In the early morning of September 29, 1960, twenty-five-year-old Joseph Crapisi, a city employee in Kansas City, Missouri, was just getting home after an evening out. [1] He parked his new Chevrolet Impala and began the short walk to his house at 528 Harrison Street, near East Missouri Avenue in the city's Italian North End.

Crapisi was nearing the front door of his building, when an armed man or men stepped out from the darkness and fired at him. Left slumped, bleeding at his doorstep was one of the Federal Bureau of Investigation's secret Mafia sources.

Kansas City Star

The FBI was caught flatfooted a few years earlier when state police in Apalachin, New York, broke up what turned out to be a board meeting of the country's leading Mafiosi. The FBI had never adequately investigated the Mafia before and was largely unaware of its membership and operations. So the Bureau had to play catch-up quickly when the Justice Department ordered it to tackle the Mafia.

To grow its knowledge of the Mafia, the FBI tried to persuade mobsters to share confidential information about the organization. Many mobsters refused to become government witnesses and testify against their colleagues in court but were willing to secretly feed the FBI Intel. The Intel obtained from informers (and listening devices) formed the basis of the FBI's initial understanding of the Mafia's membership, history, and rituals.

In many crime families, it took the FBI years to convince an inducted member to talk. In the meantime, federal agents relied on Intel from any individual with knowledge of the organization. In Kansas City, the FBI turned to Joseph Crapisi, the son of a former member, to help define the local Mafia crime family and its workings.

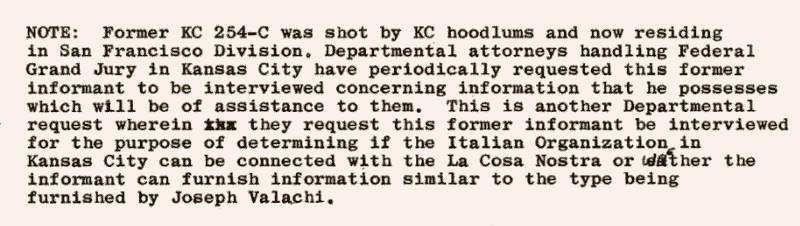

Joseph Crapisi

Joseph Lee Crapisi was born December 29, 1934, in Kansas City. [2] His parents were Sicilian immigrants, Salvatore and Lillie Crapisi. [3] There is very little public information about Crapisi's life before or after the shooting incident. He was arrested in 1954 for attempted rape (although the district attorney dropped the charges) and questioned in a robbery. [4] It's unclear if any of these incidents impacted the decision to talk.

In September 1959, Crapisi was hired as a commercial recreation inspector in Kansas City's welfare department, earning $295 per month. Inspectors, considered members of local law enforcement, maintained standards at amusement centers and issued fines for code violations. Crapisi inspected downtown pool halls, nightclubs, massage parlors and establishments with coin-operated gambling machines. [5]

City officials fired Crapisi from his job after the shooting. They pointed out that he should never have been hired in the first place since he had a criminal record, hid that fact on his employment application and performed poorly on a qualifying examination compared to other candidates. [6]

Crapisi told federal agents that he was "close" to Mafia leader Nicholas Civella because his father had been a "very close friend of 'The Men at the bakery.'" [7] The bakery was a reference to Roma Bakery in the city's Italian neighborhood.

Cousins Joseph Filardo and Joseph Cusumano, two influential Kansas City Crime Family leaders, operated the popular bakery. They were natives of Crapisi's father's hometown of Castelvetrano, Sicily, who settled in Kansas City near the start of the Prohibition Era. Crapisi added that Cusumano was his brother Jack's "godfather."

Joseph Crapisi advised that he "only had to report to [Civella]." The FBI didn't characterize Crapisi's relationship to Civella or the crime family in the available intelligence reports, but an outsider generally did not have direct access to a Mafia boss.

Charles Crapisi

Salvatore "Charles" Crapisi was born May 10, 1889, in Castelvetrano, Sicily, about fifty miles southwest of Palermo. [8] Charles and his entire family, including his parents Giacomo and Caterina, immigrated to the United States. The family crossed the Atlantic in stages, with forty-seven-year-old Giacomo reaching the U.S. first in 1907 and Caterina arriving last in 1915. [9]Charles's immigration date is unclear, but he was living in the United States by 1914. [10] [11] [12]

The Crapisi family settled in Russellville, Alabama, near the Tennessee border, likely working in the region's mining sector. They relocated to the Midwest, attracted by plentiful jobs in the mining, railway, and manufacturing sectors. Charles and two brothers worked as quarrymen at a mining company in Moline, Kansas, east of Wichita and about 180 miles southwest of Kansas City. [13] The brothers all served in the United States military during the First World War.

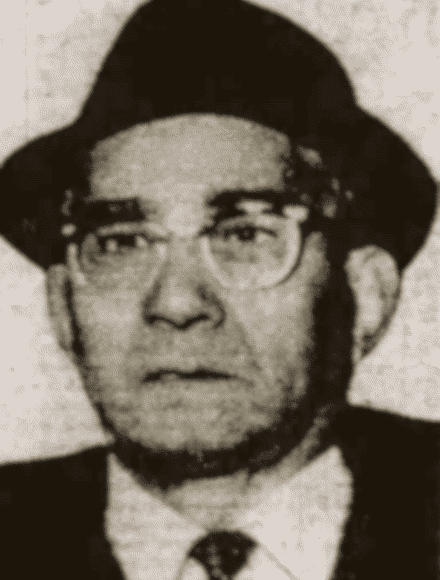

Angelo Donnici

After the war, Charles Crapisi moved to Kansas City and settled on 534 Forest Street in the city's Italian North End. [14] The house was a few doors from the home of Anthony Mangiaracina, whose brother John and nephew Joseph Gurera were prominent Kansas City Crime Family members. [15] Crapisi's other known associates, Joseph Olivio, Angelo Donnici, and Angelo Nigro, were early Mafia members in Kansas City.

Charles Crapisi and Anthony Mangiaracina became partners in a major drug smuggling ring. [16] The ring sold heroin throughout the Midwest during the 1930s. Olivio and Donnici, saloon owners in Kansas City's Italian North End enclave, headed up the local wholesale network. Crapisi was reportedly Donnici's lieutenant and operated his own restaurant as a cover for his criminal activities. Harry J. Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, called Crapisi "a very important dealer." [17] It's unclear how long Crapisi was involved in the distribution of heroin, but it could have been decades. Authorities arrested his brother Frank in 1923 for possessing and dealing fifty grams of morphine. [18]

Joseph Olivio

The ring's heroin came originally from the Chinese port city of Tientsin, then under Japanese control. [19] Smugglers smuggled it through Egypt's Suez Canal to Paris, France, and then to New York City. Finally, the heroin was delivered to Kansas City, which acted as a central distribution hub. Crapisi and his partners then distributed it to areas around the country, including Seattle, New Orleans, Denver and Houston.

After a nineteen-month investigation, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics broke up the drug ring in 1939 and charged Crapisi, Anthony Mangiaracina, Angelo Donnici, Joseph Olivio and other codefendants with narcotics violations. According to federal prosecutors, the network moved $12 million worth of heroin annually.

Rather than fight the charges, Charles Crapisi pleaded guilty to the charges. He was sentenced to a $3,000 fine and a five-year prison term at the federal penitentiary in Texarkana, Texas. [20] His codefendants also received lengthy prison sentences. Crapisi served a little over a year of his sentence before dying unexpectedly on December 31, 1940, of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was fifty-one. [21] Joseph Crapisi was six years old when his father died.

After law enforcement arrested Charles Crapisi for narcotics trafficking, they raided his home at 528 Harrison Street. Behind the house, they found a massive underground cellar accessed through a secret door. Measuring four feet wide, seven feet high, and twenty feet long, it stored 300 gallons of illegal alcohol in 5-gallon cans. [40]

Joseph Crapisi secretly shared information with federal agents as early as February 1958. [22] The FBI confirmed his cooperation in an intelligence report, stating Crapisi was "active as an informant concerning matters in the criminal intelligence field." Though FBI typically redacts informants' names before permitting public release of its documents, Crapisi's name was not redacted. His informant symbol code was "KC 254."

FBI memorandum

Crapisi code number revealed

Crapisi was not the first Mafia member's son to provide information to the Bureau. In 1955, federal agents in Pennsylvania persuaded Joseph LaTorre, son of former Pittston Crime Family boss Steven LaTorre, to share confidential information. [23] Like Crapisi, Joseph LaTorre was not a Mafia member.

Available FBI intelligence reports don't reveal Crapisi's motivation for speaking with agents.

The FBI's approach to questioning Mafia informers shifted fundamentally in the post-Joseph Valachi era, and the new approach was reflected in what Crapisi revealed. After Valachi's revelations, federal agents became more curious about the organization and its hierarchy, membership and rituals. They inquired about induction ceremonies, dates, sponsors and ranks in a way they didn't earlier. Interviews conducted with Crapisi before Valachi flipped focused primarily on individuals rather than the organization or the individual's relationship to the organization.

Nicholas Civella

Joseph Crapisi told federal agents that Kansas City's Italian criminal organization was called the "the Clique," "the Boys" or "the Syndicate." He said the day-to-day boss of the organization was Nicholas Civella: "All communications and directions to the membership went through Civella." [24] However, in Crapisi's view, the real bosses were his father's old chums, Joseph Cusumano and Joseph Filardo, who operated the Roma Bakery. If a problem arose that required "a higher decision," Civella took it up with "the men at the bakery."

Cusumano and Filardo had controlled the organization for as long as Crapisi could remember. The membership never dealt directly with Cusumano and Filardo. The only individual who brought matters to them was Civella. Crapisi called Civella, "the Man." He said Johnny Lazia, Charles Carollo, Charles Binaggio and Tony Gizzo previously occupied the position of "the Man."

Crapisi was present when Civella golfed with mobster John Vitale from St. Louis. He was also around on several occasions when Civella met with Anthony Accardo from Chicago. Civella didn't introduce them, but Crapisi learned Accardo was "'the Man' from Chicago." Crapisi told federal agents that he never asked questions about the organization because members told you only what they wanted you to know.

The Kansas City underworld power structure described by Crapisi was similar to the arrangement in Chicago. Sam Giancana was the acknowledged Outfit boss and had broad freedom to operate, but he reportedly consulted with Paul Ricca and Anthony Accardo on the most significant decisions.

Joseph Crapisi admitted he wasn't a Clique member and wasn't aware of its rituals and rules. However, Crapisi told federal agents that he was "well acquainted with the members and activities" of the organization. He shared that information despite having been instructed never to identify anyone as belonging to the Clique. [25]

An individual needed to be sponsored by a "godfather" to become a member. Everyone in the organization grew up together in the city's North End. Members frequently married into each other's families, which helped them form close relationships. As a result, the organization was united and didn't have factions. No member referred to the organization as the "Family."

Joseph Cusumano

Crapisi described an organizational hierarchy similar to other crime families though he didn't use the same terminology popularized by Joseph Valachi. For example, Civella had an echelon of men reporting to him who handled gambling, labor, etc. Each of these men commanded a group of followers. Valachi would have referred to a group as a "regime," but Crapisi stated that "no special name [was] given to this group of men."

Before an individual in the organization committed a crime, it had to be approved by his superior. If an individual committed a robbery without his leader's approval, he could be required to return the stolen loot. If he ignored a superior's specific instructions, the organization might kill him.

Crapisi said much of Valachi's underworld terminology was unfamiliar to him. For example, he told federal agents that he had never heard members use terms like "our friend," "button men," or "soldier." In addition, Crapisi never referred to a "consigliere," or a similar position. (It is possible that Filardo or Cusumano held such a position, and Crapisi misunderstood their underworld status. Rather than ultimate bosses, they may have been Civella's advisory council. )

Crapisi was unsure if the Clique and Cosa Nostra were the same organization. The first time he heard the term "Cosa Nostra," was when Valachi used it publicly. However, Crapisi was confident that the Clique would help Cosa Nostra members if asked. He said the only interaction between the Clique and other Mafia crime groups that he witnessed were the meetings with Anthony Accardo and John Vitale.

His lack of familiarity with terminology popularized by Valachi, which the FBI adopted and applied to every Italian crime family in the country, demonstrated that the organization was, in fact, primarily a nameless entity. Whether members called it "Mafia," "Clique" or "Cosa Nostra," it was all the same. The FBI was still learning in 1963 that Italian crime groups employed different euphemisms to describe similar things depending on the time and place.

Joseph Filardo

Intelligence reports indicated federal agents interviewed Joseph Crapisi several times in Binghamton, New York, in April 1958. [26] The FBI office in Binghamton was its closest to Apalachin, New York, where dozens of underworld leaders were found meeting just five months earlier. Binghamton itself had been the scene of a similar meeting, largely unnoticed by law enforcement, in 1956. At the time of the Crapisi interviews, a number of Apalachin attendees were being called back to the region to be questioned by a grand jury. It's unclear if Crapisi was in the area at the direction of the FBI, in support of the Clique or for some other reason.

Crapisi confirmed to federal agents that Nicholas Civella and Joseph Filardo both attended the November 14, 1957, Apalachin meeting. However, Crapisi made the strange claim that, after talking with "Italians," he concluded that most individuals summoned to the gathering had no advance notice of its purpose. Crapisi didn't specify his sources or elaborate on their conversations. He further claimed that most people he spoke to thought the gathering was related to the October 25, 1957, murder of Gambino Crime Family boss Albert Anastasia.

However, according to Crapisi, one objective of the meeting was for the bosses "who are getting up in years" to introduce their successors to other bosses. He indicated that was the reason Filardo brought Civella to the meeting. (Crapisi speculated that Carl De Luna would eventually succeed Civella.)

Hospital room guarded

The noise of the shotgun blasts at three o'clock in the morning of September 29, 1960, awakened neighbors, and they alerted authorities. Police found the wounded Crapisi trying to get into his home. An ambulance rushed him to the hospital. Doctors determined a shotgun pellet entered his neck and exited through his right cheek. Additional pellets were found embedded in a building at the corner of Harrison and Missouri, where the shooting occurred. There was a lot of blood, but Crapisi wasn't gravely wounded. He recovered in the hospital for two weeks, his room guarded by two police officers. [27]

Police interviewed Crapisi, but he was uncooperative. Crapisi said he had no enemies, and there was no reason to target him. Police speculated the shooting was a warning since the assailant fired from a distance of 40 feet, making it a difficult shot. [28] However, pointing a loaded shotgun at someone's head and pulling the trigger usually demonstrates deadly intent.

The available FBI intelligence reports don't reveal who targeted Crapisi or why. They only indicated that Crapisi was shot by "KC hoodlums."

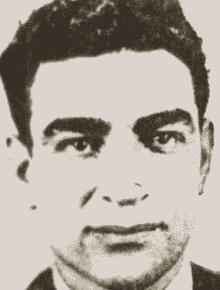

Local police questioned Kansas City Mafia member Felix Ferina. [29] At the time, Ferina was awaiting trial for alleging shooting a government witness in a narcotics trial. [30] They also questioned Mafia members John Cardarella, Sam Palma, Carl De Luna, Charles Cacioppo, and Thomas Simone. [31]

Felix Ferina

The mobsters stated they had known Crapisi for years but knew of no reason why he should be a target. Simone admitted talking to Crapisi at a restaurant owned by Palma shortly before the shooting but denied any involvement. [32] Authorities never charged anyone in the shooting.

Given Crapisi's connection to the Mafia leadership, through his father's relationship with Cusumano and Filardo, it seems unlikely anyone in the local Mafia would have taken action against Crapisi without the bosses' approval.

The organization could have discovered Crapisi was an informer, but that's unlikely since the FBI is careful to protect the anonymity of informers. The press never reported that he was suspected of cooperating.

However, a partially redacted FBI intelligence report indicated Crapisi gave testimony "periodically" before a grand jury. It is not clear if the testimony occurred before or after his shooting, and the target of the grand jury investigation remains uncertain. [33] Possibly this grand jury testimony, not Crapisi's FBI cooperation, somehow came to the attention of the Clique and led to his shooting.

Whatever troubles Crapisi had, they did not end with the September 1960 incident. Ordinarily, when the Mafia fails to kill a suspected snitch, that's the end of it. The violent message either convinces the survivor to clam up or it pushes him into the arms of law enforcement. No further action is taken. But this case was different.

Joseph Crapisi's cousin was hoodlum Anthony Trombino. A former Midwest gangster, Trombino moved to California in the late 1940s and with partner Anthony Brancato became active in the Los Angeles underworld. Mobster Jimmy Fratianno murdered Trombino and Brancato in 1951.

After becoming an informant, Fratianno revealed that the deaths of the "two Tonys" were ordered because they had been robbing and extorting individuals protected by the Los Angeles Crime Family.

On March 23, 1961, six months after the shooting of Joseph Crapisi, two armed assailants ambushed his older brother. Shotguns were fired at Jack Crapisi outside his Kansas City home, 520 North Lawndale Avenue. [34] Jack suffered pellet wounds to the back, face and chest. The wounds were not severe, and he was sitting up and talking when the ambulance arrived to take him to the hospital. A witness heard Jack say, "Oh God, I'll lose my job now." [35]

Jack Crapisi and his wife await an ambulance

Like his brother, Jack refused to cooperate. A police spokesman said, "it was very apparent he was withholding information that would help us, and the information he gave us was of little value." [36]

Local police linked the incident to his brother's shooting. The county prosecutor remarked that "there are signs of an organized situation in these attempted spot killings." [37] Police found all four doors of Crapisi's vehicle opened when they arrived at the scene, suggesting he had passengers on the night of the shooting.

Although Jack had been arrested in the past for armed robbery, he wasn't a known gangster. He worked as a truck driver for a painting company.

Police presumed Joseph Crapisi was the primary target, and the assailants shot Jack because they could not reach his brother. Jack answered questions before a grand jury investigating the shooting. However, he continued to live openly in Kansas City without further incident. There is no evidence Jack cooperated with the FBI. And police never arrested anyone for the shooting.

It is worth noting that Civella and Filardo were under pressure at the time and may have been highly motivated to locate and discipline anyone who suspected of supplying information to FBI.

The shootings raise questions about the gunmen. For example, was their failure to kill the brothers a sign that the shootings were intended as warnings, as police speculated in Joseph's case, or was it an indication the triggermen were incompetent?

Joseph Crapisi dropped out of sight after the shootings. Newspaper speculation that whoever was after Crapisi might have finished the job was downplayed by the Kansas City police department, suggesting the authorities were in touch with him.

Vincent Infusino came to the United States in 1912. He initially settled in St. Louis before coming to California in 1940. Infusino operated a tavern before becoming a peach farmer. [41]

Crapisi left Missouri and moved to California. [38] In 1963, the FBI reinterviewed him about the Kansas City underworld in light of Valachi's revelations about Cosa Nostra. It was then that Crapisi provided the bulk of his information about the organization he called the Clique.

In 1967, Crapisi reached out to federal agents one last time to pass on Intel about the Mafia in the San Francisco area. By then, Crapisi's value to the FBI was negligible. The Bureau had developed member sources in Kansas City and San Francisco better positioned to provide Intel.

Nonetheless, Crapisi advised that San Francisco Crime Family member Vincent Infusino visited San Francisco to meet with James Lanza and Bill Sciortino – the boss and underboss of the San Francisco Crime Family. [39] Infusino lived about ninety miles east of San Francisco in the city of Modesto. Infusino also met with Anthony Scavuzzo, a San Jose Crime Family member. However, Crapisi didn't know what they discussed.

The intelligence report is vague about how Crapisi came about this information, but it suggests he met with Infusino. The Sicilian-born Infusino was a former member of the St. Louis Crime Family before transferring membership to the San Francisco Crime Family and may have been an old friend of Crapisi's family.

When the FBI was only beginning to understand Italian organized crime properly and was still largely unaware of Kansas City's Mafia membership and structure, Joseph Crapisi provided some of the first answers.

With Crapisi's cooperation, federal agents slowly built their knowledge of the organization, which wielded power in the Midwest and across the United States through its influence in Las Vegas casinos and national unions.

However, the full scope of what Crapisi told investigators and the reason for his apparent falling out with the organization will remain unknown until his complete FBI informant file is released. Nevertheless, Crapisi may well be remembered as Kansas City's most important Mafia informer until Joseph Gurera flipped ten years later.

1 "A City Inspector Shot In The Neck," Kansas City Star, Sept. 29, 1960.

2 Joseph Lee Crapisi, Missouri Birth Registers, Dec. 29, 1934; Joseph Lee Crapisi and Beverly Jean Kimberling Marriage License, Jackson County, Missouri, No. B83802, Jan. 11, 1960.

3 United States Census of 1940, Missouri, Jackson County, Kansas City, Ward 1, Enumeration District 116-2.

4 "Critical Of A Hiring," Kansas City Times, Oct. 1, 1960.

5 "A City Inspector Shot In The Neck," Kansas City Star, Sept. 29, 1960.

6 "Sealed Lips Still Veil Shooting," Kansas City Star, Dec. 21, 1960.

7 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, San Francisco Office, Oct. 23, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10212-10402.

8 United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, FamilySearch.org.

9 New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924, FamilySearch.org.

10 New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924, FamilySearch.org. The only "Salvatore Crapisi" to immigrate that resembles the description came over from Corleone, Sicily, in 1914.

11 Louisiana, New Orleans Index to Passenger Lists, 1853-1952, FamilySearch.com.

12 New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924, FamilySearch.org. Charles' brother Joseph immigrated in May 1909, joining his family in Russellville.

13 New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924, FamilySearch.org. By 1915, Giacomo Crapisi was living at 511 Harrison Street, Kansas City.

14 United States, Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940, FamilySearch.org.

15 Edmond Valin, "'Joey G' drops a dime and body or two," Rat Trap, November 2019.

16 "33 Named In Probe Of Dope Ring," Moberly-Monitor Index, April 19, 1939.

17 "G-Men Break Up Coast-To-Coast Narcotic Ring," Bradenton Herald, April 12, 1939.

18 "Grand Jury Is Discharged," Kansas City Star, May 11, 1923.

19 "Murder Started Drug Ring Hunt," Springfield Leader and Press, April 13, 1939.

20 "Charles Crapisi Is Dead," Kansas City Star, Jan. 1, 1941.

21 Texas Deaths, 1890-1976, FamilySearch.org.

22 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, San Francisco Office, Oct. 11, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10215-10301.

23 Edmond Valin, "In Pittston, informing runs in the family," Rat Trap, June 2020.

24 FBI, "Meeting of Hoodlums, Apalachin, New York," Albany Office, Aug. 28, 1959, NARA Record No. 124-10290-10329, p. 31.

25 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Kansas City Office, Dec. 17, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10289.

26 FBI, "Meeting of Hoodlums, Apalachin, New York," Albany Office, July 8, 1958, NARA Record No. 124-90103-10092, p. 153.

27 "Victim Of Shotgun Guarded By Police," Kansas City Times, Sept. 30, 1960.

28 "Sealed Lips Still Veil Shooting," Kansas City Star, Dec. 21, 1960.

29 "Victim Of Shotgun Guarded By Police," Kansas City Times, Sept. 30, 1960.

30 "Felix Ferina Is Acquitted," Atchison Daily Globe, Dec. 18, 1960.

31 "Sees A Jury Probe In Crapisi Shooting," Kansas City Star, March 24, 1961.

32 "Sealed Lips Still Veil Shooting," Kansas City Star, Dec. 21, 1960.

33 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, San Francisco Office, Oct. 11, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10215-10301.

34 "Gun Blasts Wounds A Man," Kansas City Times, March 24, 1961.

35 "Shooting Victim Is A Mystery Figure," Kansas City Star, March 28, 1961.

36 "Police In Talk With Crapisi," Kansas City Times, March 27, 1961.

37 "Sees A Jury Probe In Crapisi Shooting," Kansas City Star, March 24, 1961.

38 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, San Francisco Office, Oct. 11, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10215-10301.

39 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Sacramento Office, Aug. 20, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10122. The FBI described Crapisi as "closely allied with members of the San Francisco Crime Family."

40 "In Liquor Also," Kansas City Star, April 13, 1939.

41 "Modestan, 77, Denies Links With Mafia," Modesto Bee, Jan. 15, 1970.