Firing bullets into others helped "Cadillac Frank" earn the notice of the New England Mafia. But Francis Patrick Salemme might not have reached the top level of that criminal organization without the bullets that were fired into him.

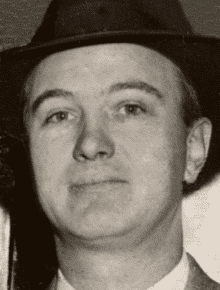

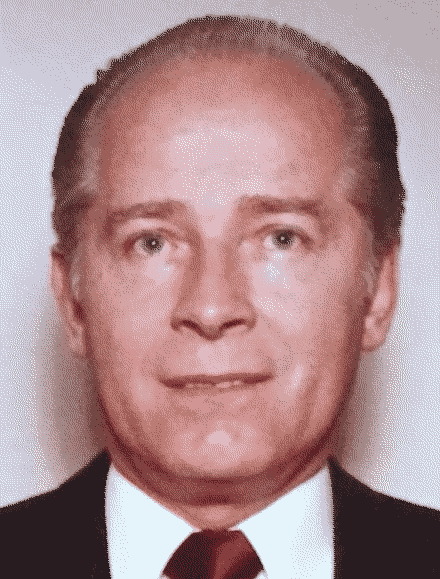

Cadillac Frank

On June 16, 1989, Salemme was walking across an International House of Pancakes parking lot at Saugus, Massachusetts, when a gunman in a slow-moving car opened fire on him. The car made two passes as Salemme scrambled for cover, reaching relative safety inside a Papa Gino's pizza shop. Police found him there with serious gunshot wounds to his chest and leg. As they worked to save his life, Salemme refused to talk. He wouldn't acknowledge seeing the car or the shooter. He wouldn't even identify himself. He was rushed to AtlantiCare Hospital in Lynn, where doctors tended to his wounds for the next nine days.

The shooting incident defied explanation until later on the sixteenth, when the dead body of William P. "Wild Guy" Grasso of New Haven was found along the Connecticut River in Wethersfield, Connecticut. The medical examiner determined that about twenty-four hours before he was found Grasso had been the recipient of a gunshot wound to the base of his skull.

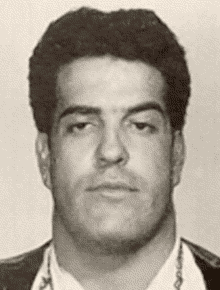

Grasso

Authorities knew that Salemme and Grasso shared a significant distinction. Both were increasingly important members of a New England Mafia faction loyal to boss Raymond J. "Junior" Patriarca. The son of longtime rackets chief Raymond L.S. Patriarca, "Junior" took over after his father's death in 1984 but lacked his father's strength and charisma. A rebellion apparently had started against his rule, and anti-Patriarca forces were determined to eliminate the boss's most powerful backers. (Agents at the FBI already concluded, but did not reveal for quite some time, that the FBI itself had sparked that rebellion through a misguided divide-and-conquer strategy. Agents hoping to turn informants secretly advised crime family members in Massachusetts and Connecticut that Rhode Island-based Patriarca was planning to have them killed.) [1]

Four months after Salemme returned to his residence in Sharon, Massachusetts, the Patriarca administration held an induction ceremony at a home at Medford. Salemme, still recovering from his wounds, was excused from the gathering. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as FBI had planted some excellent listening devices in the building and recorded the ceremony and conversations. [2]

The shootings in June and the bugged ceremony in October led to unprecedented law enforcement "heat," to public exposure and, ultimately, to the dismantling of the leadership of the New England Crime Family.

Disgraced by the Medford meeting and faced with serious racketeering charges as well as underworld insurrection, Patriarca stepped down. Nicholas Bianco, a Providence-based power who had not attended the Medford meeting, took over as boss for a short time. But Bianco got caught up in racketeering investigations sparked by the Grasso killing. He went off to start a long term in prison and soon died there. Patriarca pleaded guilty to racketeering and related charges. Consigliere Joseph Russo did the same. Crime family lieutenants, including Biagio DiGiacomo, Vincent Ferrara and Matthew Guglielmetti, also were sent to prison in the same period.

By the summer of 1991, the FBI's Boston office could identify just two strong figures in the crime family who were not disabled by recent criminal cases: Francis Salemme and Rhode Island resident Robert P. DeLuca. In mid-August, DeLuca was arrested. At that point, and largely by default, Salemme was in control of crime family operations. [3]

Salemme served as boss through just a few troubled years before he was forced to surrender the job. But there's much more to discuss about the "making" of "Cadillac Frank" before we turn our attention to his ruination.

Traditionally, the territory of the Patriarca Crime Family was the portion of New England east of the Connecticut River.

Francis Patrick Salemme was born August 18, 1933, in the Boston, Massachusetts, area. He was the second child and first son born to Romeo Pasquale and Mary Agnes Haverty Salemme. In the 1930s, the family resided in East Weymouth, about sixteen miles southeast of Boston, a community called home by a large extended family of Salemmes. [4]

By 1940, Romeo and Mary Agnes relocated their branch of the Salemme clan to Chestnut Avenue in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. Romeo was employed as a maintenance person for the Sears Roebuck Company, Brookline Avenue and Park Drive. (This was the Sears Roebuck building, constructed in 1928, that was converted into today's Landmark Center.) [5]

At the time of the 1950 U.S. Census, the Salemmes were residents of 11 St. John Street in Boston. Francis was sixteen. He may have been working at the time, but "ot" (other) is listed as his occupation. His siblings included a brother, John, and four sisters, Maryann, Judith, Elaine and Christine. [6]

Francis Salemme was twenty-two when he married nineteen-year-old Alice Kathleen McLaughlin on November 16, 1955. The couple went to Nashua, New Hampshire, sixty miles northwest of Boston, to be married.

For the marriage records, Francis reported that he was working as an electrician at that time. Alice was employed as a clerk. [7]

Francis Salemme

The decade of the 1960s was a violent time for Boston's gangland, and Francis Salemme contributed considerably to the bloodshed. Later in life, Salemme admitted that he was involved in killing eight people in the conflicts over organized crime territories. [8]

Three of those eight were the Bennett brothers. Edward "Wimpy" Bennett and siblings Walter and William were involved in rackets in the sprawling Dorchester area, reportedly operating out of headquarters in a busy Dudley Street night spot called Walter's Lounge. The lounge featured alcohol, live music and go-go girls, along with gambling, bookmaking, loansharking, etc. [9]

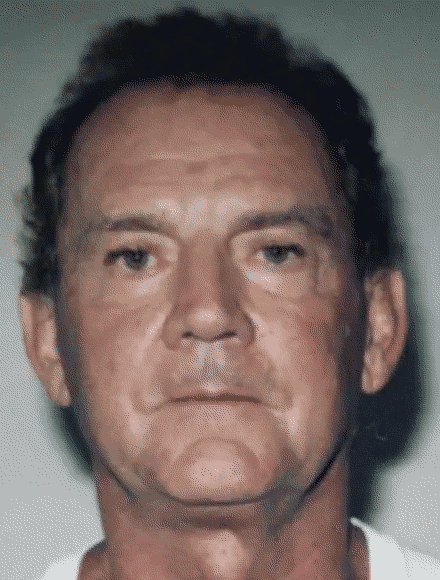

Bulger

According to some sources, the Bennetts were feuding with rising mafioso Ilario "Larry Baione" Zannino. Frank Salemme and his close friend Stephen "the Rifleman" Flemmi, who had strong ties to James "Whitey" Bulger's non-Mafia organization (often referred to as "the Winter Hill Gang"), reportedly eliminated the brothers as a favor to Zannino. Other sources suggest that Salemme and Flemmi merely wanted to take over Bennett rackets themselves or to gain them for Zannino's Mafia superiors, Boston leader Gennaro Angiulo or New England boss Raymond L.S. Patriarca. [10]

Wimpy was the first to go. Precisely where he went remains uncertain. He disappeared in January 1967. A few months later, Walter disappeared. (Almost immediately, FBI received reports that Salemme and Flemmi were responsible.) Informant Billy Geraway discussed the disappearances with a reporter some years later:

No one knows where Wimpy is. First they said he was in five feet of lime in Vermont. Then they said he was part of a bridge. They were lookin' for Walter down around Brockton under a dump. But the last thing I heard was that Walter was cut up and fed through a chicken feeder on a farm in New Hampshire. [11]

Wimpy Bennett

William took over for his brothers and unwisely let it be known that he was looking to avenge their deaths. Two days before Christmas, 1967, the lifeless body of William Bennett was tossed from a car on Harvard Street near Blue Hill Avenue. [12]

Authorities heard that Salemme and Flemmi had worked with several others - Robert Daddieco, Peter Poulos, Richard Grasso, Hugh Shields - in the murder of William Bennett. The fact that the dead William had not been made to vanish in the same manner as his brothers appeared to irk Salemme and Flemmi. As a consequence, Grasso was almost immediately murdered - after just a few days his remains were found in the trunk of his car in Brookline - and Poulos was reportedly killed at a later date and buried somewhere in the Nevada desert. [13]

Barboza

In about the same period, Joseph "the Animal" Barboza was turning on former colleagues in the New England Mafia and setting them up for prosecutors. He helped to frame a number of mobsters, including Henry Tameleo, Joseph Salvati and Peter Limone, for the March 1965 murder of career criminal Edward "Teddy" Deegan. Apparently disapproving of informants, Salemme decided to send a message to Barboza.

On January 30, 1968, Barboza's attorney John E. Fitzgerald Jr. started an automobile on Mansfield Street in Everett, Massachusetts. Two sticks of dynamite exploded beneath him. Fitzgerald survived the car-bomb but lost the lower portion of his right leg in the blast. [14]

As with the Bennett killings, Salemme's role in the attack on Fitzgerald was a poorly kept secret. Indictments were returned against him for both the murder of William Bennett and the car-bombing of Fitzgerald. But Cadillac Frank and Flemmi were suddenly missing.

In the autumn of 1969, the FBI began processing intel relating to the location of Salemme and Flemmi. An early report suggested that were hiding in Florida along with Luigi Manocchio and Frank "Vendi" Vendituoli. [15]

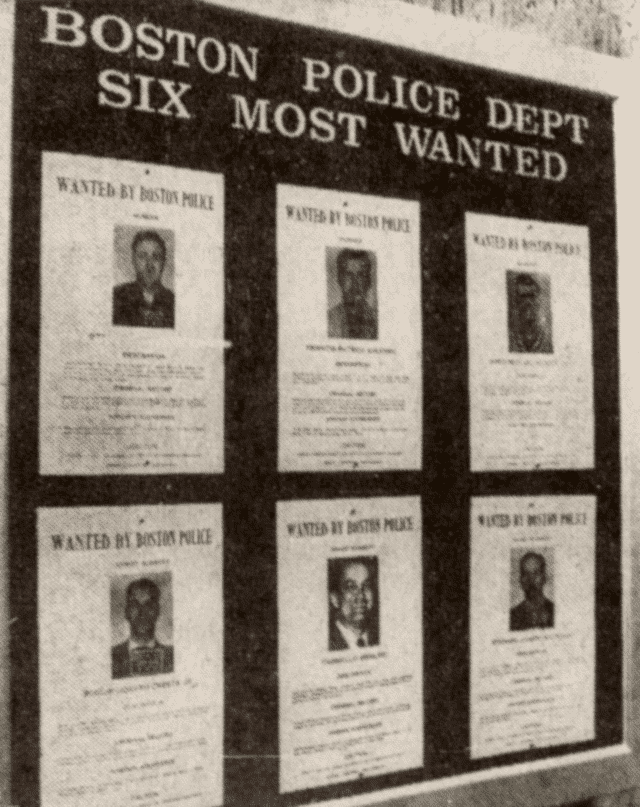

1970 Most Wanted (Boston Globe)

The following spring, Boston Police published a list of its six most wanted criminals. Stephen Flemmi, then thirty-five, and Francis Salemme, then thirty-six, occupied the first two positions on the list. [16]

While they were out of reach of the authorities, Hugh Shields, alleged accomplice in the William Bennett murder, was arrested. Shields and a Boston detective, William W. Stuart, were brought to trial in April 1970 in connection with the killing.

According to prosecutors, Shields and Richard Grasso were brought into the murder conspiracy because they were trusted friends of Bennett. They went to Bennett's home on the night of December 23, 1967, picked him up and drove him to a Dunkin Donuts shop nearby. During the drive back home, they shot him in the head and tossed his body out of the car.

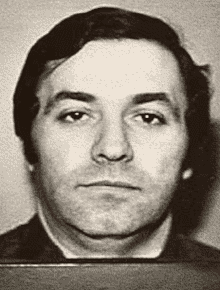

Flemmi

Prosecutors said Salemme, Flemmi, Daddieco and Poulos followed in a separate "cover car." After the killing, the six men got together, and Flemmi scolded Shields for dumping the body. The plan had been to keep Bennett until the other gangsters could verify his death and then to bury him. Shields reportedly said, "Don't worry, he's dead. I put four shots into him."

Flemmi did worry a bit, and prosecutors said he called on Detective Stuart to help him out. He had Stuart drive him to the location where Bennett had been dropped, so he could be assured that Bennett was dead. Later, he fed information to the detective about the location of Grasso's dead body. [17]

The state case would have been convincing except for the fact that its primary witness was Daddieco. A convicted felon recently released from Walpole State Prison, at the time of the Shields-Stuart trial Daddieco was facing charges of shooting a police officer during a holdup. The defense harshly criticized the prosecution's use of a career criminal in the case, particularly as one of the defendants was a police officer.

The Suffolk Superior Court jury deliberated for just over an hour on April 30 before deciding that both defendants were not guilty. [18]

Late in 1970 and early in 1971, the FBI was told that Francis Salemme and Stephen Flemmi were hiding with Luigi Manocchio near the Central Park area of New York City. [19]

It took agents until mid-December of 1972 before they could locate Salemme. They found him in apartment 15K at 353 East Eighty-third Street in Manhattan. Evidence suggested that Manocchio had also been at the address. At the time of Salemme's arrest, he was found to be in possession of the entire transcript of the Shields-Stuart trial. Salemme was charged with unlawful flight to avoid prosecution. He was processed in New York and then returned to the Boston area, where he faced charges in Suffolk County for the William Bennett murder and in Middlesex County for the Fitzgerald car-bombing. Flemmi remained at large. [20]

Salemme went to trial in Middlesex Superior Court on June 11, 1973. Represented by attorney F. Lee Bailey, he faced charges of armed assault to murder and assault and battery with a dangerous weapon, dynamite. After a one-week trial, the sixteen-person jury returned guilty verdicts on both counts. Judge Roger J. Donahue sentenced him June 19 to serve nineteen to twenty years in Walpole State Prison for the armed assault to murder charge and nine to ten years for the assault and battery charge. [21]

Boston Globe, June 20, 1973.

The Suffolk County murder trial was scheduled to begin on October 29, 1973. Two days before that, however, state star witness Robert Daddieco and all of his clothing disappeared from his apartment. Prosecutors postponed the trial.

A half year later, First Assistant District Attorney Lawrence Cameron went into Judge Walter H. McLaughlin's court to explain that his main witness against Salemme - a man who had been in federal protective custody - was still missing. The murder charge against Salemme was dropped. [22]

Salemme tried to fight the car-bombing conviction without success. The Massachusetts Appeals Court upheld the conviction in March 1975. The U.S. Court of Appeals considered the possibility that Salemme was found guilty by association - the names of known crime figures Gennaro Angiulo and Raymond Patriarca had been mentioned during his trial - but upheld the conviction in November 1978. Arguing that his defense attorney Bailey had a conflict of interest due to a relationship with bombing victim John Fitzgerald, Salemme moved in January 1979 for a new trial in Middlesex County. Judge Donahue refused. [23]

In July 1979, prison administrators decided that Salemme could leave Walpole to participate in the Medfield State Hospital Prison Project, in which prison inmates were put to work as mental health workers in the state's psychiatric facility.

Zannino

The assignment became a problem in April 1982, when Salemme was arrested leaving his home at Marie Avenue in Sharon. Alerted to reports that he was regularly leaving the hospital grounds and going home without authorization, state police and correction officers had been quietly keeping an eye on Cadillac Frank. When the violations became public knowledge, State Correction Commissioner Michael V. Fair promised an investigation. News reports indicated that Salemme faced an escape charge and additional prison time due to the misbehavior. But it is uncertain that he suffered any negative consequence. [24]

Salemme served about half of his possible twenty-eight- to thirty-year sentence. His 1987 release from prison was quickly followed by his formal induction into the New England Crime Family. [25]

The Boston branch of the criminal organization looked to have a special need for accomplished racketeers at that moment. In the later-1980s, successful federal prosecution had removed Hub-based underboss Gennaro Angiulo and his brothers Donato, Francesco and Michele (and a number of their underlings), as well as Gennaro Angiulo's lieutenant, Ilario "Larry Baione" Zannino. For about two decades, the Angiulos had been top earners for the Mafia, operating out of a Prince Street headquarters in the North End. [26]

Not long after the disastrous events of 1989, the Boston Globe reported an arrest of Salemme, "who survived an assassination attempt last year to emerge as the most powerful reputed Mafia figure in the Boston area." The statement oversimplified the process involved but accurately captured the suddenness of Salemme's gangland climb. [27]

The reported arrest sprang from a California charge of grand theft. According to prosecutors, Salemme and his son Frank Jr. "Frankie Boy" had left $56,000 of unpaid hotel and restaurant bills after a spring 1990 vacation in Los Angeles. The two Salemmes also were investigated by California authorities for wrongdoing involving the Teamsters union. Cadillac Frank was said to have siphoned off $10 million from a Teamsters pension fund. Frank Jr. was eventually indicted for attempting to bribe union officials to allow non-union employees to work on production of a movie. [28]

Bianco

Federal prosecutors in Connecticut played the tape recordings of the Medford induction ceremony during a July 1991 trial of eight crime family members. Among the defendants were Nicholas Bianco, the reigning New England boss, and Gaetano Milano, who was accused of murdering "Wild Guy" Grasso. [29]

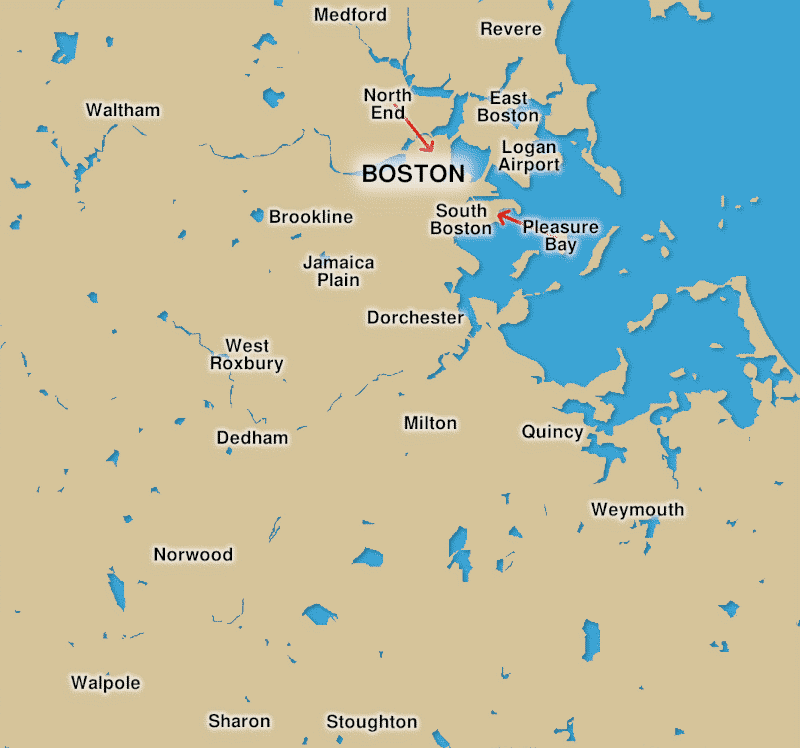

Days later, Cadillac Frank was spotted and photographed while huddling at Boston's Pleasure Bay beach with Robert DeLuca of Rhode Island and two mob associates. The Boston Globe published a photo in August and described its importance:

"The meeting is significant... without even knowing what was discussed because it represents a conversation between Patriarca representatives from the Boston and Providence areas at a time when leadership of the family could be up for grabs."

The same article quoted Dennis M. O'Callaghan, special agent with Boston's FBI field office:

"It's hard to say who actually maintains control. It's probably a little early to tell... Salemme certainly remains one of the more powerful and influential people still on the streets." [30]

"Junior" Patriarca

Bianco and his Connecticut codefendants were convicted of racketeering violations in August. The official designation of Salemme as the new crime family boss probably occurred at about the same time. Bianco was sentenced in November to a prison term of eleven years and five months. The judge allowed him to spend the holiday season with his family by setting the start date of the sentence at December 30, 1991. [31]

Between Bianco's sentencing and the start of his prison term, Salemme was overheard telling a underworld colleague from out of town, "I'm the boss." [32]

Russo

On December 3, "Junior" Patriarca reached a plea deal in Boston. He pleaded guilty to racketeering, interstate travel in aid of racketeering and racketeering conspiracy. He acknowledged his former leadership of a criminal organization but refused to go on record admitting the existence of the Mafia criminal society. Patriarca stated, "By admitting my guilt, I am not admitting my membership in the Mafia." This denial nearly caused prosecutors to back out of their deal, but Judge Mark Wolf pointed out that Patriarca's plea indicated his organization was "substantially similar" to the Mafia. [33]

Joseph Russo and four codefendants entered guilty pleas on January 22, 1992, after the Medford recordings were played in Boston's federal court. All five admitted to racketeering-related charges, including murder, kidnapping, extortion, gambling and narcotics trafficking, while denying that they were members of an organization known as "Mafia," "La Cosa Nostra" or "the Patriarca Crime Family." Russo did not admit to the February 1967 killing of turncoat Joseph Barboza, but accepted that there was sufficient evidence to prove him guilty of that charge.

The Boston Globe reported that "the guilty pleas leave Frank (Cadillac Frank) Salemme of Sharon... as the heir apparent to leadership of the Mafia in New England. Federal officials acknowledge Salemme's increased influence but would neither officially confirm nor deny that he is now the boss of the regional La Cosa Nostra." [34]

Salemme's quick leap to the top of the Mafia hierarchy represented a dramatic shift for the New England Crime Family. Since the 1950s, when Raymond L.S. Patriarca took over for Filippo Buccola, crime family bosses had been based in Providence. With Salemme's accession, the regional Mafia capital moved (momentarily) back to Boston. [35]

The sudden absence of so many underworld leaders from Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts, left organized crime investigators with little to do besides examine Cadillac Frank. One of the things they found interesting was Salemme's rumored investment in a South Boston nightclub called The Channel. FBI agents began questioning club manager Steven A. DiSarro. The questioning stopped abruptly in May 1993, as DiSarro, the forty-three-year-old father of five children, went missing. [36]

"Whitey" Bulger

The Salemme regime experienced about nineteen months of relative peace between the middle of 1993 and the start of 1995, and appears in this time to have further refined the Mafia's long-term cooperation with the well-connected non-Mafia organization of James "Whitey" Bulger in South Boston. Salemme and Bulger had a working relationship that extended back to the 1960s and a racket-sharing agreement that was ironed out in the 1970s. [37] Francis Salemme suffered a personal loss in the February 20, 1994, death of his father. The November 14, 1994, death of incarcerated ex-boss Nicholas Bianco may have been an unwelcome surprise but may have served to strengthen Salemme's hold on the crime family. [38]

The organization was jolted in January 1995 by a "sweeping racketeering case" brought by federal authorities against Francis Salemme, "Whitey" Bulger and others. A federal grand jury indictment was revealed on January 10, but Salemme and Bulger had been tipped off days earlier by FBI agent John J. Connolly Jr. Both fled New England before law enforcement could be sent to collect them. [39]

The initial indictment charged sixty-one-year-old Salemme with two counts of racketeering, seven counts of extortion, five counts of crossing state lines for criminal activity, one count of conspiracy and one count of loansharking. Bulger, then sixty-five, was charged with two counts of racketeering and ten counts of extortion.

Also indicted were James Martorano (racketeering, extortion conspiracy), Robert DeLuca (racketeering, extortion, conspiracy, crossing state lines), Stephen Flemmi (racketeering, extortion, witness tampering), George Kaufman (racketeering, extortion, money laundering) and Frank Salemme Jr. (racketeering, crossing state liens, conspiracy, extortion).

In the case, the government for the first time charged that the New England Mafia and the Bulger organization had entered into an agreement through which they coordinated criminal enterprises, such as the collection of "rent" payoffs from bookmaking operations. [40]

Salemme eluded police for months. Son Frank Jr., facing a number of criminal charges on both U.S. coasts, was never brought to trial. He became very ill and was diagnosed with lymphoma. Frank Jr. died June 23, 1995, at his home in Sharon. He was thirty-eight. Services were conducted at the Keeling-Tracy Funeral Home in Walpole, and Frank Jr. was buried at Rock Ridge Cemetery in Sharon. Cadillac Frank reportedly elected to remain in hiding rather than attend his son's funeral. [41]

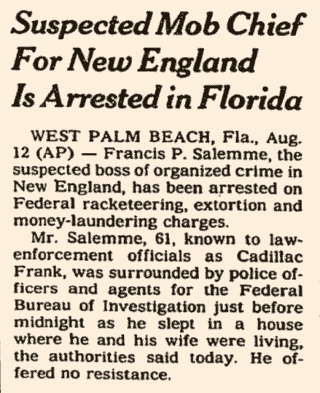

NY Times, Aug. 13, 1995.

Television eventually exposed Francis Salemme. He was featured on an episode of the America's Most Wanted program, and a number of viewers tipped authorities that he had been seen in the West Palm Beach area of Florida. On the night of August 12, 1995, law enforcement arrested Salemme at a rented townhouse in West Palm Beach's Sandalwood Lakes Village. He was processed before a federal magistrate in Fort Lauderdale and returned to Boston. (Bulger remained in hiding for more than sixteen years, until his arrest in Santa Monica, California, on June 22, 2011.) [42]

If Salemme's disappearance did not end his career as Mafia boss, then the lengthy stay in jail following his arrest surely did. Sometime around 1995-1996, Luigi Manocchio of Rhode Island appears to have taken charge of the crime family.

During the lengthy preparations for his trial, Salemme became aware that his old friends Bulger and Flemmi had been cooperating secretly with federal agents since the 1970s. Working primarily with agent Connolly, they provided the feds information about mafiosi, including Salemme.

Flemmi's defense counsel argued in federal court that the FBI assured him and Bulger that they could continue racketeering without penalty as long as the activities did not involve (additional) murders and they continued to cooperate in investigations. Federal Judge Mark Wolf looked into the FBI-gangland agreement and ruled that it did not prevent prosecution of Flemmi and Bulger. [43]

Salemme remained in jail while his attorney attempted without success to have FBI electronic surveillance evidence thrown out. A listening device picked up Salemme's "I'm the boss" remark back in December 1991. That statement was made at the Logan Airport Hilton in a conversation between Salemme and visiting Gambino Crime Family bigshot Natale "Big Chris" Richichi. During the discussion, Salemme also mentioned Bulger and Flemmi by name as men who supported him. [44]

While the Mafia boss was working to have evidence and charges removed from the case, prosecutors went to the grand jury to have the 1967 murders of the Bennett brothers and Richard Grasso added to the case.

After more than four years of unproductive legal challenges, Cadillac Frank decided on December 9, 1999, that it was enough. He went to the witness stand in Judge Mark Wolf's courtroom and pleaded guilty to fifteen counts of racketeering, extortion, bribery and interstate travel in aid of racketeering. He specifically admitted to arranging a pact with Bulger to extort "rent" from bookmakers, loansharks and drug dealers and indicated the arrangement was in place from 1979 through 1994. The four 1967 murder charges against him were dropped.

Salemme reported told the judge he was done with racketeering:

"I want no part of anything ever again... I've learned my lesson. Shame on me if it happens again."

In exchange for his guilty plea, prosecutors asked the court for a prison sentence greater than ten years and ten months and less than thirteen years and six months. He was sentenced to eleven years, but had already served nearly half that awaiting trial. [45]

A federal grand jury on Wednesday, December 22, 1999, indicted FBI agent John J. Connolly Jr. on five counts relating to his cooperation with and protection of his underworld informants Bulger and Flemmi. The focus of the indictment was Connolly's January 1995 warning to the pair that they were about to be charged with federal racketeering offenses.

A report indicated that Francis Salemme testified before the grand jury investigating Connolly. It appeared that the Mafia boss who wouldn't even give his name to the authorities years earlier had become more talkative with age. [46]

In fact, Salemme began to provide law enforcement with information on his old friends Bulger and Flemmi as well. After settling the score with the mobsters who had provided information against him, however, Salemme seems not to have gone any further.

His information was sufficient to cause him to be released from prison into the witness protection program in 2003. He was soon ejected from the program, when law enforcement charged that he lied to cover up his son's role in the May 1993 disappearance of The Channel nightclub manager Steven DiSarro. A charge of obstruction of justice was lodged against him. [47]

More years of pretrial legal wrangling followed. Salemme learned that federal agents had obtained information in 2003 that Frank Salemme Jr. had choked Steven DiSarro to death in the presence of Salemme and others in order to prevent DiSarro cooperation with federal investigators. No charges had been filed in the case because Frank Jr. was already dead, DiSarro's body was missing and other connections could not be proved.

In February 2008, Cadillac Frank reached an agreement with prosecutors. While he pleaded guilty to lying to agents and obstructing justice to protect his son, he refused to admit that he personally watched his son strangle DiSarro. Salemme suggested that he had no problems with DiSarro but understood that a former New England boss, the late Nicholas Bianco, had some trouble with the nightclub manager.

This plea deal called for sixty-one to sixty-three months in prison minus time already served. As Salemme by that time had been held in jail for years, the sentence allowed his release around the end of 2008.

At sentencing, Salemme stated, "I want to categorically deny that I had anything to do with DiSarro, the assault or the murder." [48]

Francis Salemme

Eighty-two-year-old Cadillac Frank was experiencing quiet retirement at the start of 2016. He had returned to the witness protection program and was a resident of the Atlanta, Georgia, area, using the name Richard Parker. (He reportedly used the alias when signing up remotely for a New England Patriots fan club.) That would have been the peaceful final chapter of his biography if not for the legal problems of a mob-linked businessman a thousand miles away. [49]

The owner of a mill business at 715 Branch Avenue near Woodward Road in Providence, Rhode Island, ran into some trouble with the law. William Ricci, the owner, was described as a Mafia associate close to mobster Robert DeLuca. He reportedly attempted to reduce the severity of the charges against him by offering authorities some information: decades earlier, a body had been buried on the property behind his mill. Ricci was subsequently charged with permitting others to use his property for a large-scale marijuana-growing operation. Two other charges were dropped due to his cooperation. [50]

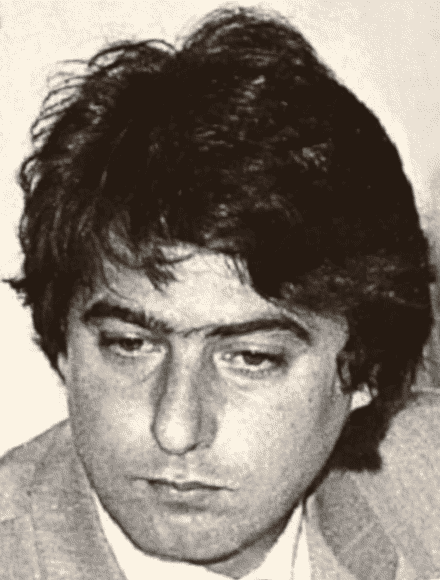

DiSarro

Ricci's information prompted law enforcement near the end of March 2016 to begin a massive excavation project. Word of the digging at the mill site quickly reached Salemme in Atlanta. Once again, he disappeared. [51]

After three days of digging, on March 31, a body was exhumed from the mill property. The body was turned over to the Rhode Island Medical Examiner's Office in the hope that it could be identified. Testing and DNA analysis provided an answer on June 9. It was Steven A. DiSarro. [52]

The circumstances of DiSarro's burial were found to be entirely in agreement with information supplied to state and federal investigators in 2003 by Stephen Flemmi. That account was contrary to the story told by Salemme. Agents reached the conclusions that Flemmi's account should be more carefully examined and that Cadillac Frank had lied again.

In a statement preserved in a Drug Enforcement Administration report, Flemmi stated that he stopped by the Salemme home in Sharon and found Frank Jr. strangling DiSarro while Francis Salemme, his brother John Salemme and friend Paul Weadick looked on. Frank Jr. was behind the nightclub manager and lifting him off the floor with arms wrapped around his neck. Flemmi said he quickly left the house but was later told by Cadillac Frank that DiSarro was killed due to concerns over a federal investigation. A friend of DiSarro's was already believed to be providing agents with information. Salemme also told Flemmi that Rhode Island mobster Robert DeLuca was present for the burial of DiSarro's body at a Providence construction site. [53]

DeLuca, who told investigators in 2011 that he knew nothing of DiSarro's disappearance, was indicted June 23, 2016, for obstruction of justice and two counts of making false statements. Four days later, federal agents Rhode Island and Massachusetts State Police arrested DeLuca at Broward County, Florida. He was returned to Boston and held without bail. [54]

Salemme was tracked to Connecticut and arrested at a hotel there on August 10. He was brought back to Boston in handcuffs. He and Paul Weadick were indicted September 2 for the murder of DiSarro, classified as a witness in a federal investigation. [55]

The case against Salemme and Weadick went to trial in June of 2018. Using testimony from Flemmi and from the cooperating DeLuca brothers of Rhode Island, prosecutors argued that Francis Salemme watched his son murder DiSarro, while Weadick helped hold the struggling victim's legs.

Turncoat Robert DeLuca testified to a new motive in the DiSarro slaying. He said Salemme informed him that DiSarro was stealing from the income of The Channel. According to DeLuca, Salemme called him the day before DiSarro's disappearance and ordered him to prepare: "Make sure you've got a hole dug and some lime... I'll be down with a package." DeLuca had his brother and others waiting at the site when Salemme arrived with the "package."

A federal jury deliberated for four days before deciding on June 22 that both defendants were guilty of murdering a federal witness. The two men received mandatory life prison sentences. [56]

Boston Globe, June 23, 2018.

Cadillac Frank was not quite eighty-five at the time of his last criminal conviction. Shortly after beginning his federal prison sentence, due to his age, he was transfered to the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners at Springfield, Missouri. [57]

He died at the Springfield facility on Tuesday, December 13, 2022. He was eighty-nine years old. No official cause of death was stated.

News of Salemme's passing was released slowly. Steven DiSarro's son Nick reportedly became aware of it on Sunday, December 18, when he received an email notification from a service that alerts the families of victims to news of federal inmates.

Attorney Steven C. Boozang, who represented Salemme through his last trial, said he thought Salemme "regretted a lot of things in his life... I think he felt particularly bad for the hardship that came to his family and to other families."

Boozang noted that Salemme, for the most part, remained true to his friends. While he possessed information that could have put many behind bars, he limited his cooperation to government cases against those who played both sides: "He could have hurt a lot of people but chose not to."

Speaking with reporters, Nick DiSarro said he felt "the world is a better place without [Salemme] in it." [58]

1 Cullen, Kevin, "Two men linked to mob shot in separate attacks," Boston Globe, June 17, 1989, bostonglobe.com; Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.

See also Hunt, Thomas, "Top New England mobsters targeted," Writers of Wrongs, writersofwrongs.com, June 16, 2018.

2 "Jury hears tapes of Mafia induction ceremony," AP, apnews.com, July 4, 1991.

3 Hernandez, Efrain Jr., "Convictions, trials cloud Mafia's future," Boston Globe, Aug. 16, 1991, p. 1; "Reputed Patriarca boss to begin sentence Monday," Boston Globe, Dec. 28, 1991, p. 30; Rakowsky, Judy, "Nicholas Bianco, 69, in prison; considered a crime family leader," Boston Globe, Nov. 15, 1994, p. 63.

There is some suggestion in the reporting that important Mafia figures from New York became involved in the matter and forced Raymond J. Patriarca to step down. Rakowsky's obituary notes that Bianco had been groomed as Raymond L.S. Patriarca's successor, but when the moment arrived for his accession, "Junior" Patriarca somehow found support to take the boss job for himself.

4 Francis P. Salemme, U.S. Public Records Index 1950-1993, Vol. 2, Ancestry.com; Index to Births in Massachusetts 1931-1935, Pozzani-Stallings, Volume 132, Boston: Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Health Registry of Vital Records and Statistics, Ancestry.com; United States Census of 1940, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Boston, Jamaica Plain, Ward 19, Enumeration District 15-663.

Francis Salemme's paternal grandfather, Alessio Salemme, reached the U.S. aboard the S.S. Neustria in May 1891 - sometimes shown as May 1892. (He sailed under the name Alessio Apicella.) The family roots extend back to Mirabella Eclano, Avellino Province, Campania, Italy, which lies about 50 miles inland of Naples. Alessio and his wife, Anna Caponi, settled in East Weymouth, where Alessio worked for the Stetson Shoe Company. They had ten children there. The longtime family home was located at 47 Lake Street.

There is an oddity relating to the birth of Francis Salemme's father, Romeo Pasquale. While his birth is placed on Aug. 12, 1909, Romeo does not appear in the family's listing in the 1910 Census. The document states that Anna gave birth to five children and had four children living. The living children were shown as Peter, John, Ralph and Alice. Romeo appears in the family listings in the 1920 and 1930 censuses, though Alice is not seen. (Romeo's 1908 birth and 1911 baptism appear to have been documented by the Catholic archdiocese on December 17, 1911.) See: "Patricium, Romeo Pasquale, Patrick Solemme," Boston Massachusetts Archdiocese Roman Catholic Sacramental Records, 1789-1920, Ancestry.com; United States Census of 1910, Massachusetts, Norfolk County, Weymouth, Ward 2, Precinct 6, Enumeration District 1167; United States Census of 1920, Massachusetts, Norfolk County, Weymouth, Enumeration District 280; United States Census of 1930, Massachusetts, Norfolk County, Weymouth, East Weymouth, Enumeration District 11-141.

5 United States Census of 1940, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Boston, Jamaica Plain, Ward 19, Enumeration District 15-663; Romeo Patrick Salemme World War II Draft Registration Card, serial no. 56, order no. 1027, Local Board no. 35, Jamaica Plain, Suffolk County, Massachusetts, Oct. 16, 1940.

6 United States Census of 1950, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Boston, Enumeration District 15-1091.

7 Francis Patrick Salemme and Alice Kathleen McLaughlin, Certificate of Intention of Marriage, no. 55-6206, Nashua, NH, filed Nov. 22, 1955.

8 Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.

9 Smith, Anson, "Conversations with a stool pigeon," Boston Globe Sunday magazine, May 12, 1974, p. 6; "1969 murder charge dismissed against Walpole inmate," Boston Globe, April 22, 1974, p. 23; Gelzinis, Peter, "Feds betray Bennett family once again," Boston Herald, bostonherald.com, July 6, 2000.

10 Sullivan, Thomas H., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI report of Boston office, file no. 92-6054-2100, NARA no. 124-10293-10336, Sept. 11, 1967, p. 7; Smith, Anson, "Conversations with a stool pigeon," Boston Globe Sunday magazine, May 12, 1974, p. 6; "Angiulos linked to more murders," Athol MA Daily News, Nov. 20, 1985, p. 10.

11 Smith, Anson, "Conversations with a stool pigeon," Boston Globe Sunday magazine, May 12, 1974, p. 6.

12 "1969 murder charge dismissed against Walpole inmate," Boston Globe, April 22, 1974, p. 23; Gelzinis, Peter, "Feds betray Bennett family once again," Boston Herald, bostonherald.com, July 6, 2000.

13 Walsh, Robert E., "State names triggerman, links detective in slaying," Boston Globe, April 14, 1970, p. 14; "Suspect in gangland death caught," Boston Globe, Sept. 20, 1969, p. 22; "1969 murder charge dismissed against Walpole inmate," Boston Globe, April 22, 1974, p. 23.

14 Wysocki, Ronald A., "Two fugitives indicted for bombing," Boston Globe, Oct. 10, 1969, p. 1; Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.

15 McWeeney, Sean M., "Luigi Giovanni Manocchio...," FBI report of Boston office, file no. 166-4355-42, NARA no. 124-10212-10062, Oct. 23, 1969, p. Cover-P.

16 "Boston police issue '6 most wanted' list," Boston Globe, April 1, 1970, p. 3.

17 "Suspect in gangland death caught," Boston Globe, Sept. 20, 1969, p. 22; Wysocki, Ronald, "Officer tied to murder," Boston Globe, Feb. 19, 1970, p. 1; "Hub officer indicted in gang killing," Boston Globe, Feb. 20, 1970, p. 4; Walsh, Robert E., "State names triggerman, links detective in slaying," Boston Globe, April 14, 1970, p. 14.

18 Walsh, Robert E., "Detective, S. Boston man acquitted in gangland murder case," Boston Globe, May 1, 1970, p. 14.

19 Reppucci, Charles A., "Luigi Giovanni Manocchio...," FBI report of Boston office, file no. 166-4355-101, NARA no. 124-10207-10271, Jan. 29, 1971, p. Cover-B-C.

20 "Hub suspect held in NYC," Boston Globe, Dec. 15, 1972, p. 6; SAC Boston, "Luigi Manocchio... Stephen Joseph Flemmi... Francis Patrick Salemme," FBI memorandum, Jan. 4, 1973, p. 2; "1969 murder charge dismissed against Walpole inmate," Boston Globe, April 22, 1974, p. 23; SAC Boston, "Luigi Manocchio... Stephen Joseph Flemmi... Francis Patrick Salemme," FBI memorandum, Jan. 4, 1973, p. 1-2.

21 "Jurors chosen as Salemme trial opens," Boston Globe, June 11, 1975, p. 5; "Sharon man found guilty of car bombing," Boston Globe, June 16, 1973, p. 3; O'Donoghue, Edward, "Salemme guilty of attempted murder of Everett attorney, sentence delayed," Lowell MA Sun, June 16, 1973; Brine, Dexter, "28 years for bomber Salemme," Boston Globe, June 19, 1973, p. 5.

22 "1969 murder charge dismissed against Walpole inmate," Boston Globe, April 22, 1974, p. 23.

23 "'68 auto blast," Boston Globe, March 4, 1975, p. 11; "US court upholds bombing conviction," Boston Globe, Nov. 23, 1978, p. 22; "Salemme loses bid for second trial," Boston Globe, Jan. 10, 1979, p. 1.

24 "Reputed mob figure faces escape charge in home visit," Boston Globe, April 29, 1982, p. 21; Flaherty, Tim, "A look back at Medfield State Hospital," Wicked Local, wickedlocal.com, May 8, 2015.

25 Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022; Burnstein, Scott, "The downfall of a don: fresh intel on how Patriarca, Jr. lost grip of New England Mafia in '89," Gangster Report, gangsterreport.com, June 2018.

26 Murphy, Shelley, and Megan Trench, "Ex-mob boss to be freed Sept. 18," Boston Globe, July 7, 2007; "Reputed mob boss awaits sentencing," Holyoke MA Transcript-Telegram, March 7, 1987, p. 3; Bredice, Steven, "Mafia lieutenant sentenced to 30 years in prison," Berkshire Eagle, March 13, 1987, p. 4.

27 Cullen, Kevin, "Reputed mob figure held on Calif. charge," Boston Globe, Dec. 14, 1990, p. 37.

28 Cullen, Kevin, "Reputed mob figure held on Calif. charge," Boston Globe, Dec. 14, 1990, p. 37; Wong, Doris Sue, "Salemmes ordered to Calif. to face theft charges," Boston Globe, April 5, 1991, p. 1; "Son of reputed Mafia boss dies," Boston Globe, June 24, 1995, p. 24

29 "Jury hears tapes of Mafia induction ceremony," AP, apnews.com, July 4, 1991.

30 Hernandez, Efrain Jr., "Convictions, trials cloud Mafia's future," Boston Globe, Aug. 16, 1991, p. 1.

31 Hernandez, Efrain Jr., "Crime boss Bianco gets 11-year term," Boston Globe, Nov. 26, 1991, p. 17; "Reputed Patriarca boss to begin sentence Monday," Boston Globe, Dec. 28, 1991, p. 30.

32 Murphy, Shelley, "Mafia leaders still don't know when to shut up," Boston Globe, Jan. 11, 1995, p. 1.

33 Murphy, Sean P., "Patriarca pleads guilty to racketeering," Boston Globe, Dec. 4, 1991, p. 1; Blake, Andrew, "Mafia power shifts with five guilty pleas," Boston Globe, Jan. 23, 1992, p. 1.

34 Blake, Andrew, "Mafia power shifts with five guilty pleas," Boston Globe, Jan. 23, 1992, p. 1.

35 Blake, Andrew, "Mafia power shifts with five guilty pleas," Boston Globe, Jan. 23, 1992, p. 1.

36 "Former Mafia boss and associate convicted of 1993 murder," press release of U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts, June 22, 2018.

37 Murphy, Shelley, "Mafia leaders still don't know when to shut up," Boston Globe, Jan. 11, 1995, p. 1.; Murphy, Shelley, "Salemme pleads guilty to racketeering," Boston Globe, Dec. 10, 1999, p. B4.

38 Romeo P. Salemme, Massachusetts Death Index 1970-2003, Feb. 20, 1994, Ancestry.com; Rakowsky, Judy, "Nicholas Bianco, 69, in prison; considered a crime family leader," Boston Globe, Nov. 15, 1994, p. 63; Murphy, Shelley, "Former mob boss gets 5 years for lying, obstruction," Boston Globe, July 16, 2008.

Nicholas Bianco reportedly was afflicted with Lou Gehrig's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

39 "Former New England mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dead at 89, Target-12-WPRI, wpri.com, Dec. 18, 2022; Radowsky, Judy, and Matthew Brelis, "US panel indicts Bulger, Salemme," Boston Globe, Jan. 11, 1995, p. 1; Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.

40 Radowsky, Judy, and Matthew Brelis, "US panel indicts Bulger, Salemme," Boston Globe, Jan. 11, 1995, p. 1;

41 "Son of reputed Mafia boss dies," Boston Globe, June 24, 1995, p. 24; "Salemme," Boston Globe, June 25, 1995, p. 71.

42 "Suspected mob chief for New England is arrested in Florida," New York Times, Aug. 13, 1995; "FBI arrests mob suspect after 2 years," Tampa Tribune, Aug. 13, 1995, p. Metro-2; Staletovich, Jenny, "Reputed mob boss arrested," Palm Beach FL Post, Aug. 13, 1995, p. 1.

43 Murphy, Shelley, "Judge to focus on Salemme's challenge against allegations," Boston Globe, Sept. 17, 1999, p. B6.

44 Murphy, Shelley, "Judge to focus on Salemme's challenge against allegations," Boston Globe, Sept. 17, 1999, p. B6.

45 "Former Mafia boss and associate convicted of 1993 murder," press release of U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts, June 22, 2018; Murphy, Shelley, "Salemme pleads guilty to racketeering," Boston Globe, Dec. 10, 1999, p. B4; McDougall, A.J., "Ex-Mafia don 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies behind bars at 89," Daily Beast, Dec. 19, 2022.

46 Murphy, Shelley, and Judy Rakowsky, "Former star FBI agent is charged," Boston Globe, Dec. 23, 1999, p. 1; Murphy, Shelley, "Plea agreement could free ex-mob boss by year-end," Boston Globe, Feb. 27, 2008.

47 Murphy, Shelley, "Plea agreement could free ex-mob boss by year-end," Boston Globe, Feb. 27, 2008.

48 "Former Mafia boss and associate convicted of 1993 murder," press release of U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts, June 22, 2018; Murphy, Shelley, "Former mob boss gets 5 years for lying, obstruction," Boston Globe, July 16, 2008; Murphy, Shelley, "Plea agreement could free ex-mob boss by year-end," Boston Globe, Feb. 27, 2008.

49 "Former New England mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dead at 89, Target-12-WPRI, wpri.com, Dec. 18, 2022; Betz, Bradford, "New England ex-mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," FoxNews, Dec. 18, 2022.

50 Murphy, Shelley, and Travis Anderson, "Two decades on, FBI digs for a mob victim," Boston Globe, March 31, 2016, p. B1; Amaral, Brian, "'Cadillac Frank' Salemme found guilty in 1933 murder of Providence native," Providence Journal, June 22, 2018.

51 Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.

52 Anderson, Travis, and Shelley Murphy, "Human remains found at Providence site," Boston Globe, April 1, 2016, p. B1; Anderson, Travis, and Shelley Murphy, "Remains identified as missing Mass. man," Boston Globe, June 10, 2016, p. B1.

53 Murphy, Shelley, "Charge upends ex-mobster's new life," Boston Globe, Aug. 11, 2016, p. 1.

54 Murphy, Shelley, "R.I. mobster charged with hindering probe of '93 murder," Boston Globe, June 29, 2016, p. B3; Ellement, John R., "No bail for R.I. man accused of lying about killing," Boston Globe, July 9, 2016, p. 5.

55 Murphy, Shelley, "Charge upends ex-mobster's new life," Boston Globe, Aug. 11, 2016, p. 1; Murphy, Shelley, "2nd man charged in slaying of club owner," Boston Globe, Sept. 3, 2016, p. 2.

56 Murphy, Shelley, "Mobster recalls 'little talk' with Salemme," Boston Globe, May 30, 2018, p. B1; "Former Mafia boss and associate convicted of 1993 murder," press release of U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts, June 22, 2018; Amaral, Brian, "'Cadillac Frank' Salemme found guilty in 1933 murder of Providence native," Providence Journal, June 22, 2018; Dumcius, Gintautas, "Former New England Mafia boss Francis 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme found guilty," MassLive, masslive.com, June 22, 2018; Richer, Alanna Durkin, "Ex-New England Mafia boss 'Cadillac Frank' guilty in slaying," Boston.com, June 22, 2018.

See also: Hunt, Thomas, "Ex-boss Salemme, 84, convicted of murder," Writers of Wrongs, writersofwrongs.com, June 23, 2018.

57 Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.

58 Francis P. Salemme, register no. 24914-013, Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator, bop.gov; "Ex-New England Mafia boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," New York Post, Dec. 18, 2022; "Former Mafia boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," CBS News, cbsnews.com, Dec. 18, 2022; "Former New England mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dead at 89, Target-12-WPRI, wpri.com, Dec. 18, 2022; Stoico, Nick, and Shelley Murphy, "Former mob boss 'Cadillac Frank' Salemme dies in prison at 89," Boston Globe, bostonglobe.com, Dec. 18, 2022.