Eva and Phyllis arrived in October of the following year. [7]

While the Great War drew to a close in Europe, a bloody conflict erupted in the Detroit region. The Downriver gang led by the Giannola brothers, originally from Terrasini (also born to a mother whose maiden name was Moceri), was torn apart following Giannola disagreements with former partners Peter Bosco, native of Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily, and John Vitale, originally from Cinisi.

Sam Giannola

The ensuing Giannola-Vitale War resulted in the deaths of many rackets figures, including brothers Tony and Sam Giannola, their brother-in-law Pasquale D’Anna, Peter Bosco, John Vitale and Vitale’s son Joseph. It also helped Joe Tocco rise through the underworld ranks, though the rewards for advancement had yet to be realized. [8]

The Prohibition Era opened with Joe Tocco and his family apparently in financial difficulty. The U.S. Census compiled in January 1920 found the family living in a rented portion of the Consiglio home, 37 Phyllis Street. Tocco reported working as a carpenter. Just two days after being noted on the census, daughter Phyllis died. She was just three months old. The cause of death was listed as inanition, with “improper feeding” noted as a contributory cause. [9]

Tocco fortunes changed with entry into bootlegging rackets. He began a profitable partnership with Cesare “Chester” LaMare, an immigrant from the southern Italian mainland who ran produce companies and cafes in Hamtramck. [10] Over time, Tocco became known as “the beer baron of Wyandotte,” though his underworld influence stretched beyond the community’s boundaries.

Tocco’s daughters Agatha and Josephine were born in 1921 and 1923. Tocco declared his intention to become a U.S. citizen in 1926. At that time, he was a resident of 42 Felice Street. His citizenship was approved by summer of 1928, after he had moved his family into a spacious new home – described by one newspaper as a "pretentious twenty-room mansion" – at 238 Felice. [11]

Early in 1929, Tocco took daughter Rosalia and son Vincenzo on a trip to his native Italy. They returned aboard the steamer Roma, arriving in New York harbor in March. About six months later, the family suffered a tragic loss. Tocco’s youngest child, six-year-old Josephine, was crushed to death by an automobile on August 30. [12]

In the later Prohibition period, LaMare and Tocco became influential within the Detroit area facilities of Dearborn-based Ford Motor Company. Noting sporadic violence and persistent unionizing efforts among Sicilian workers, Ford officials formed a relationship with the mobsters in the interest of maintaining order. But the relationship went beyond that. Harry Herbert Bennett, who handled much of Henry Ford Sr.'s dirty work between about 1921 and 1945, is believed to have employed mobsters within Ford facilities to set up union organizers for arrest/dismissal and to violently crack down on labor demonstrations. [13]

Tocco became a frequent visitor to company management. He and other underworld figures used the new influence to insert underlings and allies into roles in the Ford company and to work out lucrative concession and agency deals with Ford. LaMare and Tocco recognized that their wealth and status had become tied to their exclusive access to Ford executives, and they jealously protected their position. [14]

Bennett

For the 1930 U.S. Census, the value of the Tocco home at 238 Felice Street was estimated at $18,000.($325,000 in current dollars). A close friend and business associate “Black Ben” Sciacca lived nearby at 256 Felice, in a home valued at half that amount. [15]

The LaMare-Tocco combination was assembling racket monopolies, beginning to control the local manufacture of alcoholic beverages, the regional flow of beer and liquor, and the hiring and firing at Ford. That caused friction with other elements of the regional underworld, particularly the East Side organization.

LaMare decided in spring 1930 to resolve the differences. With secret approval from New York-based Mafia boss of bosses Giuseppe Masseria, LaMare set up an ambush for other underworld leaders at a May 31, 1930, meeting he billed as a peace conference. The Mafia bosses of the East Side wisely chose not to attend. Gaspare Milazzo, a leading figure among the Castellammare del Golfo mafiosi in the U.S., and his aide Sam Parrino showed up for the meeting at a fish market on East Vernor Highway. Both men were fatally shot. [16]

LaMare

His duplicity exposed, and his most feared enemies unharmed and angered, LaMare fled the area and went into hiding for months. While he was away, his close ally and business partner Joe Marino was fatally shot. Marino went to answer the door of his Dearborn home on Saturday, September 27, 1930. As the door opened, he was shot in the chest. An investigation resulted in two conflicting confessions - one, later retracted, by Marino's own son - and insistence by the dying victim and all witnesses that the shooting was entirely accidental.

When LaMare returned to Detroit early in 1931, he was assassinated – shot in the head probably by someone he trusted. Police picked up and questioned and ultimately released Joseph Zerilli and William Tocco of the East Side Mafia. [17]

An important LaMare lieutenant, Tony Marino (uncertain if there was any relationship to Joe Marino), was hospitalized with a fractured skull at about the same time LaMare was murdered. Marino said he suffered it in a bar brawl. Police initially considered him a suspect in the LaMare murder, feeling that his skull injury was a match for a broken chair found near LaMare's body, but Marino's alibi checked out. [18]

There were rumors that Joe Tocco, too, was targeted for assassination in the early 1930s.

A couple of decades later, Kefauver Committee Associate Counsel John L. Burling made those rumors public. He suggested that Harry Herbert Bennett, powerful Ford executive and close ally of Tocco, learned of the plot and summoned racketeer Anthony D’Anna to his office. Anthony D’Anna was the son of the Pasquale D’Anna murdered in the Giannola-Vitale War, and he and was reportedly struggling against Tocco in Wyandotte.

While questioning witnesses in a February 1951 hearing, Burling revealed his belief that Bennett offered Anthony D’Anna a share in a highly profitable Ford agency in Wyandotte in exchange for calling off the hit on Tocco. Both Bennett and D’Anna denied that any such deal was made or discussed, though both acknowledged that D’Anna, with limited financial resources and no experience in the automobile business, did acquire a share in the agency at that time. [19]

Ulike his rackets colleagues Cesare LaMare and Joe Marino, Tocco avoided assassination in the early 1930s, but those were still troubling years for him.

Authorities believed he had some role in what became known as the Wyandotte Massacre. A little after eight o’clock on Friday night, November 6, 1931, three gunmen burst into a speakeasy run by Charles Tear at 3331 Biddle Avenue and let loose with a hail of slugs from two pistols and a shotgun. Tear, Joe Rivetts and bartender John Pellitier were killed. The gunmen were gone in about a minute, escaping in a brown sedan driven by a fourth man. [20]

Police knew that Rivetts, formerly operator of his own speakeasy, had serious trouble with an Italian bootlegging gang in the area. Two weeks earlier, after Rivetts refused to buy beer from the organization, gangster Joe Evola went by Rivetts’s place, Oak Avenue and First Street, to kill him. Rivetts was quicker on the draw and fatally shot Evola. Officially, Rivetts’s action was justified as an act of self-defense. Police assumed that gangsters saw things differently and wanted to settle the score with Rivetts and his allies. [21]

Joe Tocco and a number of associates, friends and relatives were arrested, questioned and held for a time after the massacre. Authorities raided and destroyed Tocco breweries in Wyandotte, including two near his Felice Street home. A special inquiry was conducted into the triple-murder. Ultimately, Tocco was able to back up an alibi for November 6, and he was released. [22]

In December, federal agencies seemed to target Tocco. Officials of the Bureau of Internal Revenue announced that they were examining his tax returns. (Less than two months earlier, Chicago crime boss Al Capone had been convicted of income tax evasion and sentenced to a lengthy prison term.) At the same time, the Bureau of Immigration began an effort to deport both Tocco and “Black Benny” Sciacca. Neither of these federal efforts was productive. [23]

Ruins of Tocco residence. (New York Daily News)

Tocco’s extravagant home exploded in flames at about nine o’clock Sunday night, February 21, 1932. Witnesses heard several minor explosions followed by a succession of three loud blasts, as the fire erupted. Tocco was traveling at that time (Ben Sciacca showed authorities a postcard Tocco recently sent him from Miami, Oklahoma), and Agata and the children were off in Detroit. No one was hurt. Investigators suspected arson. An arson expert from Detroit and an assistant prosecutor were called in to examine the matter. But it was apparently quietly resolved before Tocco returned to Wyandotte. [24]

Tocco almost immediately set to work rebuilding the home in brick and stone. [25]

The Michigan State Liquor Control Commission heard in 1935 that Joe Tocco and some other Detroit-area crime figures, including East Side Mafia leaders Joseph Zerilli and William Tocco, controlled distribution for a local beer company. The commission received a complaint that the group was forcing retailers to accept that brand of beer. Turning the matter over to the state attorney general, the commission announced that no person with a criminal record would be granted liquor licenses. Joe Tocco and the other underworld leaders reportedly surrendered their roles with the distributor in order to avoid further legal action. [26]

Joe Tocco seemed to learn that exposure was the enemy of organized crime. He began to handle underworld rackets remotely, using trusted men as his agents, while he remained largely out of the public eye.

Around the middle of the decade, he partnered with Sam Rossi in the operation of the Kitty Kat Beer Garden. That establishment was located at 635 South Bayside Avenue near Greyfriars Street in Detroit’s Oakwood Heights section, just south of the River Rouge and close to Ford's "Rouge" plant.

Rossi’s wife Gina, working as a waitress in the beer garden, apparently caught Tocco’s eye. According to rumors, Tocco convinced Sam Rossi to return to his native Italy and leave the business and his wife (and, apparently, two school-age children) in Tocco’s care. Using his influence in the local automotive industry, Tocco obtained a more profitable and less visible role for Mrs. Rossi, as he began a long-term affair with her. Tocco’s wife and grown sons learned of his relationship with Gina Rossi, and that, according to one news report, “resulted in many family quarrels.”

Tocco spent so much time at Gina Rossi's home, located on the same street as the beer garden, that he had a telephone installed there for his business use. Her household became a regular stop for Tocco-sponsored thugs from Ford. At a National Labor Review Board hearing in 1941, witness William A. Stinson testified about rides to and from work with a gun-toting thug named Dempsey. "When I rode with him we used to stop at the Kitty Kat Klub on Greyfriars where Dempsey met Joe Tocco and his men." Stinson recalled a meeting "in Gene [likely Gina] Rossi's place across from the Kitty Kat." That meeting was a strategy session to prevent labor union "sound cars" from gaining access to the Ford plant. [27]

In the same period, Tocco opened a gambling establishment at 311 South Fordson Street, also in Oakwood Heights. That business was closed near the end of 1937. [28]

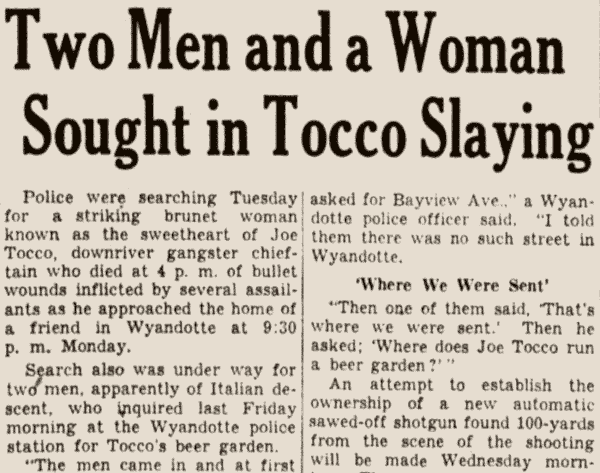

On the Friday before Tocco was murdered, April 29, 1938, two men showed up in Wyandotte looking for him. They went into the local police station asking for directions to “Bayview Avenue.” They were told that there was no such street in Wyandotte. One of the men said, “That’s where we were sent.” The men then tried another question: “Where does Joe Tocco run a beer garden.” They learned that the location was on Bayside Avenue in Oakwood Heights. [29] Whether the men were at all involved in Monday night’s shooting remains unknown.

Detectives investigating the murder of Joe Tocco quickly learned that he had spent the early part of the evening at Gina Rossi’s home and then drove over to Palazzolo’s house, where a meeting with rackets figures was to be held. Palazzolo and Tocco’s brother Peter were occupied with some errands and were slow to show up for the meeting. Mrs. Rossi apparently spoke briefly to a newspaper reporter after the shooting, but when the authorities went looking for her, the thirty-six-year-old woman and her children were gone. Her house was deserted, and she failed to show up for work. Police wondered if Sam Rossi had returned from Italy and reclaimed his family. [30]

Detroit Free Press, May 4, 1938.

A partly loaded repeating shotgun was found discarded in a ditch about one hundred yards from where Tocco was shot. It contained four unfired shells. Detroit police used ballistics testing to determine that the shotgun was one of the murder weapons.They were unable to find any fingerprints on the firearm. [31]

While Joe Tocco’s demise permitted Joseph Zerilli’s East Side Mafia to consolidate its control in the southeastern Michigan underworld, some imagined that other forces had been behind the killing, perhaps Tocco’s own family members.

Harry Herbert Bennett said as much when he discussed the Tocco murder in the February 1951 Kefauver hearings. Associate Counsel Burling directly asked Bennett, “Do you know who did it?” While Bennett’s officially transcribed answer in the hearing minutes appears to have been edited out, a news reporter recorded the exchange:

“No, but the police had a good idea,” Bennett said.

“Who?” Burling asked again.

Bennett replied, “They believe members of his family.”

However, Bennett conceded he knew more about the regional underworld than he was telling. He had made it a point during his years at Ford to keep in touch with bosses of area gangland factions. When first asked if he knew hoodlums like Tocco, Bennett replied, “Oh, sure. Everybody in Detroit knew him…. If you want to call them a hoodlum, there is Joe Tocco and Joe Marino and LaMare – the whole LaMare crowd.” Questioned about the still living leaders of other underworld factions, Bennett refused to answer: “Do you want me to get my head blown off out here?” [32]

1 "Ex-gangster chief shot," Detroit Free Press, May 3, 1938, p. 1; "Two men and a woman sought in Tocco slaying," Detroit Free Press, May 4, 1938, p. 1; "Detroit tavern keeper killed," Escanaba MI Daily Press, May 4, 1938, p. 2; "Joe Tocco, ex-beer baron, dies with lips sealed on identity of slayer," Lansing MI State Journal, May 4, 1938, p. 1; "Tocco's love affairs probed as police question relatives," Detroit Free Press, May 5, 1938, p. 1.

2 Joe Tocco Certificate of Death, State Office No. 882-4519, Register no. 119, Wyandotte City, Wayne County, Michigan Department of Health Bureau of Records and Statistics, May 3, 1938; "Ex-rum chief shot in gang war outbreak," Port Huron MI Times Herald, May 3, 1938, p. 1; The Lady in Black, "Joe Tocco," Memorial ID 71839481, Find A Grave, findagrave.com, June 22, 2011; "Tocco's love affairs probed as police question relatives," Detroit Free Press, May 5, 1938, p. 1.

3 Joe Tocco Certificate of Death, State Office No. 882-4519, Register no. 119, Wyandotte City, Wayne County, Michigan Department of Health Bureau of Records and Statistics, May 3, 1938; Joe Tocco World War I Draft Registration Card, no. 318, Wayne County District 8, Wyandotte City Hall, June 5, 1917; Joseph Tocco Petition for Naturalization, petition no. 34511, filed Aug. 1, 1928, certificate no. 2834890, certificate issued Nov. 26, 1928.

4 Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce - Part 9, Michigan, United States Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951, p. 249.

5 Joseph Tocco and Agata Consiglio, record no. 86614, Michigan Marriages, 1868-1925, FamilySearch.org; Joseph Tucco and Agata Consiglio, Wayne County, Michigan Marriage Records, Ancestry.com; Joseph Tocco Petition for Naturalization, petition no. 34511, filed Aug. 1, 1928, certificate no. 2834890 issued Nov. 26, 1928.

6 Joe Tocco World War I Draft Registration Card, no. 318, Wayne County District 8, Wyandotte City Hall, June 5, 1917; Pietro Tocco World War I Draft Registration Card, no. 32, Wayne County District 8, Wyandotte City Hall, June 5, 1917.

7 Joseph Tocco Petition for Naturalization, petition no. 34511, filed Aug. 1, 1928, certificate no. 2834890 issued Nov. 26, 1928; Phyllis Tocco Transcript of Certificate of Death, registered no. 6, Ford Village, Ecorse Township, Wayne County, State of Michigan Department of State - Division of Vital Statistics, Jan. 24, 1920.

8 "Feudist chief falls to foes; another slain," Detroit Free Press, Sept. 29, 1920, p. 1; Waugh, Daniel, "The assassination of Sam Giannola," Writers of Wrongs, writersofwrongs.com, Oct. 2, 2019; "Massacre veil lifted by witness," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 16, 1931, p. 1; Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce - Part 9, Michigan, United States Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951, p. 11.

9 United States Census of 1920, Michigan, Wayne County, Village of Ford, Enumeration District 676; Phyllis Tocco Transcript of Certificate of Death, registered no. 6, Ford Village, Ecorse Township, Wayne County, State of Michigan Department of State - Division of Vital Statistics, Jan. 24, 1920.

10 Chester W. LaMare World War I Draft Registration Card, Precint 2-1W Detroit, no. 1657, June 2, 1917; United States Census of 1920, Michigan, Wayne County, Detroit, Ward 2, Enumeration District 68.; "Secures protection from illegal arrest," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 5, 1921, p. 3; "Arrest Detroit man following shooting," Battle Creek MI Enquirer, Sept. 7, 1923, p. 1.

11 Joseph Tocco Petition for Naturalization, petition no. 34511, filed Aug. 1, 1928, certificate no. 2834890 issued Nov. 26, 1928; Joseph Tocco Declaration of Intention, no. 55707, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, March 19, 1926; "Blasts wreck Tocco's home," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 22, 1932, p. 1.

12 Passenger manifest of S.S. Roma, departed Naples on Feb. 23, 1929, arrived New York, March 5, 1929; Josephine Tocco Transcript of Certificate of Death, registered no. 208, Wayne County, Michigan, Aug. 30, 1929.

13Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce - Part 9, Michigan, United States Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951, pp. 75-76, 82-83; Wilson, Amy, "The rise and fall of Harry Bennett," Automotive News, June 2, 2003; Pooler, James S., "Ford peace in air at NLRB trial," Detroit Free Press, June 6, 1941, p. 3.

14 Smith, Rowland, "River Rouge: Gangsters and petty politicians have key to jobs at Ford plant," United Automobile Worker, Oct. 8, 1938, p. 10; Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce - Part 9, Michigan, United States Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951, pp. 25, 52.

15 United States Census of 1930, Michigan, Wayne County, City of Wyandotte, Enumeration District 82-1072.

16 Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, pp. 93-94, 100; "Riddled by lead slugs," Detroit Free Press, June 1, 1930, p. 1; "Tip says one of Saturday's victims is wanted for murder," Detroit Free Press, June 2, 1930, p. 3; Gaspari Milazzo death certificate, Michigan Department of Health Division of Vital Statistics, Reg. No. 7571, June 1, 1930.

17 "Gangs receive machine guns," Detroit Free Press, Sept. 18, 1930, p. 1; "Marino dies; story doubted," Detroit Free Press, Sept. 30, 1930, p. 5; "Dearborn man admits killing," Lansing MI State Journal, Oct. 2, 1930, p. 1; "Detroit gang leader killed in own kitchen," Lansing MI State Journal, Feb. 7, 1931, p. 1; Chester Sapio Lamare Death Certificate, Michigan Department of Health Division of Vital Statistics, State office no. 140778, register no. 1599, Feb. 7, 1931; "Mob leader 'put on spot,' belief of investigators," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 8, 1931, p. 1; "LaMare, lord of West Side, assassinated," Escanaba MI Daily Press, Feb. 8, 1931, p. 1; "Two men held for grilling in death of gang chieftain," Benton Harbor MI News-Palladium, Feb. 10, 1931, p. 12.

18 "Gangs feared expose by La Mare, report," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 8, 1931, p. 1; "Graft link in La Mare case seen," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 9, 1931, p. 1.

19 Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce - Part 9, Michigan, United States Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951, pp. 20, 23, 26.

20 "Thugs massacre 3 in Wyandotte saloon," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 7, 1931, p. 1; "Massacre veil lifted by witness," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 16, 1931, p. 1; "Murdered men suspected as German spies," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 17, 1916, p. 1.

21 "Thugs massacre 3 in Wyandotte saloon," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 7, 1931, p. 1; "Wyandotte gang inquisition opens today," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 13, 1931, p. 1.

22 "Wyandotte gang inquisition opens today," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 13, 1931, p. 1; "Tocco 'sick of racket,'" Detroit Free Press, Nov. 20, 1931, p. 3; "Raid nets Sam Tocco," Detroit Free Press, Dec. 2, 1931, p. 8.

23 "U.S. starts Tocco probe," Detroit Free Press, Dec. 4, 1931, p. 5; "Tocco, Sciacca freed on bail," Detroit Free Press, Dec. 11, 1931, p. 8

24 "Blasts wreck Tocco's home," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 22, 1932, p. 1; "Police discover evidence of arson in debris of bootleg king's abode," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 23, 1932, p. 13

25 "238 Felice St, Wyandotte MI," Zillow, zillow.com.

26 "Gang reported in beer trade," Detroit Free Press, Feb. 20, 1935, p. 2; Sclafani, Joe, "Story of Joe Tocco," Ancestry, ancestry.com, July 5, 2013.

27 "Tocco's love affairs probed as police question relatives," Detroit Free Press, May 5, 1938, p. 1; "Two men and a woman sought in Tocco slaying," Detroit Free Press, May 4, 1938, p. 1; "Officers free kin of Tocco," Detroit Free Press, May 6, 1938, p. 2; Pooler, James S., "Ford peace in air at NLRB trial," Detroit Free Press, June 6, 1941, p. 3.

28 "Two men and a woman sought in Tocco slaying," Detroit Free Press, May 4, 1938, p. 1.

29 "Two men and a woman sought in Tocco slaying," Detroit Free Press, May 4, 1938, p. 1.

30 "Tocco's love affairs probed as police question relatives," Detroit Free Press, May 5, 1938, p. 1.

31 "Two men and a woman sought in Tocco slaying," Detroit Free Press, May 4, 1938, p. 1.

32 Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, Investigation of Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce - Part 9, Michigan, United States Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951, p. 84.