This article was originally written in 2019. It was edited and reformatted in February 2022.

A widely publicized south Florida prizefight led to the names of Salvatore "Charlie Luciano" Lucania and Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria appearing together in print in February 1930.

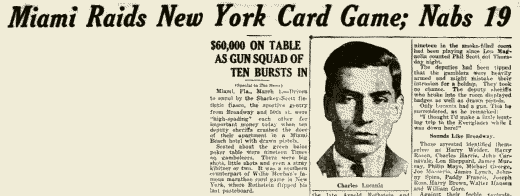

Early in the morning of Friday, February 28,[1] Dade County Sheriff Manuel Philip Lehman received a tip that a number of men from out of town were gambling in a top-floor suite of a Miami Beach hotel. Lehman and ten of his deputies raided the location. Warned that the gamblers might be armed, they burst inside with their weapons drawn.[2]

New York Daily News.

They found eighteen men[3] around gaming tables and arrested them. Deputies gathered up a total of $73,575.05 in cash and a single handgun. The weapon and most of the cash - more than $60,000 of it - were taken from a single thirty-two-year-old New York gambler. That individual, who gave authorities the name "Charles Lucania," was believed to be the organizer of the gambling event. (Born Salvatore Lucania, he generally used the first name "Charlie" and was referred to by criminal associates as "Lucky." Police and press appear to have later distorted his surname into the more widely known "Luciano.")

The quantity of cash seized in the raid was extraordinary for the period. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, a dollar in 1930 was roughly equivalent to sixteen or more dollars today. That puts the raid total in line with about $1.2 million in 2022 dollars. Lucania's personal pile of bills would amount to about $960,000 today. (See CPI Inflation Calculator, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov.)

The New York Daily News reported on the raid and on Lucania's earlier known underworld connections:

"A swarthy young chap with an ugly scar from his left ear to his collar held a roll of money that resembled a cabbage head. There was $60,090 in the bundle, and its owner, the game's banker, was Charles (Lucky) Lucania, a pal of the late Arnold Rothstein's and Jack (Legs) Diamond's."[4]

St. Louis Star.

The other arrested gamblers in the hotel suite were found in possession of amounts of cash ranging from as much as $5,000 to as little as twelve cents.

The arrested men were identified as:

Giuseppi "Joe" Masseria had risen to command a Manhattan-based Mafia organization (known decades later as the Genovese Crime Family). Masseria became the U.S. Mafia's boss of bosses late in 1928, following the murder of his longtime rival Salvatore "Toto" D'Aquila.[6] At the time of this 1930 arrest, the Mafia was experiencing the first rumblings of what would become a widespread revolt against Masseria's leadership, a conflict known as the Castellammarese War. The John Masseria shown on the list was likely Giuseppe Masseria's brother John, who was active in the Sicilian-American underworlds of New York City and Cleveland, Ohio.

One other man, said to be Frank Jacone of New York, was arrested when he came to the Dade County Jail and attempted to secure the release of the prisoners on bail. [7]

Lucania

All were questioned, fingerprinted and photographed, individually and in a group. When Lucania was asked about his possession of a handgun, he responded, "I thought I'd make a little hunting trip to the Everglades while I was down here."[8]

The men were charged with vagrancy and gambling. Lucania was charged with running a gambling house and with carrying a concealed firearm. Once the authorities sorted out the relationships among the suspects and found "Joe the Boss" to be Lucania's superior, Masseria also was charged with running a gambling house.

News of the arrests were kept secret through most of Friday, as the suspects were processed. When the raid and its results were announced, the sheriff's office indicated that the gambling event was scheduled to coincide with the Jack Sharkey-Phil Scott heavyweight boxing match of Thursday night, February 27.[9]

(Chicago gang boss Al Capone, a seasonal Miami Beach resident and underworld ally of Masseria and Lucania, would have been a likely attendee at such an event, but Capone was finishing a prison term in Pennsylvania at the time. He was not released until March 17, 1930.)[10]

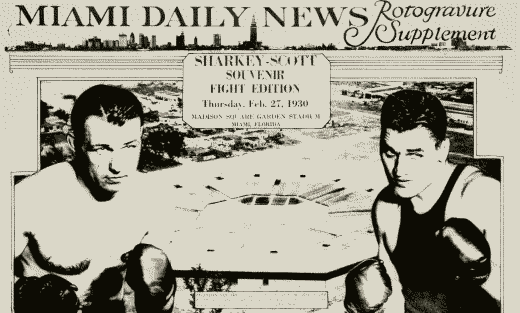

The gamblers and thousands of sports fans had assembled for the second annual Battle of Miami boxing event put on in Miami, Florida, by the New York-based Madison Square Garden Company. The February 27 event was generally deemed a sporting and financial failure.

The 52,000-seat octagonal wooden arena at N.W. Twenty-eighth Street and Eighth Avenue welcomed just 18,600 fans to the boxing match. Gate receipts were $190,000, far short of $300,000 hoped for by management. (The first event at Flamingo Park in Miami Beach a year earlier drew 30,000 fans and brought in $407,000.) Estimates of Madison Square Garden financial losses from the single event ranged from $50,000 to $75,000.

Miami Daily News.

Almost half of the gate receipts were promised to the competitors in the featured match, heavyweight contenders Jack "Boston Gob" Sharkey and British champion Phil Scott. Sharkey, born in Binghamton, New York, and raised in Boston, took twenty-five percent. Scott took twenty.[11]

Weeks before the fight, there were reports that Scott was out of shape and having trouble getting used to the south Florida climate. Sharkey, who defeated Young Stribling on points at the Flamingo Park event in 1929, had no such difficulties.[12]

Promoters did their best to counter the public impression that the fight was a mismatch and to add significance (and attendance) to the event. A lengthy newspaper article by Damon Runyon discussed Phil Scott's workouts and praised the British boxer's stamina and powerful punch. Promoters announced that the winner of the Sharkey-Scott fight would move on to battle heavyweight champion Max Schmeling for the title in June. The Madison Square Garden Company prevented the broadcast of the fight on radio. On the eve of the event, in what looked to be a last-ditch effort to heighten fan interest, newspapers reported that Schmeling had suffered serious injuries to his ankle and thumb and might never fight again. The Sharkey-Scott match, the newspapers argued, effectively had become a title bout. (Schmeling actually had a long career ahead of him, retiring from boxing in 1948.)[13]

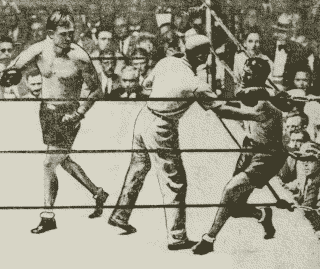

Phil Scott can't continue

As the boxers weighed in, reports generally said Sharkey was a five-to-one favorite. Some said the odds were closer to ten-to-one. Few believed Scott would last longer than three or four rounds in the scheduled fifteen-rounder.[14]

The contest attracted a number of celebrity attendees, in addition to the New York Mafiosi and their gambler associates. New York Yankee slugger Babe Ruth and his wife were noted. Former world heavyweight champion Gene Tunny and his wife sat ringside, in the company of National Geographic editor John Oliver La Gorce and his wife. The crowd also included Cincinnati Reds right fielder Harry Heilman; Bernard Gimbel, president of the Gimbels department store chain; Ford Motor Company President Edsel Ford and Robert Scripps of Scripps-Howard publications.[15]

As expected, the bout ended quickly. Sharkey used devastating body blows - some of which may have been below the beltline (a charge echoed in other Sharkey fights) - to exploit his opponent's lack of conditioning. Scott was knocked down three times. In the third round, when a Sharkey body punch left Scott hanging helplessly on the ropes, Scott told referee Lou Magnolia that he could not go on. The referee called the fight a technical knockout for Sharkey. [16]

By 1930, Lucania was a top aide to Masseria, close enough to pal around with "Joe the Boss" on an excursion like the Miami trip. It is uncertain when the relationship between the two men began. Lucania had also been close to other leading racketeers, including Arnold Rothstein and Jack "Legs" Diamond.[17]

Lucania had acquired the "ugly scar from his left ear to his collar" fairly recently - just about four months earlier. He was found beaten and bleeding along Hylan Boulevard near Prince's Bay, Staten Island, early in the day, October 17, 1929.

He told police that he had been abducted in Manhattan, thrown into a car, beaten, driven to Staten Island and dumped by the roadside. Lucania did not say who beat him, but authorities concluded it was underworld rivals.[18]

In covering that fall 1929 beating story, the Miami Daily News indicated that Lucania was already known in the south Florida area. It reported that he had been in Miami in the winter of 1928-29. Locals recalled Lucania in the company of visiting New York racketeers Arnold Rothstein and Thomas "Fatty" Walsh - both recently murdered. Though Walsh was killed in Miami in 1929 and his closeness to Lucania was common knowledge, the Dade County sheriff reportedly had no record of questioning Lucania in connection with that murder investigation.[19] Coverage of the February 1930 gambling raid looks to be the first time that Lucania was publicly linked with Mafia boss Masseria.

Masseria

Masseria appeared to be at the height of his underworld power. The underworld chief faced quiet opposition from some Sicilian-born underworld bosses and from factions that had been close to his late rival D'Aquila. Masseria made matters worse by welcoming Neapolitans into the Mafia criminal society.

Vito Genovese of New York and Al Capone of Chicago became lieutenants of his New York-based crime family. The appointment of Capone as a remote "capodecina" was offensive and perilous for the Joseph Aiello-commanded Mafia organization in Chicago, which had been competing with Capone for Prohibition Era racket territories in the Windy City.[20]

Masseria responded to opposition with brutality. When a conflict erupted between Bronx crime boss Gaetano Reina and Masseria lieutenant Ciro Terranova, Masseria ordered Reina killed. That order was carried out on February 26, 1930, as Masseria was on his way to Florida to attend the Sharkey-Scott fight.[21]

After a twelve-hour stay in county jail, the suspects were released on bail. According to the Miami Daily News, a California race horse owner secured their release by placing $5,200 in cash with the sheriff's office.

The News noted that the money seized in the raid was returned to the suspects as they left the jail.[22]

Seventeen of the gambling suspects were brought into court on March 6. They pleaded guilty to gambling and vagrancy. Dade County Judge W.F. Brown sentenced each to pay a $100 fine or serve thirty days in jail on the gambling count. He suspended sentences for vagrancy, providing the defendants immediately leave the city.[23]

Lucania and Masseria were tried separately in Miami Criminal Court the following day. Both men pleaded guilty to the charges against them. Lucania was fined $1,000, and Masseria was fined $800. Thirty-day jail sentences were suspended on the condition that they immediately leave the city.[24]

(Interestingly, press reports of the court proceedings referred to Lucania as "Luciano." No explanation for the change from "Lucania" was provided. Though Lucania seemed never to use that spelling himself, most writers since that time have preferred to refer to him as "Luciano.")

Shortly after their return to New York, Masseria's opponents openly rose against him in the Mafia's Castellammarese War. The war ended the following spring, with the Lucania-ordered assassination of Joe the Boss.[25]

1 -The date has been subject of some disagreement, with many printed reports pointing to the morning of March 1 for the arrests. Local news source Miami Daily News and the FBI state that the arrests occurred February 28.

2 -"Nab 19 B'way big shots in Miami raid," New York Sunday News, March 2, 1930, p. 2.

3 -Most press accounts failed to list nineteen names. The New York Times reached the total of nineteen by counting Frank Jacone, arrested later. The Times listed Joe Masseria and John Masseria separately. Other papers referred to Masseria as either Joe or John.

4 -"Nab 19 B'way big shots in Miami raid."

5 -"Charles Luciana, with aliases," FBI memorandum, file no. 39-2141-X, Aug. 28, 1935, p. 4; "Arrest 19 at Miami in gambling clean-up," New York Times, March 2, 1930, p. 33; "Miami hotel is raided today; officers find over $73,000; one man had roll of $60,000," Piqua OH Daily Call, March 1, 1930, p. 1; "Nab 19 B'way big shots in Miami raid." It seems likely that the Miami and Miami Beach addresses were merely seasonal.

6 -"Three slay man in street and flee," New York Times, Oct. 11, 1928, p. 20; Flynn, James P., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI Report no. 92-6054-324, NARA Record no. 124-10278-10231, July 1, 1963, p. 12.

7 -"Arrest 19 at Miami in gambling clean-up," New York Times, March 2, 1930, p. 33.

8 -"Nab 19 B'way big shots in Miami raid."

9 -"Miami hotel is raided today; officers find over $73,000; one man had roll of $60,000."

10 -"Capone slips away from new prison, eluding throngs, New York Times, March 18, 1930, p. 1; Hunt, Thomas, "Al Capoe's long stay in Philadelphia," Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement, October, 2010.

11 -"Ton of heavies replaces whale as attraction," Miami Daily News, Feb. 26, 1930, p. 13; "Boxing chiefs stand behind Magnolia edict," Miami Daily News, Feb. 28, 1930, p. 1.

12 -"Scott unconcerned about reports of his bad condition," Orlando FL Evening Star, Feb. 16, 1930, p. 4; "Phil Scott's condition," Fort Lauderdale FL News, Feb. 17, 1930, p. 4.

13 -"Sharkey-Scott fight will not be broadcast Feb. 27," Orlando FL Sentinel, Feb. 20, 1930, p. 8; Runyon, Damon, "Scott appears in good shape for big battle," Tampa Tribune, Feb. 23, 1930, p. 14; "Ton of heavies replaces whale as attraction," Miami Daily News, Feb. 26, 1930, p. 13; "Schmeling injury stamps fight of Sharkey and Scott Thursday as near championship affair," Miami Daily News, Feb. 26, 1930, p. 1.

14 -"Sharkey ready for his fight at 197 pounds," Miami Daily News, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 1; "Scott outweighs Sharkey 8 pounds," Tampa Times, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 1; "Ton of heavies replaces whale as attraction."

15 -Massengale, Maude Kimball, "Fair contingent attends fight in smart attire," Miami Daily News, Feb. 28, 1930, p. 12.

16 -"Boxing chiefs stand behind Magnolia edict," Miami Daily News, Feb. 28, 1930, p. 1; Brown, Ned, "Ned Brown tells how Sharkey won fight," Miami Daily News, Feb. 28, 1930, p. 20.

17 -"Nab 19 B'way big shots in Miami raid."

18 -"Ride victim found with throat cut," New York Daily News, Oct. 17, 1929, p. 4; "'Ride' victim wakes up on Staten Island," New York Times, Oct. 18, 1929; "Ride victim who escaped locked up to save life," New York Daily News, Oct. 18, 1929, p. 4; "Gangster 'taken for ride' lives to tell about it," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 17, 1929, p. 1.

19 -"'Lucky' Lucania is remembered in Miami," Miami Daily News, Oct. 18, 1929, p. 22; "Gables murder seen Rothstein mystery sequel," Miami Daily News, March 7, 1929, p. 1.

20 -Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 87-88.

21 -"Castellammarese War of La Cosa Nostra," FBI report 92-6054-551, NARA no. 124-10277-10302, Nov. 20, 1963, p. 1; "Wealthy ice dealer slain in doorway," New York Times, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 3; Jarrell, Sanford, "Police save rival from wife's fury," New York Daily News, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 2; "Baff murder of 1915 echoes in new death," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 3; "Third man slain in ice rate war," Asbury Park NJ Evening Press, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 4.

22 -"Gambling raid men obtain bond," Miami Daily News, March 1, 1930, p. 14.

23 -"17 Miami Beach gaming raid prisoners fined," Tampa Tribune, March 7, 1930, p. 14.

24 -"Charles Luciano and...," Miami Daily News, March 8, 1930, p. 13; "Lucania is called shallow parasite," New York Times, June 19, 1936; "Charles Luciana, with aliases," FBI memorandum, file no. 39-2141-X, Aug. 28, 1935, p. 4.

25 -"Castellammarese War of La Cosa Nostra," FBI report 92-6054-551, NARA no. 124-10277-10302, Nov. 20, 1963, p. 2; Flynn, James P., "La Cosa Nostra," FBI Report no. 92-6054-324, NARA Record no. 124-10278-10231, July 1, 1963, p. 14