Editor's note: The following article originally appeared in the April 2013 issue of Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement. It was initially revised for this website in January 2018, and it was updated in February 2022.

Police remove Alfredo Santantonio's body from a Brooklyn flower shop.

Santantonio

On July 11, 1963, two men wearing makeup disguises to hide their identities entered the Flowers By Charm flower store at 197 Avenue T in Brooklyn, New York. They approached the store owner behind the counter and fired five bullets into him before fleeing. Left lying dead on the floor was forty-year-old Gambino Crime Family member Alfredo Santantonio. [1]

The murder had the hallmarks of a professional killing. The shooters stole nothing, and Santantonio’s father-in-law, who was in the store, was left unhurt. Police ruled out any connection to the Gallo-Profaci War, then raging in Brooklyn between different factions of the organization headed by Joseph Profaci. However, it didn’t take investigators long to figure out that it was a mob hit.

Nearly eighteen months earlier, authorities sentenced Santantonio to eight years in prison for selling stolen bonds. [2] He was appealing his conviction when he was gunned down. Colombo Crime Family member Gregory Scarpa, who had begun secretly cooperating with the Federal Bureau of Investigation the year before, advised that “it was common talk in Brooklyn that [Santantonio] was killed because he was cooperating with the Government.” [3]

Scarpa confided that Mafia bosses intended to use Santantonio’s murder to undermine informant Joseph Valachi’s upcoming appearance before a U.S. Senate committee investigating organized crime. [4] The government, according to Scarpa, “was planning to back up Valachi’s testimony with testimony from Santantonio.” By killing Santantonio, bosses hoped the government “would not be able to use Valachi now because we got rid of their corroborator.”

The FBI never publicly confirmed Santantonio’s cooperation even though newspapers reported that the Mafia likely killed him for “cooperating with investigations into narcotics and counterfeiting activities on the East Coast." [5]

However, recently declassified FBI intelligence reports confirmed that between December 1962 and July 1963, Santantonio secretly furnished valuable Intel under the informant symbol code “NY 3864”.

Alfredo Santantonio was born on March 13, 1923, in Brooklyn, New York. He was named for his maternal grandfather, Alfredo Calderone. Santantonio’s parents, Philip and Rosa, were Italian immigrants. Philip was a stenographer, and Rosa was a presser in a textile factory.

Santantonio grew up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Nicknamed “Freddie the Sidge,” he completed his education at Edward B. Shallow Junior High School in the eighth grade. Santantonio served two terms in the United States Navy, 1943 to 1947 and 1947 to 1949, before being honorably discharged. He married Marie Colombo in 1954.

After leaving the Navy, Santantonio was arrested in February 1950 at LaGuardia Airport in Queens, New York, and charged with illegal possession of heroin worth $336,000. [6] Authorities alleged that Santantonio and an associate delivered heroin and other drugs to contacts throughout the southern United States, including New Orleans. His criminal record also included arrests for assault and robbery in Florida.

His surname appears variously as “San Antonio,” “Sanantonio,” and “Santantonio” in census records and newspaper reports. Santantonio spelled and signed his surname as “Santantonio” when he registered for military service during World War II. His grave marker also used the spelling “Santantonio.”

Parisi

Alfredo Santantonio told federal agents that he was inducted into the Gambino Crime Family in 1953 in the presence of boss Albert Anastasia. [7] His sponsor was his brother-in-law Joseph Parisi. [8] Fifty-seven-year-old Parisi married thirty-eight-year-old Marie Santantonio in 1953. Born and raised in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Parisi was secretary-treasurer of Teamsters Local 27, which controlled the city's waste management industry.

Parisi had a criminal record dating to 1921 with eleven arrests. He served two and a half years in prison following a conviction for rape. In 1934, he was arrested with mob bosses Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Louis Buchalter for organizing an illegal cartel in New York’s paper box industry. Parisi was a prime suspect in the murder of union rival John Acropolis in 1952. [9]

Parisi enriched the coffers of the Gambino Crime Family by creating a cartel in New York City’s private waste management industry and charging customers exorbitant fees. He enforced control through violence and threats of strikes against uncooperative businesses. He reported directly to Anastasia.

Anastasia assigned newly inducted Santantonio to caporegime Charles Dongarra. The Sicilian-born Dongarra controlled a large crew that included Joseph N. Gallo, who would one day become the crime family’s consigliere. Anastasia took a “liking” to Santantonio and gave him the responsibility to oversee a craps game. It allowed him to see Anastasia every day. Santantonio was in the process of establishing a close relationship with Anastasia when the boss was murdered in 1957.

Adelstein

In 1956, Joseph Parisi died of a heart attack at age sixty. Anastasia was convinced that Parisi’s union associate, Bernard Adelstein, withheld $40,000 collected by Parisi before his death from shaking down private waste management companies. Anastasia intended to use the money to bribe politicians to make new laws to force businesses to use mob-controlled companies.

Anastasia ordered Santantonio to collect the money. Santantonio assaulted Adelstein twice, but he refused to admit he stole the money. Anastasia called off another beating after law enforcement began investigating the waste management industry, and things got “too hot.”

Santantonio said Gambino Crime Family members paid regular dues between $10 to $25, depending on their income level. Sometimes they had to pay a “special assessment” if a member was in trouble. Individuals were too fearful ever to question how the bosses spent the money.

Crew leader Charles Dongarra spent his summers at a farm in Windham, New York. While he was away, Joseph N. Gallo acted in his place. Gallo had many contacts in Baltimore and Philadelphia and often visited on business. [10]

Dongarra

According to Santantonio, Gambino Crime Family member Anthony Scotto replaced Anthony "Tough Tony" Anastasio, Albert’s younger brother, as boss of the Brooklyn waterfront. [11]

Gambino Crime Family members living in Miami reported to Joseph Silesi, one of approximately two-dozen caporegimes in the crime family. [12] Thomas Altamura acted in his place when he was away.

Santantonio said the organization recently suspended Miami-based member Joseph Indelicato because of excessive indebtedness. Indelicato had to report daily to Altamura until he repaid his debt and could get reinstated. [13]

Santantonio cleared up the mysterious disappearance of former Gambino Crime Family caporegime Tommy Rava. Rava, Carlo Gambino’s chief rival to replace Anastasia as boss of the crime family, attended the underworld conclave in Apalachin, New York, in 1957, before dropping out of sight. Rava was presumed murdered, but his body was never found.

According to Santantonio, Joseph Indelicato and Thomas Altamura murdered Rava at a funeral parlor in Florida. They put Rava in a body bag, stuck him numerous times with an icepick and dumped his body in the ocean. [14]

Indelicato and Altamura also murdered a swindler named Louis “Babe” Silvers at the Blue Bay motel in Miami. Silvers was allegedly murdered on the orders of Gambino Crime Family member Carmine Lombardozzi after he stole money from the organization. Santantonio said Indelicato and Altamura got away with the Silvers murder after allegedly paying the district attorney a $40,000 bribe.

Alfredo Santantonio fed the FBI Intel about mobsters outside the Gambino Crime Family.

Bonanno Crime Family member Benjamin Valvo told Santantonio that Frank Garofalo, a narcotics trafficker, used to be the underboss of the crime family. Valvo said that Garofalo “got frightened” and fled to Italy when Vito Genovese and Carmine Galante received lengthy prison sentences for dealing heroin.

Valvo said his brother Matteo Valvo replaced Giovanni Tartamella as a caporegime after Tartamella suffered a stroke. Salvatore Bonanno, the son of crime boss Joseph Bonanno, was elected to the position of consigliere, also formerly held by Tartamella. Santantonio said John Morales was the “acting boss” when Joseph Bonanno was absent from New York City. [15]

Valachi

Santantonio said the ultimate decision-making body in the Mafia underworld was called the “High Commission.” Santantonio said it’s called the “High Commission” to distinguish it from dispute-resolving commissions in each crime family. Cleveland's John Scalish was allegedly a member of the “High Commission” as early as 1955. Philadelphia’s Angelo Bruno joined in 1962. Gerry Catena represented the Genovese Crime Family while boss Vito Genovese was incarcerated. [16]

According to Santantonio, Dongarra updated his crew every few years about the new policy decisions made at the national level. For example, in December 1962, Dongarra advised that Carlo Gambino passed on word the “High Commission” had strictly forbidden members from participating in bombings, kidnappings and narcotics distribution.

Santantonio said the bombing prohibition was in light of the recent car bomb in Cleveland that killed mobster Charles Cavallaro and his son. The narcotics ban had been in place for years due to pressure from law enforcement.

Santantonio identified hundreds of Mafia members in New York City's five crime families, some of them for the first time. [17] And he helped to ensure the existing FBI membership lists were accurate. For example, until he pointed it out, the FBI had Santantonio listed as a member of the Colombo Crime Family. [18]

Alfredo Santantonio gave a breakdown of the actions necessary to become an inducted member of the Gambino Crime Family. The FBI was still in the dark about much of this stuff in early 1963. Joseph Valachi and other informants were only beginning to fill in the blanks about the Mafia’s inner workings.

Santantonio said the organization's purpose was “self protection and self preservation from the underworld itself.” He said individuals who operated on the fringes of the law, like bookmakers, needed to be affiliated with the organization to avoid being robbed or assaulted. He said the organization took a percentage of the profits for this service. [19] He said virtually all bookmakers in New York City were Mafia members or had the backing of one. [20] He advised that New York City had about two thousand Mafia members. [21]

Members of the organization weren’t required to engage in illegal activity, but given their criminal backgrounds, most members did. [22]

According to Santantonio, if an individual wanted to join the organization, his sponsor would perform a background check on him, contact friends and relatives in the neighborhood and Italy, check with sources in the police department and talk to other crime families. An existing member could sponsor a relative into the organization without a background check. An individual would be disqualified for membership if he was a pimp or if his wife was a prostitute. Family leaders liked to induct “good earners” because they meant more money in the leader’s pockets.

To test if an individual was worthy of membership, the organization might ask him to participate in a killing - what Santantonio called “dirty work.” If the individual was with a member and he happened to kill someone because of some unexpected trouble, he would be inducted into the crime family immediately. Or, if he didn’t perform well, the organization would kill him.

If the background check panned out, the sponsor would seek his caporegime’s permission to induct him.

Induction ceremonies usually occurred within a month of the sponsor extending the invitation to the individual. Because the organization was so “vicious,” individuals always accepted for fear of being killed if they refused. The induction ceremony could occur in the basement of a member’s home when his family is away or on some remote farm. [23]

The boss, underboss and consigliere attend each Gambino Crime Family induction ceremony. The caporegime conducts the ceremony, not the boss. All members of the caporegime’s crew are present. The meeting begins with the members standing and holding hands. Then, in Italian, the caporegime says, “In the name of our ‘Causa,' the meeting is open.”

The caporegime starts by reminding members late with their assessments to pay up before moving on to agenda items. At the end of the meeting, the caporegime announces that the crime family intends to induct a new member. Finally, he gives the name of the proposed member and his sponsor.

If an existing member furnishes credible proof of why a proposed member should not be inducted, the organization will kill the proposed member on the spot. Hearsay allegations are not accepted. According to Santantonio’s experience, a member will sometimes throw out some bogus accusation to make the sponsor look bad in front of the boss. If there are no objections, members stand up, hold hands again, and the caporegime will close the meeting.

At this point, the caporegime will bring the proposed member into the room and ask him if he knows why he is there. The proposed member will state that his sponsor invited him to join the crime family. The caporegime then asks if he knows anything else about the organization. The proposed member will say “no,” as his sponsor has coached him.

The caporegime will break down the membership rules for the new member, including paying the assessment, clearing all legal and illegal activities, and avoiding selling narcotics or using bombs. According to Santantonio, Gambino Crime Family members are not required to put the organization before their religious faith or country like other families.

After the proposed member agrees to all the terms, everyone stands, the members hold hands, and the induction ceremony begins.

The sponsor will prick his finger and the finger of the proposed member with a needle. Then they touch their two bloodied fingers together. Next, the sponsor places a burning picture of a saint in the proposed member's hands and gets him to repeat the following oath, “I swear that I will not reveal anything that was said here, and I will do anything that I am told to do.”

The sponsor kisses the new member and introduces him to his caporegime with the words, “amigo nostra” or “he is a new friend of ours.” Next, the caporegime provides the new member with information about the leaders of the other crime families and the Commission members. The meeting ends when everyone stands, holds hands, and the caporegime announces in Italian, “the meeting is closed.” Members leave the meeting location in groups of two to avoid raising suspicion.

Santantonio said in 1963 that the books were closed, preventing the induction of new members, and would remain closed until the bosses decided that they needed money. He said the “act of ‘making’ individuals is a business proposition.”

According to Santantonio, the Gambino Crime Family had between seven hundred and one thousand members. The Genovese Family had about five hundred members. The Lucchese and Bonanno Crime Families had about two hundred members. The Colombos were the smallest at a hundred and fifty members. [24]

Costello

Three shootings rocked the New York underworld in 1957. The shootings were connected, although that was not clear to the FBI until a few years later when member-informants like Joseph Valachi and Santantonio talked.

On May 2, 1957, Frank Costello, the Genovese Crime Family boss, was shot and wounded when Vincent Gigante surprised him entering his Central Park apartment. Gigante was charged with attempted murder, although a jury acquitted him at trial. Santantonio advised federal agents that Thomas Eboli and Dominick Alongi were with Gigante the night of the shooting. However, witnesses never identified them, and they were never charged. Valachi provided similar Intel.

On June 17, 1957, two gunmen shot Albert Anastasia's underboss Frank Scalise as he shopped at a vegetable market in the Bronx. Authorities never solved the murder, but Santantonio told federal agents that Anastasia ordered Scalise's murder for complaining to Frank Costello about Anastasia's alleged involvement in narcotics trafficking. By the late 1950s, the Commission prohibited members from dealing narcotics because of the fear of lengthy prison sentences.

Scalise accused Anastasia of forcing drug dealers to make him a secret partner in their transactions. Scalise's murder, according to Santantonio, had nothing to do with selling Mafia memberships as Valachi claimed in debriefings with federal agents but for exposing Anastasia's illicit drug dealing.

Santantonio cleared up the mystery of who shot Albert Anastasia on October 25, 1957. Santantonio's understanding of how the murder happened is probably close to the truth since he learned the details firsthand from one of the alleged conspirators. [25]

Santantonio advised that Anastasia's murder was orchestrated by three underlings named Joseph Riccobono, Joseph Biondo and Charles Dongarra. All three were Sicilian-born caporegimes active on Manhattan's Lower East Side. They received a tip from another caporegime named Joseph Franco that Anastasia intended to kill them. [26] However, Santantonio never explained why Anastasia targeted them. [27]

Anastasia

Rather than wait for Anastasia to take them out, Riccobono's group struck first while Anastasia was having a shave and haircut in a Manhattan hotel barbershop. Santantonio said the killers knew he frequented the location, making it ideal.

Dongarra told Santantonio that the actual shooters were Gambino Crime Family member Stephen “Stevie Coogan” Grammauta and his associate, Joseph Cahill. [28] Grammauta was a convicted heroin dealer in the crew of his cousin Steve Armone. Joseph N. Gallo and Andrew Alberti were also part of the murder conspiracy.

The shooters hid the murder weapons in the hotel room of boxer Johnny Russo, the nephew of Gambino Crime Family member John “Johnny Connecticut” Russo. After the shooting, Grammauta and Cahill took the subway home.

Santantonio said Commission members never learned the identities of the two individuals who pulled the trigger. In the absence of other information, underworld rumors flourished that Larry and Joey Gallo or Carmine Persico were responsible. [29]

After the murder, Riccobono reached out to Gambino Crime Family caporegime Domenico Arcuri to declare that he represented the group that killed Anastasia. He requested that Arcuri notify the other caporegimes in the crime family about what happened. Riccobono also contacted New York bosses Thomas Lucchese and Vito Genovese. [30]

According to Santantonio, Riccobono appeared before an underworld “trial” at the estate of Genovese Crime Family caporegime Richard Boiardo in New Jersey. Representatives from New York's five crime families were there, including Carmine Galante, Thomas Lucchese, Vito Genovese, Tommy Rava, Johnny Robilotto, and Joseph Biondo. [31]

Riccobono, speaking on behalf of the group, took full responsibility for the murder. According to Santantonio, Riccobono spoke eloquently and persuaded the bosses that the group acted in self-defense. As a result, the bosses issued pardons to everyone involved, including Grammauta and Cahill.

According to Santantonio, mob leaders convened the Apalachin meeting three weeks later, on November 14, 1957, to notify other crime bosses not in attendance at the New Jersey meeting about the reasons behind Anastasia's murder. [32]

Santantonio implied Vito Genovese had reason to support a strike against Albert Anastasia. Frank Costello and Anastasia were close allies. Santantonio claimed that after Genovese sent Vincent Gigante to shoot Frank Costello, Costello retaliated by providing Anastasia with a $250,000 war chest to gather an army to kill Genovese. [33]

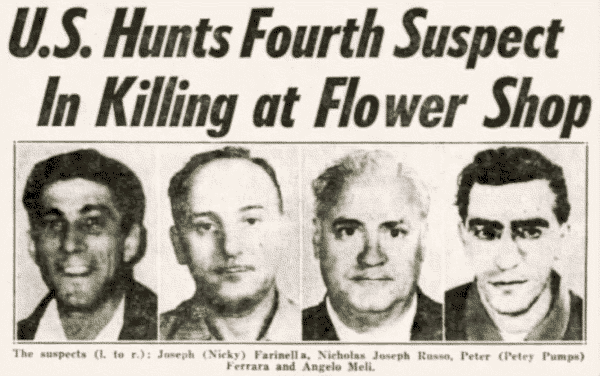

Suspects in the killing of Santantonio

The valuable Intel furnished by Santantonio abruptly ended after eight months when he was shot dead. [34] Authorities determined an execution squad led by Brooklyn-based caporegime Peter Ferrara killed Santantonio. As part of an unrelated investigation, law enforcement planted a listening device in a mob-controlled Coney Island service station. The bug unexpectedly recorded Ferrara discussing details of the murder conspiracy.

Ferrara suspected Santantonio revealed details about the organization’s heroin trafficking network to law enforcement. As a result, family leaders, including Paul Castellano, ordered Ferrara to kill Santantonio to silence him and serve as a warning to others to keep quiet. The shooters were allegedly Angelo Meli and Joseph Farinella, while Ferrara and Nicholas Russo acted as backups and waited outside the flower store in getaway vehicles. [35]

Mafia member Meli was a convicted heroin dealer. Meli’s father, Giosue, and brother, Philip, were also identified as Gambino members. Russo and Farinella were Trenton, New Jersey-based members. [36] Informer Salvatore Gravano implicated Russo and Farinella in two murder conspiracies in the 1980s.

Authorities arrested Ferrara, Meli, Farinella and Russo after the shooting. However, the district attorney tossed the murder charges in 1967 after the United States Supreme Court banned using evidence obtained from illegal electronic surveillance. [37]

Santantonio, a Navy veteran, was buried at the Long Island National Cemetery in East Farmingdale, New York.

Around the time Alfredo Santantonio was killed, another Gambino Crime Family member faced his own life and death struggles in Brooklyn. Carmine Lombardozzi was a caporegime with one of the largest crews in the crime family. He replaced the deceased Joseph Franco in 1957.

Lombardozzi

Lombardozzi made a fortune in gambling, loan sharking, labor racketeering and selling stolen securities. He was at the forefront of white-collar crime long before it became the hallmark under the future boss, Paul Castellano. Lombardozzi was one of five Gambino Crime Family members to attend the mob meeting at Apalachin in November 1957. But two missteps nearly cost him his life.

His first mistake was an ill-advised romance with the daughter of crew member Sabato Muro. Lombardozzi was a married man, and it was against the organization’s rules to keep a relative of another member as a mistress. As a result, Muro brought a formal complaint against him. To save himself, Lombardozzi divorced his wife and married Muro's daughter.

Lombardozzi found himself in hot water again when his brother and nephews attacked a federal agent conducting surveillance at his father’s funeral. The assault led to increased federal scrutiny of the Gambino Crime Family and further soured the low-key Carlo Gambino on him. [38]

Lombardozzi's superiors demoted him to soldier and replaced him with Joseph Gennaro. Many in the underworld suspected he would wind up dead. [39]

Despite these incidents, Carmine Lombardozzi continued to prosper in the criminal underworld and lived to age seventy-nine, dying of natural causes in 1992. Gambino Crime Family leaders attended his wake.

On August 22, 1968, authorities charged Carmine Lombardozzi with violating federal laws for fraud and transporting stolen goods. Soon afterward, an informant thought to be Lombardozzi began to share confidential information with the FBI. [40] The informant, assigned the symbol code “NY 6436,” identified Mafia members and provided valuable historical information.

Lombardozzi and the informant match on four key points:

Intel furnished by “NY 6436” is included in FBI intelligence reports produced between 1968 and 1969. He may have cooperated beyond then, but publicly available reports citing “NY 6436” are confined to that period.

“NY 6436” estimated that New York City had two thousand Mafia members, but five hundred were dead. [49] He said there is no official retirement process in the Mafia. However, members usually retired in their mid-seventies when the organization stopped calling on them to perform a service for the crime family. A member must abide by all the organization rules until he dies. The organization does not provide retired members with a pension.

The informant said the Commission had forbidden members from engaging in narcotics or counterfeiting since 1953. The penalty was death.

Father and sons, or brothers, can belong to different crime families as long as they have permission from the bosses'.

“NY 6436” told federal agents that Pittsburgh boss John LaRocca and Raymond Patriarca from the New England Crime Family attended the Apalachin meeting but escaped undetected by law enforcement. [50]

He said Russell Bufalino headed his own fifty-member crime family based in Pittston, Pennsylvania. [51] Members lived in the small towns near Pittston and were active in the garment industry. The informant said he met Bufalino at Apalachin and had lunch with him often when he came to New York City. He described Bufalino’s underboss as an “old time greaseball.” “NY 6436” dispelled misinformation supplied by Philadelphia Crime Family member-informant Rocco Scafidi that claimed Bufalino was a Lucchese Crime Family member.

The Gambino Crime Family informant told federal agents that Chicago Outfit leader Sam Giancana was part-owner of Capra’s restaurant in Miami. He said Tampa boss Santo Trafficante was there “almost every night.” [52]

Rava

He stated that Tommy Rava and Neil Dellacroce killed former Gambino Crime Family member Johnny Robilotto after he decided to back Carlo Gambino to head the crime family. He said Robilotto had initially supported Rava to succeed Albert Anastasia but changed his mind. According to “NY 6436,” Robilotto was popular, and other crime families still talked about the murder.

He told the FBI that Genovese Crime Family member Salvatore Granello was investigating the murder of his son and threatening to kill those responsible. Michael Granello was killed gangland-style in December 1968 after ignoring warnings about stepping on the toes of Mafia members. (Salvatore Granello was murdered a short time later.) [53]

The informant told federal agents about Tampa Crime Family member Lennie (last name unknown), who had been slated for death by boss Santo Trafficante. Trafficante farmed out the contract to the Genovese Crime Family because Lennie had moved to Coney Island, Brooklyn. The first attempt to kill Lennie was unsuccessful. The contract passed to the Lucchese Crime Family, who also “missed.” Eventually, the Gambino Crime Family got in on the act, but Lennie got wind of what was going on and fled to San Francisco. The informant said that Lennie was still living there as far he knew. [54]

Like Alfredo Santantonio, informant “NY 6436” told federal agents about a pre-Apalachin meeting at the estate of Richard Boiardo. The gathering, larger than Apalachin, was an “inquiry” into the killing of Albert Anastasia. Attendees included Commission members Joseph Bonanno and Vito Genovese from New York, Sam Giancana from Chicago, Steve Magaddino from Buffalo, Joseph Ida from Philadelphia, and Joseph Zerilli from Detroit. According to the informant, the Commission members were “feeling the pulse” everyone there. He said he got the impression some of the bosses knew beforehand why Anastasia was killed, but others were in the dark. The meeting ran all day until the following morning at five o'clock. [55]

Carlo Gambino spoke at the meeting, justifying Anastasia’s murder because “he was using people from other ‘families’ to kill people, and he was killing some people should not have been killed.” [56] “NY 6436” didn’t disclose the results of the “inquiry,” only that “it was decided to continue [the] meeting at another location.” [57] This second gathering turned out to be Apalachin.

Although “NY 6436” claimed he attended both meetings, Santantonio’s account of the pre-Apalachin meeting that followed Anastasia’s murder appears to be more accurate. “NY 6436” advised that the meeting at Richard Boiardo’s estate occurred “two months prior to the Apalachin meeting” and “was to discuss the Anastasia killing,” which is impossible since Anastasia died less than three weeks before Apalachin. [58]

Even if “NY 6436” mixed up the dates, it's hard to imagine bosses from Philadelphia, Buffalo, Detroit and Chicago traveling to New Jersey for a meeting and then proceeding to Upstate New York in the short window between Anastasia’s murder and the Apalachin conclave. (Santantonio made no mention of Commission members outside of New York attending the pre-Apalachin meeting.)

In his recollection of events from ten years earlier, “NY 6436” although an eyewitness, may have conflated details from three separate meetings that occurred in 1957: 1. The reconciliation meeting between Vito Genovese and Albert Anastasia after the Costello shooting in May; 2. The pre-Apalachin meeting (or underworld trial) after Anastasia's assassination; 3. The Apalachin conclave in November.

Joseph Bonanno provided a glimpse of the first of the three meetings. According to his autobiography, after the Costello shooting, he and the other New York bosses attended a dinner where Anastasia and Genovese kissed and hashed out a (temporary) truce. [59] Additional evidence of this meeting came from a secret FBI listening device, which intercepted a conversation between Philadelphia mob leaders about a gathering in the “last quarter of 1957” including Albert Anastasia, Sam Giancana, Anthony Accardo, Dominic Pollina and others. [60]

Meeting details are scant, but Anastasia acted “fearful” and wouldn’t go to the originally proposed venue at the estate of Richard Boiardo. As a result, mob leaders moved it to the basement of a restaurant.

The meeting that “NY 6436” said occurred “two months prior to the Apalachin meeting” may have been the reconciliation dinner between Anastasia and Genovese that ultimately failed. And contrary to what he told the FBI, the pre-Apalachin meeting that followed Anastasia’s murder probably was as Santantonio described it - an underworld trial of Anastasia’s killers conducted strictly by the New York bosses.

How long “NY 6436” cooperated is unknown. But it appears his cooperation was short-lived, and his information had little lasting impact. Special agent Bruce Mouw took charge of the FBI's investigation of the Gambino Crime Family in 1980. Mouw commented that he found the Intel furnished by informants “was ancient history, at least a decade old” and was like “starting with zero.” [61]

1 “Ex-convict is slain by 2 in flower shop,” New York Times, July 12, 1963; New York and Brooklyn Daily, July 12, 1963. “When reporters asked [Santantonio’s father-in-law] to tell his story he turned away icily and said, ‘I don’t know nothing.’”

2 “Three sentenced in U.S. bond fraud,” New York Times, Feb. 6, 1962. A jury convicted Santantonio, Edward Coppola and Anthony Campisi of “fraudulently passing $50,000 worth of stolen United States Savings Bonds.” In addition, three others involved in the scheme received suspended sentences after pleading guilty and cooperating with the government.

3 FBI Memorandum, New York Office, August 5, 1963.

4 FBI Memorandum, Sept. 4, 1963, Letter from the SAC, New York Office to the Director, FBI, p. 6.

5 “Ex-convict is slain by 2 in flower shop,” New York Times, July 12, 1963.

6 “Foil delivery of $336,000 in dope on plane,” New York Daily News, Feb. 1, 1950.

7 FBI, Criminal Intelligence Program, New York Office, Jan. 3, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90066-10007, pp. 2-11. Santantonio stated that Anastasia held the rank of underboss at the time of his induction. The induction date or Anastasia’s position is off, since Anastasia was underboss between 1931 and 1951 and boss between 1951 and 1957.

8 Santantonio entered the Navy at twenty years old and left at twenty-six in 1949. Parisi's influence may have been decisive in getting Santantonio inducted since he was involved in the criminal underworld only a short time.

9 “Expect crime elite at Parisi funeral,” Newsday, Sept. 18, 1956.

10 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, July 10, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10278-10253.

11 FBI, Crime Conditions in the New York Division, New York Office, Nov. 27, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10348-10069, p. 26.

12 FBI, Crime Conditions in Miami Beach, Florida, Miami Office, March 19, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90031-10015, p. 59.

13 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 49.

14 FBI, Crime Conditions in Miami Beach, Florida, Miami Office, March 19, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90031-10015, p. 59.; FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Sept. 26, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10290-10437, p. 254. A Bonanno Crime Family informant told federal agents that Toddo Avarello shot Rava to death.

15 FBI, Crime Conditions in the New York Division, New York Office, Nov. 27, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10348-10069, p. 7.

16 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 15.

17 FBI, Criminal Intelligence Program, New York Office, Aug. 16, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10212-10393, pp. 18-28.

18 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, June 1, 1963, NARA Record Number 124-10278-10231, p. 68.

19 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 9.

20 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 32.

21 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 16.

22 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 17.

23 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90149-10084, p. 25.

24 FBI, La Causa Nostra, New York Office, Jan. 31, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10211-10300, p. 54.

25 Peter Maas, The Valachi Papers, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968, pp. 248-249. According to Valachi, bosses Vito Genovese and Thomas Lucchese orchestrated Anastasia’s murder. They feared Anastasia, a strong supporter of Genovese rival Frank Costello, may have wanted to avenge Costello’s shooting. Both versions may be accurate: Riccobono and his group went after Anastasia because he intended to kill them, and Lucchese and Genovese took advantage of the opportunity to remove Anastasia when it presented itself.

26 Franco died before Commission members could test the veracity of his accusation.

27 An aspect of Anastasia’s murder was the tension between the primarily non-Sicilian faction that supported the Calabrian-born Anastasia and the Sicilians coalescing around Frank Scalise, Joseph Riccobono, Joseph Biondo and Carlo Gambino.

28 Mob reporter Jerry Capeci broke the story in 2001. Capeci claimed the shooters were Stephen Grammauta and his associate Arnold Wittenberg (rather than Joseph Cahill).

29 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Feb. 12, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10003, p.12. Killers from outside the Gambino Crime Family were always unlikely since use of outside gunmen was one rationale put forward by the anti-Anastasia faction to justify the murder.

30 FBI, Criminal Intelligence Program, New York Office, Jan. 3, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-90066-10007, pp. 8-10. Vito Genovese and Thomas Lucchese were likely aware of the assassination plot in advance, although not necessarily behind it. As a result, the outcome of the underworld trial may have been predetermined.

31 The only New York City crime family without a representative was the Colombo Crime Family. Joseph Bonanno, who wrote a candid memoir about his life in organized crime, didn’t mention this meeting.

32 The Valachi Papers, pp. 251-252. According to Valachi, the Apalachin agenda items were: formal recognition of Genovese as new Family boss, expulsion of unworthy members, and prohibition of drug dealing.

33 FBI, NY 3864, New York Office, Jan. 14, 1963, 92-1450-25.

34 U.S. Congress, Senate, Invasions of Privacy: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 89th Congress, 1st Session., pp. 3, 1158. In 1965, U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach revealed that twenty-five federal organized crime informants were murdered between 1961 and 1965.

35 “U.S. hunts fourth suspect in killing at flower shop,” New York Daily News, March 28, 1965.

36 Farinella was likely inducted in the 1970s.

37 “Three to go free in killing because of ban on bugging,” New York Daily News, Sept. 4, 1967.

38 FBI, Criminal Intelligence Program, C.A. Evans to Mr. Belmont, April 30, 1963, NARA Record No. 124-10284-10234.

39 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10308, p. 73; FBI, Memorandum, New York Office, April 25, 1963, pp. 4-5. Gregory Scarpa told federal agents that many mobsters believed Gambino would order Lombardozzi’s death “in order to get the FBI to remove the pressure from Brooklyn.”

40 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Sept. 26, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10290-10437, p. 244; FBI, LCN Conspiracy, New York Office, Feb. 11, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10290-10499, p. 2.

41 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Oct. 30, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10244, p. 2. Considering Lombardozzi’s age and rank, he was likely inducted sometime after WWII.

42 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Feb. 12, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10002. “Informant advised that he drove to the meeting with several members of the Gambino group from Brooklyn.”

43 FBI, NY 6436-C-TE TECIP, New York Office, Oct. 29, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10244, p. 3.

44 Lombardozzi was the junior member of this group and may have attended as an aide-de-camp or chauffeur. He may have been there to corroborate (the late) Joseph Franco’s claim that Anastasia was plotting to kill Riccobono.

45 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Oct. 30, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10240, p. 2.

46 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, New York Office, Oct. 20, 1967, NARA Record No. 124-10277-10308, p. 168; FBI, NY 6436-C-TE TECIP, New York Office, Oct. 29, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10244.

47 FBI, NY 6436-C-TE TECIP, New York Office, Oct. 29, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10244, p. 2. Agents often produced multiple reports on the same subject. A comparison can often lead to a fuller understanding of the subject and provide inadvertent clues to an informant’s identity.

48 FBI, NY 6436-C-TE TECIP, New York Office, Oct. 29, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10244, p. 2. “Informant was introduced to Bufalino at Appalachia (sic)...”

49 FBI, LCN Conspiracy, New York Office, Feb. 11, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10290-10499, p. 2.

50 FBI, NY 6436-C-TE TECIP, New York Office, Oct. 29, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10244.

51 FBI, La Cosa Nostra, Nov. 25, 1968, NARA Record No. 124-10293-10248.

52 FBI, Santo Trafficante, Jr., Miami Office, Feb. 26, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10213-10207, p. 33.

53 FBI, Salvatore Granello, New York Office, Jan. 3, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-90066-10074.

54 FBI, Santo Trafficante, Jr., Miami Office, Feb. 28, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10213-10206, p. 13.

55 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Feb. 12, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10002. “Informant advised that he drove to the meeting with several members of the Gambino group from Brooklyn. They drove to a big restaurant in Newark, New Jersey, which informant advised he believed was owned by Jerry Catena. They parked their automobile in the parking lot of this restaurant where they were met by ‘made guys’ from New Jersey who had their own automobiles. They got out of their car, as did other, and the Jersey ‘made guys’ acted as chauffeurs and drove them to Richie Boiardo’s house two at a time.”

56 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Feb. 12, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10003, p. 12.

57 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Feb. 12, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10003, p. 13.

58 FBI, LCN, New York Office, Feb. 12, 1969, NARA Record No. 124-10297-10003, p. 12.

59 Joseph Bonanno with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York Simon & Schuster, 1983, p. 185.

60 FBI, Angelo Bruno, Philadelphia Office, June 22, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10203-10430, pp. 10-13; FBI The Criminal Commission, New York Office, Dec. 27, 1962, NARA Record No. 124-10288-10164, p. 32. In 1962, Philadelphia Crime Family member Pasquale Massi attended a meeting in New Jersey involving Anastasia and other Commission members. It can be dated to “last quarter of 1957” because: Dominic Pollina had succeeded Joseph Ida as Philadelphia boss, Sam Giancana had succeeded Tony Accardo as boss of Chicago (Accardo could have been introducing Giancana to the other Commission members on this trip), and Anastasia was acting “fearful,” which would be consistent with the loss of his mob protector, Frank Costello.

61 Howard Blum, Gangland, New York: Simon&Schuster, 1993, pp. 43-48.