Note: An earlier Lucchese biography, written in 2007, was replaced with this article in 2022.

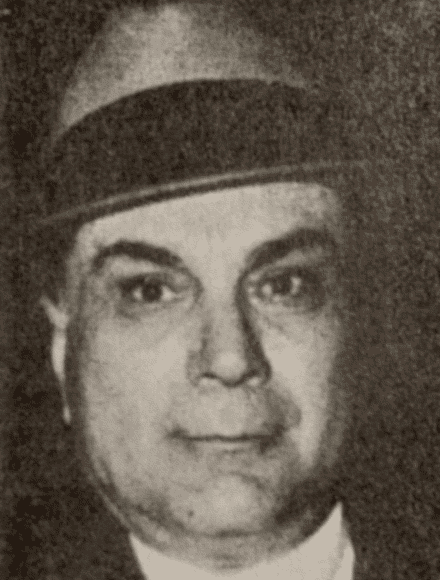

An East Harlem, New York, street gangster early in his life, Gaetano "Thomas" Lucchese used a flair for business, a knack for cultivating useful friendships and a talent for timely betrayal in his climb to the leadership of a New York-area crime family.

His Mafia organization, generally thought to be the second-smallest of the city's traditional five families, [1] often punched above its weight, due to boss Lucchese's extensive network of underworld and overworld connections. The level of influence he attained could not have been imagined in his early years.

Lucchese

Lucchese was born in Palermo, Sicily, the son of Baldassare, a barber, and Francesca Cinquemani Lucchese. His birthdate is commonly given as December 1, 1899 - that is the date he reported on his U.S. naturalization petition, and it agrees with his stated age of twelve upon his 1911 arrival in the U.S. A significantly earlier date is contained in transcribed (possibly transcribed incorrectly) birth records of the Brancaccio neighborhood in the southeast of Palermo. Those records indicate that Gaetano Lucchese was born December 2, 1895, about ten months after the marriage of his parents. [2]

The family of Baldassare and Francesca Lucchese included six children - three girls, three boys - by the time it crossed the Atlantic. Gaetano was the second-oldest child and oldest son. His siblings were sisters Pietra, Rosalia and Concetta, and brothers Antonino and Giuseppe.

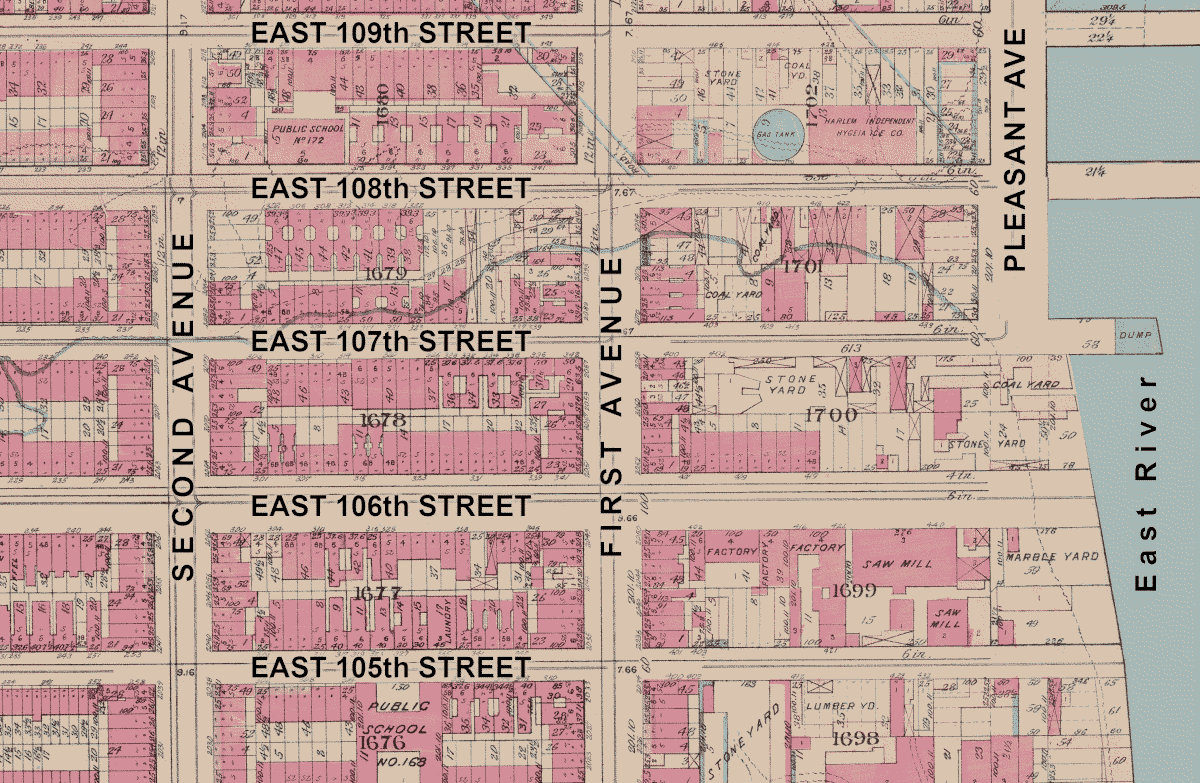

The family departed Italy from Naples on November 8, 1911, reportedly leaving no relatives behind in the Old Country. They sailed aboard the S.S. Duca D'Aosta. After a crossing of two weeks' duration, they reached New York on November 22, intending to meet Baldassare's brother-in-law Antonino Calli, at 237 East 106th Street, between Second and Third avenues. Their travel ordeal was extended when Francesca and at least two of the children were detained. The cause of the detention was listed as "husband," though Baldassare made the trip with his family and was evidently one of those detained.

They were discharged on the twenty-seventh, apparently into the care of Antonino Calli, then reported to be an "uncle" and to be living at 2042 First Avenue, between 105th and 106th streets (a couple of blocks from the previously noted address). Difficulty locating Calli may have been the cause of the detention. The family reunited just a few days before the November 30 national "day of Thanksgiving and prayer." [3]

East Harlem in 1911

The Luccheses settled into an apartment at 332 East 106th Street. Their new East Harlem neighborhood was an awkward combination of residential, commercial and industrial uses. Its residents were generally Sicilian immigrants. The neighborhood featured multi-story apartment buildings, many with ground-level retail stores, several public schools (P.S. 168, P.S. 172 and P.S. 121) and St. Lucy's Roman Catholic Church, as well as factories, a sawmill, a lumberyard, stoneworks and stoneyards. [4]

The area was home to a number of street gangs. Most noteworthy among these was the organization known as the 107th Street Mob, in which Gaetano Lucchese became active. It was likely in this period, that Lucchese first came into contact with Frank Costello. About nine years older than Lucchese, the Calabrian native Costello was a senior member of the East Harlem gang and was beginning to move into racketeering. Some years later, the gang was overseen by Mafia big shot Ciro "the Artichoke King" Terranova and his underworld colleagues.

As a teen and young adult, Joe Valachi, who later became famous as a Mafia informant, joined the "boys from 107th Street" in a number of criminal activities. Valachi later documented the influence of Sicilian, Irish and Jewish racketeers on the street gang and a late-1920s break between Irish and Jewish gangs (likely an early stage of what became the Schultz-Coll War) that pulled allied Sicilian and Italian gangsters in different directions. [5]

Brooklyn Times, March 28, 1922.

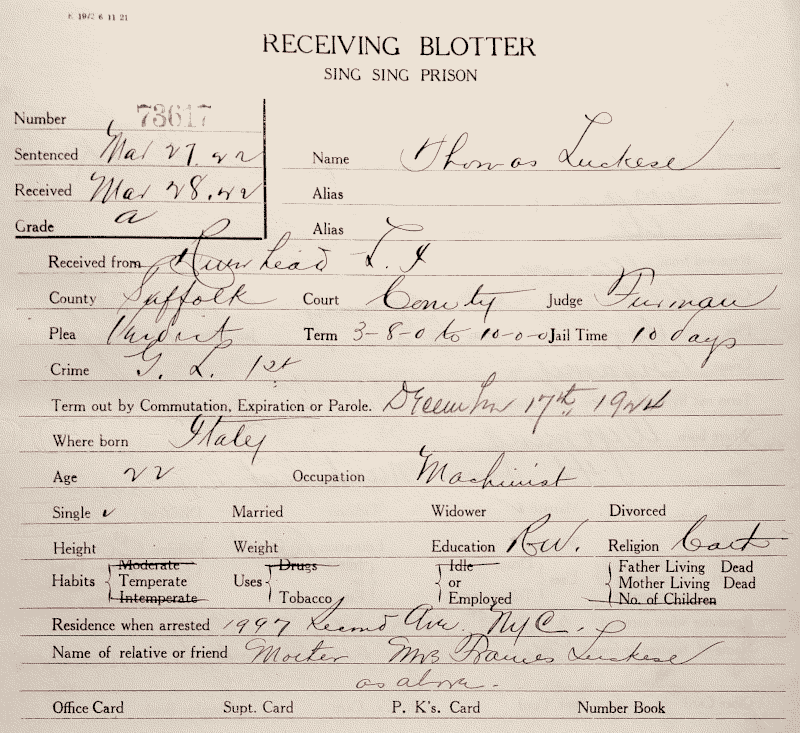

By the time of the 1920 U.S. Census, the Lucchese family had moved three blocks south to 1997 Second Avenue, near East 103th Street. For the census, "Thomas" Lucchese reported that he worked as a mechanic. Work with industrial machinery in an ammunition plant had already cost him his right index finger. [6] Though a bit more distant from the gang's stomping ground, he continued running around with the East 107th Street gangsters.

Thomas Lucchese (at the time using "Luckese" as the spelling of his surname) and friend Jack Spina, twenty-three, were arrested in Manhattan in early October 1921 while sitting in a recently stolen Packard Twin Six touring car. The automobile, valued at $3,000, had been reported stolen September 15 by flour broker William T. Harding, who left it parked in front of a theater in Bay Shore on Long Island. [7]

Mordecai Brown

During fingerprinting, one of the arresting officers noted Lucchese's missing finger and remarked that he was processing another "Three-Finger Brown." The name was a reference to former Major League Baseball pitcher Mordecai "Three-Finger" Brown, who excelled at his sport despite losing parts of two fingers on his throwing hand. As the story got around, Lucchese found himself with a nickname he reportedly disliked. (Years later, Lucchese told the New York State Crime Commission that he would "spit in the face" of anyone who dared call him "Three-Finger Brown.") [8]

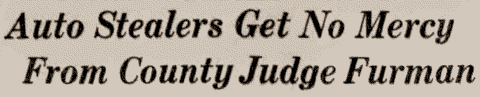

Lucchese and Spina were arraigned before Suffolk County Judge George H. Furman on October 21 on a charge of first degree larceny. They pleaded not guilty. Furman set bail at $5,000 each. [9]

A grand jury indicted both men in mid-February of 1922, and they went to trial in Judge Furman's Riverhead, Long Island, courtroom in the middle of the following month. At trial, the defense presented testimony and documents suggesting that Spina believed he legally purchased the Packard touring car from a man named J. Kellen and then sold the car to Lucchese. Kellen could not be located, and Spina recalled very little about him. The prosecution brought in handwriting experts who asserted that the sale documents attributed to the mysterious Kellen actually had been written by Lucchese. [10]

A jury deliberated for three hours on March 16 before finding Lucchese and Spina guilty of first degree larceny. Sentencing occurred on Monday, March 27.

Judge Furman at sentencing commented, "I want to give notice to the whole world that they cannot steal automobiles in Suffolk County and get away without being punished." Furman then imposed a heavy penalty, sentencing both men to serve between a minimum of three years and eight months and a maximum of ten years in prison. [11]

Lucchese and Spina served two years and nine months of their sentences before being paroled in mid-December 1924. [12]

Sing Sing Prison register

Following his release, Thomas Lucchese returned to his parents' home, still at 1997 Second Avenue in East Harlem. Living there with parents Baldassare and Francesca were brothers Antonino (Anthony), twenty-two and working as a plasterer, and Giuseppe (Joseph), fifteen and in school; New York-born brother James, eleven; and sister Rosalia (Rose), nineteen and working for a milliner. Thomas Lucchese went to work as a mechanic and avoided the appearance of criminal activity. On August 31, 1927, he was discharged from parole. [13]

Though the Board of Parole was convinced Lucchese was keeping on the straight and narrow, his prison term - the only one he would ever serve in his life - increased his underworld stature. He was regarded as a leader of the gang at 107th Street, and likely began working alongside area Mafiosi and corrupt local politicians in the rackets. [14]

Just one day before his discharge from parole, he was arrested for receiving stolen property. Perhaps evidence of his new connections, he managed to have the arrest filed under the name of "Thomas Arra." The charge was momentarily forgotten and did not impact the parole board's decision. [15]

Rosato

Lucchese married on September 25, 1927, taking Concetta (also known as Catherine) Vassallo, New York-born daughter of immigrants Fortunato and Angela Vadala Vassalo, as his bride. The ceremony reportedly occurred in Corona, Queens. A son was born to the couple in early July of the following year. As the oldest male child, he was given the name of his paternal grandfather, according to Sicilian tradition. [16]

Within two weeks of the child's birth, Thomas Lucchese and his pal Joseph "Joe Palisades" Rosato, also a Palermo-born mobster, were arrested for shooting to death Louis Cerasuolo. For this arrest, Lucchese's surname was written, "Lucase." Cerasuolo's wife and daughter, who initially identified Lucchese and Rosato as the killers, later reconsidered their position. When asked to identify the men in court, they were unsure. Lucchese and Rosato were freed. [17]

Lucchese became a resident of Queens, New York, by the time of the 1930 Census. He, his wife and their son, rented a place at 3238 Ninety-seventh Street. For the census, Lucchese reported that he was a manager but was apparent unsure of what sort of company he was managing. An early answer of "window cleaning" was crossed out and replaced by "plumbing." [18]

It would probably have been more accurate for Lucchese to describe himself as a racketeer (and some have speculated that the window cleaning job was actually a form of protection racket), as that appears to have occupied much of his time in that period. By 1930, conflicts in East Harlem forced gangsters to take sides. Lucchese separated from the Terranova- and Schultz-influenced organization, which had branches in East Harlem, the Bronx and Newark, New Jersey, and sided with Bronx-based Mafia leader Gaetano Reina and his lieutenant Tommaso Gagliano, who were quietly supportive of Schultz's enemies.

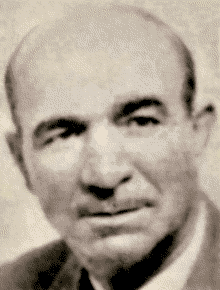

Reina was a native of Corleone, Sicily, who entered the U.S. as a minor in the early 1900s. He grew up in the rackets of East Harlem and appears to have established his own Mafia organization by the mid-1920s. Soon after that, Reina moved his family, including wife Angelina and their nine children, from East Harlem into a new, spacious home at 3183 Rochambeau Avenue in the Bronx.

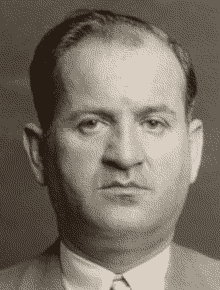

Reina

(Vargas/

Findagrave)

Reina, by then a wealthy ice dealer, reportedly spent little of his time at the Rochambeau Avenue home, preferring to live with a girlfriend, widow Mrs. Maria Ennis, on the Bronx's Grand Concourse. In the autumn of 1929, Reina (posing as Mr. James Ennis) and Mrs. Ennis moved to an apartment in a recently opened apartment building complex at 1511-1521 Sheridan Avenue, one block east of the Grand Concourse. [19]

The friction in the area underworld turned into a shooting war in this period. From mid-1928 on, evolving sets of allies and adversaries fought to gain control of bootlegging rackets in and around the city, as well as to avenge past wrongs. By the final months of 1929, the conflict pitted Dutch Schultz, his gang and his Terranova Mafia allies against Schultz's former associates, Peter and Vincent Coll, their gang (Valachi called them "the Irish mob" and "the Irish boys") and anti-Terranova mafiosi affiliated with the Reina organization. [20]

As the Colls and allies splintered off from Schultz, their gang, possibly with the support of Reina, may have been responsible for the humiliating holdup of Schultz's underworld and political allies at a December 8, 1929, Tammany Hall event at the Roman Gardens restaurant, 2401 Southern Boulevard, in the Bronx. [21] The dinner robbers were never identified, but Terranova seemed to know who they were. And police later discovered a calming note to Terranova ally John "Zacci" Savino that had been sent by someone with initials "M.C." Perhaps not coincidentally, Michael Coppola was a rising mafioso in the Bronx and Manhattan at the time, and he had connections with the Terranova organization and the Coll gang. [22]

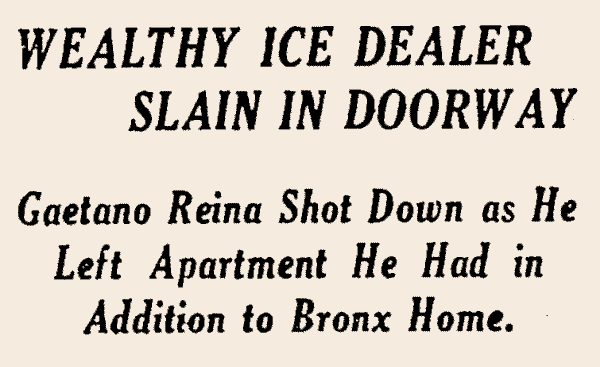

On Wednesday night, February 26, 1930, Gaetano Reina was helping Maria Ennis into his automobile in front of 1521 Sheridan Avenue, when a sawed-off shotgun erupted nearby and slugs ripped through his body. The shooter tossed his weapon aside and fled. Reina fell into the street. Ennis, unharmed by the flying lead, dropped to her knees beside him and cried out, "He's dying!" Reina was rushed to Morrisania Hospital but quickly succumbed to his wounds. [23]

Newspapers speculated that Reina had been murdered because of involvement in the murder of poultry merchant Barnet Baff years earlier or because of an ongoing conflict among rival ice dealers. [24]

NY Times, Feb. 27, 1930.

Joseph Bonanno, in his autobiography, suggested that Reina was killed because he had sided with mafioso Salvatore Maranzano in a struggle against the Mafia's reigning supreme arbiter, "boss of bosses" Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria. Bonanno's argument in favor of this view involved events and revelations incorrectly ordered in time. With the chronology corrected, no evidence remains for any Reina-Maranzano alliance against Joe the Boss. (The Maranzano-led opposition to Masseria reportedly formed after the murder of Gaspare Milazzo in Detroit, which occurred several months after Reina was killed. Bonanno switched the chronology so Milazzo appeared to have been killed before Reina.)

One other Bonanno suggestion was far more credible: He stated that Reina's secret opposition to Masseria was communicated to Giuseppe Morello - former leader of Corleone mafiosi in New York and a former Mafia boss of bosses - and that Morello reported it to Masseria. Reina and Morello were known to have strong business, underworld and old country connections, and Morello became a top aide in the Masseria's Mafia administration. [25]

An ice racket rivalry with Masseria has been widely accepted as the cause of Reina's murder. But it seems at least as likely that Reina participation in the recent violent schism in the East Harlem and Bronx underworld had become known to the Manhattan-based Mafia boss of bosses, who was a close Terranova ally.

One factor influencing the time and place of the attack on Reina may have been Reina's bad luck in selecting a love nest in the same apartment complex where Dutch Schultz's right-hand man lived. Records from the 1930s show that Schultz aide Abe "Bo" Weinberg resided at 1511 Sheridan Avenue in the Bronx. [26]

With Reina eliminated, Masseria installed Bonaventura "Joe" Pinzolo as the new boss of the Bronx-based Mafia organization. Pinzolo, a native of Serradifalco (near Montedoro), Sicily, had a lengthy criminal background that included being caught in 1908 in the act of placing a Black Hand bomb, an offense that earned him a five-year sentence in Sing Sing Prison (he reportedly served just two years).

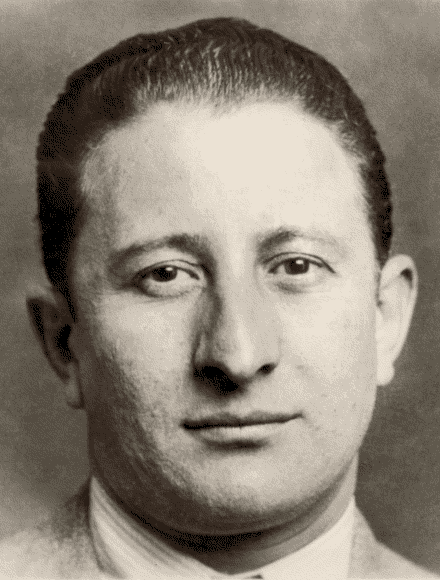

Pinzolo

After his release from prison, Pinzolo married Carmela Riccobono, making him an in-law to "Staten Island Joe" Riccobono, member of the Mafia organization that would later become known as the Gambino Crime Family. Pinzolo may have further enhanced his underworld standing by maintaining connections with other Serradifalco-born mafiosi outside of New York City in such areas as Buffalo, New York, and Pittston, Pennsylvania. [27]

Probably at least a member of the Reina group at the time of his elevation to the position of boss, Pinzolo was nevertheless regarded as an outsider by much of the organization. Lucchese and fellow Reina lieutenant Tommaso Gagliano personally disliked Pinzolo and resented Masseria's meddling in their internal business. Despite these feelings, they remained outwardly obedient and compliant, patiently awaiting an opportunity to strike.

Valachi recalled Pinzolo as a kind of Sicilian mafioso caricature, calling him a "greaseball" and noting he sported a long handlebar mustache (not present at the time of his 1908 arrest) and reeked of garlic. While Pinzolo's wife and five children lived at 8516 Twenty-fourth Avenue in Brooklyn, Pinzolo spent at least some of his nights at a hotel in lower Manhattan. [28]

Lucchese formed a business partnership with new boss Pinzolo, the California Dried Fruit Importers, which resold dried grape "wine bricks." In spring 1930, Lucchese rented office space for the venture on the tenth floor of the Brokaw Building, occupying 1457 through 1463 Broadway at Times Square. (The wine brick was a condensed grape product that, when mixed with water and allowed to ferment, could produce wine.)

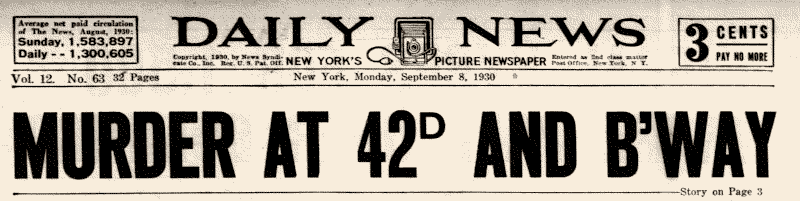

NY Daily News, Sept. 8, 1930.

The lifeless body of Joe Pinzolo was found in the office by a cleaning crew at shortly after nine o'clock on Friday night, September 5, 1930. Authorities determined that Pinzolo had been dead between five and nine hours by that time and speculated that the noise of daytime traffic in the streets below prevented anyone from hearing the gunshots that took his life. A .32-caliber revolver with six exploded shells was found discarded in an adjoining office.

Pinzolo's remains are carried from the Brokaw Building (NY Daily News).

Reports of the placement of Pinzolo's bullet wounds varied according to the source. The New York Daily News reported that there were two wounds in the neck and one in the chest, just above the heart. The Brooklyn Daily Times, however, reported a total of five wounds - two in the back, two in the chest and one in the side.

Police immediately went in search of Lucchese, known to be Pinzolo's partner and the lease holder on the office. But he was missing. Family members at the Lucchese home, 2069 Second Avenue, told investigators that Lucchese had left the city that morning and would be away for the weekend. [29]

Early the next week, Lucchese appeared at the district attorney's office reportedly accompanied by his legal counsel, former Judge Francis X. Mancuso. Lucchese was questioned and arrested on suspicion of homicide. Prosecutors had insufficient evidence to convince a grand jury to indict, and the charge was dropped. [30]

With Pinzolo's assassination, Joe the Boss had lost two key allies in just three weeks. Back on August 15, unknown gunmen had burst into an East Harlem office and murdered trusted Masseria adviser Giuseppe Morello. Convinced that a secret rebellion was occurring, Masseria called a meeting of New York mafiosi at a Staten Island location.

Mafia soldier Stefano Rannelli described the situation to Joseph Valachi, then a non-member associate of the Pinzolo organization:

...We are fighting Joe the Boss. Now Joe the Boss killed our boss then he put this guy Joe Pinzola in his place without us having anything to say about it, so we killed him. Now they are calling a meet they figure that whoever don't show up is guilty, but we are going to fool them as we are going to show up. By us showing up we throw the suspicion off of us...

Lucchese's out-of-town alibi was apparently sufficient to convince his underworld colleagues that he had nothing to do with setting up Pinzolo. A few days after the meeting, Valachi was told that Masseria was "in the dark" as to who killed Morello and Pinzolo. [31] Valachi later learned that Girolamo "Bobby Doyle" Santuccio was the gunman who murdered Pinzolo. [32]

Gagliano

Anti-Masseria forces in the Bronx and East Harlem lined up behind Tommaso Gagliano. Soon they discovered that a separate rebel group was coalescing around Salvatore Maranzano, a charismatic Mafia leader from Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily. While the Gagliano group had arranged the murder of Pinzolo, a Maranzano team led by Sebastiano "Buster" Domingo had taken care of Morello. The two rebel organizations met and arranged to work together behind Maranzano's leadership to fight Masseria. The rebels gained support of anti-Masseria mafiosi around the country. [33]

During the conflict known as the Castellammarese War, Joseph Valachi was inducted as a full member of the Maranzano-Gagliano faction of the Mafia and got to know Lucchese. According to Valachi, Lucchese was extremely generous. He later recalled, "There ain't a man on Earth that is loose with money like Tommie... You can never pick up a tab if Tommie is around." While working with Maranzano's rebel group, Valachi was ordered not to engage in his usual line of work: burglary. Lucchese apparently understood Valachi's sacrifice and regularly sent him money. [34]

Masseria

The war concluded with the assassination of Masseria by his own lieutenants on April 15, 1931. Through some manipulation, Maranzano secured for himself the role of boss of bosses. Maranzano called New York mafiosi together for a meeting at a Bronx dance hall and announced new leadership for regional Mafia families. Tommaso Gagliano was installed as boss over the Bronx-based organization formerly commanded by Reina and Pinzolo. Gagliano became the third man in a period of about fourteen months to officially command that organization. Thomas Lucchese got the nod as Gagliano's underboss. [35]

Some of Lucchese's underworld connections were documented when Cleveland police found him sitting ringside with Salvatore "Charlie Luciano" Lucania and Joseph Biondo at the July 3, 1931, heavyweight boxing match between champion Max Schmeling and challenger William "Young" Stribling. The three New York crime figures (representing different organizations later known as the Lucchese, Genovese and Gambino families) were taken in for questioning, fingerprinted and released. [36]

In New York City, Gagliano and Lucchese, and Frank Scalise (boss of an organization overlapping Queens and the Bronx) were close confidants of the new boss of bosses and regularly visited Maranzano at his new office on the ninth floor of the New York Central Building, 230 Park Avenue. [37]

Scalise

They and other Maranzano allies became aware that Maranzano was scheming to eliminate Mafia chieftains he viewed as obstacles. Salvatore Lucania, who became leader of the former Masseria organization in Manhattan, and Al Capone, boss of the Chicago Outfit, were on a list of Maranzano targets. [38]

At one point, Frank Scalise became convinced that he had made the list as well. Criticized by Maranzano for failing a secret assignment to murder mafioso Vincent Mangano, Scalise was called by the new boss of bosses to a meeting in Buffalo, New York. As Scalise arrived, he grew fearful that he was being put "on the spot" and quickly returned to New York, where he told underworld colleagues about Maranzano's hit list. [39]

Lucania may have learned of Maranzano's scheme through Joseph Biondo, but his source also may have been Thomas Lucchese. Lucania immediately began plotting Maranzano's assassination, and, according to Bonanno, Lucchese provided him with useful information about Maranzano's "office habits." Some assistance may also have been provided by Stefano Magaddino, boss of a crime family based in Buffalo, New York. Once the underworld superior of Maranzano, Magaddino found himself financially drained and repeatedly ridiculed by the new boss of bosses. According to Bonanno, Magaddino had been quietly scheming against Maranzano. [40]

Both Lucchese and Gagliano were at Maranzano's Manhattan office on September 10, 1931. (Years later, Lucchese explained to New York State's Crime Commission that he and Gagliano may have stopped by to discuss a building construction project or to sell sweepstakes tickets.) "Bobby Doyle" Santuccio was also present. On that afternoon, Lucania-allied Jewish mobsters posing as federal agents showed up, brought Maranzano into an inner office and stabbed and shot him to death. "Bobby Doyle" Santuccio, clearly shocked by the assassination, was discovered in the office by police and taken in for questioning. [41]

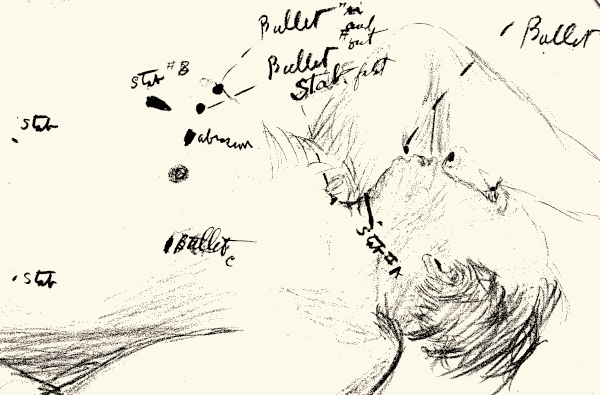

Coroner sketch showing placement of Maranzano wounds.

Sam "Red" Levine, one of the Jewish gunmen participating in the Maranzano assassination, was on his way out of the New York Central Building after the job when he saw Vincent Coll entering for a meeting with Maranzano. Maranzano had recently hired Coll to take care of the murder of Lucania. [42] Thanks to the assistance provided by those who were close to Maranzano and willing to betray him, Lucania was quicker on the draw.

Peace was quickly restored to the underworld at a Chicago convention where Scalise revealed Maranzano's plotting and Lucania argued that he moved against the boss of bosses only as an act of self-defense.

At the convention, U.S. mafiosi discarded the traditional "boss of bosses" dispute resolution role in favor of a new representative "Commission." The Commission included the bosses of the five New York City-based crime families - then Lucania, Tommaso Gagliano, Vincent Mangano (who replaced Frank Scalise), Joseph Bonanno (who succeeded Maranzano) and Joseph Profaci - along with the boss of Chicago, Al Capone, and the boss of Cleveland, Frank Milano. (An early shakeup seems to have caused Milano to be replaced by Buffalo boss Magaddino.) [43]

Following the end of the Castellammarese War, a second child, daughter Frances, was born to Thomas and Concetta Lucchese. In April of 1934, Lucchese's sister Rosalie married Joseph "Joe Palisades" Rosato, Lucchese's codefendant in the Louis Cerasuolo murder case. [44]

At that time, Lucchese was second-in-command, underboss, of the Gagliano organization. He also was regarded as chief of the 107th Street Mob, which had completely shed its earlier street gang status and was viewed by authorities as an arm of the Mafia.

Coppola

A Federal Bureau of Narcotics investigation decided that Dominick "the Gap" Petrelli and Michael "Trigger Mike" Coppola were Lucchese lieutenants in the 107th Street Mob and that Lucchese answered to Ciro Terranova. This suggests that the racketeers at 107th Street remained divided in their loyalties. Petrelli was known to work for the Gagliano-Lucchese organization. But Coppola was a top man in the crime family of Lucania, Terranova, Vito Genovese and Frank Costello, later known as the Genovese Crime Family.

Publicly, Lucchese held a number of jobs during the mid- to late-1930s. He was said to be an employee of the Interborough Window Cleaning Company owned by Hyman Stern and later to be associated with the V&L Hat Company on Manhattan's West 39th Street. [45]

Less publicly, he pursued new rackets in the post-Prohibition Era and became involved in legitimate and borderline businesses. He is believed to have been a behind-the-scenes force in some popular night spots and reportedly helped to bring top name entertainers, such as Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle and Benny Goodman, to the underworld-controlled Casino de Paree on Fifty-fourth Street in Manhattan.

(Lucchese also was said to have a strong relationship with crooner Frank Sinatra, who counted a large number of mafiosi among his friends. Sinatra attorney Mickey Rudin later confirmed for government investigators that the singer was familiar with "Gaetano Lucchese, Sam Giancana and Joseph Fischetti." Sinatra acknowledged knowing Lucchese but insisted they were no more than acquaintainces, having met "once or twice a long time ago.")

He became deeply interested in gambling rackets. Using his brother Giuseppe "Joseph Brown" Lucchese as an intermediary and Joseph "Joey Narrows" Laratro as a front man, Lucchese came to control a lucrative floating craps game on Manhattan's Lower East Side and extensive gambling operations, including a Corona-based policy racket, in the Borough of Queens.

His underworld role was not unknown to the authorities, who arrested him on November 18, 1935. The official charge against Lucchese - then booked as "Lucase" - was vagrancy. It was common at the time for New York police to use a vagrancy charge as justification for picking up and questioning underworld figures. [46]

Lucchese's father Baldassare, then a resident of 100-18 Northern Boulevard in Corona, Queens, died May 22, 1936. He was sixty-seven years old. He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, Queens, five days later. [47]

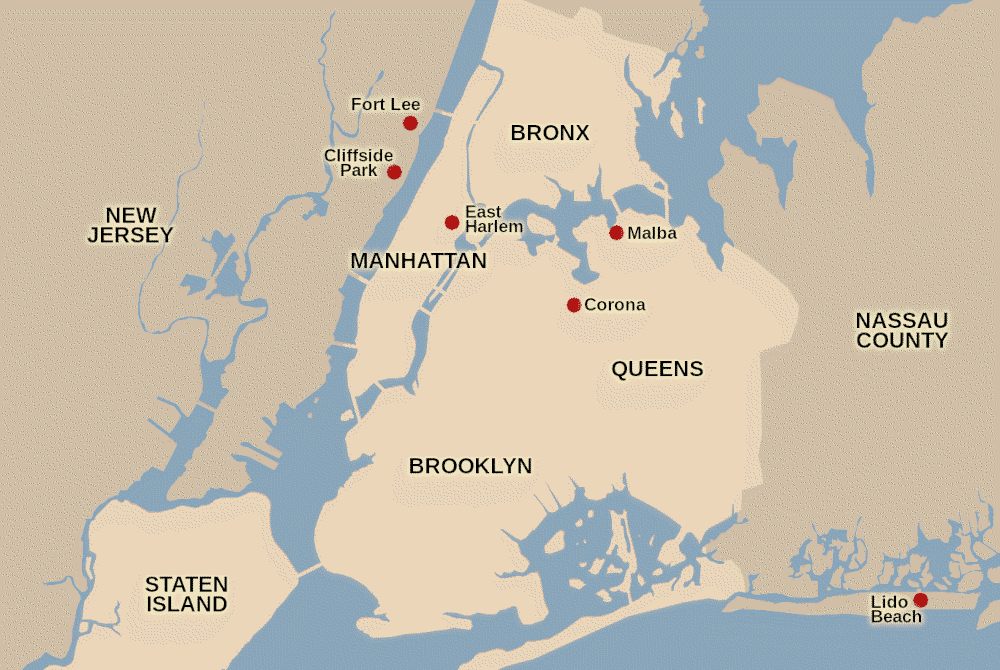

A short time later, Lucchese declared his intention to become a United States citizen. He also began planning to relocate his immediate family out of Queens and out of New York City entirely. He chose 1093 Briar Way, in the southern outskirts of Fort Lee, New Jersey, as the new address.

Lucchese in 1936

The site sat in an upscale residential neighborhood close to the intersection of Palisade Avenue and Central Boulevard. The same neighborhood had formerly been home to Giuseppe Morello, the Mafia leader murdered in 1930. The area was also host to the popular Palisades Amusement Park. Lucchese's house sat less than two miles from the George Washington Bridge, connecting New Jersey to Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. [48]

The Briar Way address was noted on U.S. census records in 1940. Lucchese, using the "Luckese" spelling, reported vaguely for the census that he was working as a contractor in his own business. [49]

Other New York-area Mafia leaders moved to the same area. These eventually included Albert Anastasia, Giuseppe "Joe Adonis" Doto, Guarino "Willie Moore" Moretti and Anthony "Tony Bender" Strollo. By the early 1940s, New York mafiosi were settling inter-family disputes through regular meetings held at Duke's Restaurant on Palisades Avenue in Cliffside Park, New Jersey, south of Fort Lee.

George H. White with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics raided Duke's on March 31, 1941, arresting and questioning a number of gathered mobsters, including Lucchese, Guarino and Salvatore Moretti, and narcotics racketeer Salvatore Arcidiaco. [50] Years later, White recalled the raid in court testimony:

...I raided a place known as Duke's Bar and Grill in New Jersey, which was a known rendezvous for important criminals in the New Jersey and New York area. At that time I - one Friday evening - the exact date I can't recall - I went there with several other narcotic agents and two New York police officers and we questioned everyone in the place. At that time, we found Tommy Brown - Gaetano Luchese, or Tommy Luckese - in company with Willie Moretti, also known as Willie Moore; Willie Moore's brother Salvatore, commonly known as Solly; a man by the name of Salvatore Arcidiaco, I believe, a well-known narcotic violator. These people were together at that time, although there were numerous other persons present in the restaurant. I questioned Luckese at that time... and he told me that he lived in New Jersey, I think in Briarway Street... and that he was in the construction business and that he had come over there to discuss his construction business with Moretti. [51]

As Lucchese's naturalization petition was being considered in November of that year, an examiner with the Naturalization Service asked him about any run-ins he may have had with the police. Lucchese stated falsely that, aside from the 1921 car theft case, he had never been arrested or charged. [52]

His naturalization petition was filed at U.S. District Court in Newark, New Jersey, on November 21, 1941. For the petition, Lucchese described his employment simply as "executive." His naturalization was approved two months later. Shortly after that, he acquired a home at 106 Parsons Boulevard in Malba, Queens. The home sat close the Whitestone Bridge, running across the East River and connecting Queens to the Bronx. [53]

The "executive" position mentioned on his naturalization document may have been with Grand View Construction Company, with which he was associated between 1943 and 1945. Grand View performed a number of small building jobs in New York City. In 1945, Lucchese first became involved in the garment industry. He was connected with the Braunell women's clothing company of 225 West Thirty-seventh Street between about 1947 and 1951. [54]

While Lucchese was becoming involved in clothing businesses and garment industry rackets, his old pal Lucania (convicted of compulsory prostitution in a 1936 case) was deported to Italy, attempted to relocate to Cuba and was returned to Italy. Italian police reportedly found a list of U.S. underworld contacts in Lucania's possession in 1949. The list included Willie Moretti, Joseph Biondo, Michael Coppola, Joseph Profaci, Philip Mangano, Anthony "the Chief" Bonasera and Thomas Lucchese. With Lucchese's name was an address, 55 Houston Street in Manhattan. That was the location of Bentivenga's restaurant, a known Lucchese hangout. [55]

Impellitteri

Lucchese's name was also mentioned in 1949-1950 in connection with campaigns for New York City mayor. He was said to be a close supporter of Vincent R. Impellitteri. Impellitteri was not seriously considered as a mayoral contender by Tammany Hall Democrats but, as leader of the city council, he became acting mayor following William O'Dwyer's resignation in August 1950. Ignoring the "acting" incumbent, the Democratic organization backed Judge Ferdinand Pecora in the 1950 election for a full term, and Edward Corsi was nominated by the Republican Party. Impellitteri ran as an independent and won a surprising victory (Pecora finished a close second, and Corsi a distant third).

For this election, Lucchese obtained a "good conduct certificate" from the New York Parole Board, finding that he had been on his best behavior since serving his 1922 grand larceny sentence, and recovered his right to vote. [56]

Corsi protested loudly that underworld figures, meeting at Duke's restaurant, had selected his opposing candidates. He claimed a strong Mafia faction led by Frank Costello and Joe Adonis backed Pecora while a Lucchese-led faction backed Impellitteri. [57]

Impellitteri denied any corrupt connection with Lucchese. And there was little evidence in support of Corsi's accusations. A newspaper report discovered that Lucchese and Impellitteri sat at the same ten-person Waldorf-Astoria table during the October 1946 Alfred W. Smith Memorial Foundation dinner, but could not manage to find anything more damaging. [58]

Tommaso Gagliano died of natural causes on February 16, 1951. He was sixty-six years old. He had been nominal boss of the Bronx-based Mafia organization for two decades, but had remained largely behind the scenes. After getting caught up in a building contractors racket in the Bronx in the early 1930s, he appears to have allowed Lucchese to control day-to-day crime family operations and to represent the Gagliano organization in dealings with other crime families. [59]

A longtime resident of 638 East 227th Street in the Wakefield section of the east Bronx, Gagliano and his wife moved a few miles north to 168 Seminary Avenue in Yonkers in later years. His wake was held at the East End Funeral Home on Gunhill Road, close to his old Bronx neighborhood. A February 20, 1951, funeral Mass was celebrated at Our Lady of Grace Church, 226th Street and Bronxwood Avenue. [60]

Though Lucchese likely had been overseeing crime family activity for years, his formal elevation to the boss role following Gagliano's death suddenly made him the subject of intense law enforcement scrutiny. His first known reaction was to try to find a peaceful refuge.

Lucchese's crime family administration reportedly included Stefano LaSalle as underboss and Vincent Rao as consigliere. Group leaders included Anthony "Tony Ducks" Corallo and "Big John" Ormento. The organization was apparently closely linked with Teamsters leader James R. Hoffa through crime family soldier and labor racketeer John "Johnny Dio" Dioguardi. The FBI estimated that there were two hundred men affiliated with the Lucchese family, about one-fifth the strength of New York's largest organization run by Vincent Mangano. [61]

In the summer of 1952, Lucchese and family settled into a new vacation home, 74 Royat Street in the exclusive oceanfront Lido Beach community on the Long Beach barrier island south of Long Island. Unlike many of Lucchese's other addresses, this seems to have been selected not for its easy commute but for its remoteness. [62]

Lucchese in 1950s.

However, Lucchese was well within reach of New York investigators. He was called in August for a private interview with the state's Crime Commission. His closed-door testimony was read into the public hearings of the panel in November and got into the New York newspapers.

In addition to outlining his life story to that point, the Crime Commission pressed Lucchese to discuss his relationships with known underworld characters: Gagliano, Pinzolo, Maranzano, Costello, Lucania, Adonis, Moretti, Coppola, Meyer Lansky, John Ormento, Andino "Pop Wilson" Pappadio, Joey Rao, Salvatore "Sally Shields" Shillitani, Abner "Longie" Zwillman. He denied knowing some others, such as Vito Genovese, Vincent Mangano, Stefano Magaddino, Anthony Strollo and Joseph Magliocco.

He could not explain why Lucania's contact list had his name and the address of Bentivenga's restaurant. He said he knew Lucania years earlier, but "he never wrote to me, I never write to him."

The commission brought out a Lucchese connection with west coast Mafia leaders Jack, Louis and Tom Dragna. Lucchese's telephone number was found to be in the possession of Tom Dragna during an arrest. Lucchese admitted a close relationship with Jack Dragna dating back many years. He noted that whenever he visited the west coast he spent "almost every day" with Jack Dragna.

(Lucchese was closely aligned with the Dragna Mafia organization based in Los Angeles. While the western region of the United States was generally represented on the Mafia Commission by Chicago's Outfit leader, Lucchese regularly stood up for Dragna's interests at Commission meetings. He did so even when it caused friction with the organization of Meyer Lansky, an important Mafia ally. When the Dragna Crime Family violently asserted a claim to a share of Las Vegas casino moneys skimmed by Lansky men, Lucchese defended the action. Las Vegas had been considered an "open city," but Lucchese is said to have supported Dragna claims that it was located within his official sphere of influence and therefore subject to taxation by his crime family.)

Jack Dragna

Lucchese denied any awareness of narcotics racketeering by any of his acquaintances, and he condemned the trade of illegal drugs: "Any man who got a family should die before he goes into any of that kind of business." [63]

(It may have been a convincing denial at that moment, but in the next decade, a U.S. Senate subcommittee was told that Lucchese lieutenant John Ormento was serving a long federal prison sentence for narcotics trafficking and 60 percent of known Lucchese Crime Family members had been arrested for a narcotics-related violation. [64])

The Crime Commission noted the reports of Lucchese's close relationship with Mayor Impellitteri and released information tying Lucchese with Myles J. Lane, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, and Thomas J. Murphy, who served as city police commissioner. [65]

At the same time, Lucchese's one-third ownership in the Braunell company was examined. Lucchese held the position of secretary-treasurer of the company. Investigators found that the company was led by respected businessman Louis Kaufman, but that its vice president was Joseph Lagano, who had served a federal prison term for dealing narcotics. [66]

Crime Commission and press attention to his underworld and overworld links appears to have prompted naturalization officials to reexamine Lucchese's citizenship papers. On November 17, 1952, the federal government began the process of denaturalizing Lucchese. Investigators determined that he made false statements about his criminal record, underreporting his arrests and lying about his use of aliases.

The government paperwork was filed awkwardly, however, and not strictly according to regulations. An Affidavit of Good Cause, created as a necessary prerequisite for the government complaint, was not immediately filed. Arguments over the proper filing and detail level of the affidavit dragged on in the courts for years. [67]

In late spring of 1953, Lucchese's daughter Frances married Thomas Gambino, oldest son of mafioso Carlo Gambino. Thomas Gambino went to work in the garment industry with Lucchese, who recently was installed as vice president of Monica Modes Inc. of 225 West 37th Street. [68]

Like Lucchese, Carlo Gambino was a Palermo-born mafioso. But Gambino was part of the former Mangano organization, commanded in the early 1950s by Albert Anastasia (who took over following the disappearance/murder of Mangano in 1951). Within the Anastasia organization, the Gambinos and the closely allied and related Castellanos, comprised a powerful Sicilian faction. [69]

Carlo Gambino

The union by marriage of the Lucchese and Gambino clans created an alliance that eventually upset the balance of power in the New York underworld and on the Mafia's Commission, according to Joseph Bonanno. [70]

The year 1957 was generally disastrous for the U.S. Mafia. (The year featured the start of the anti-rackets McClellan Committee, exposure of mob ties to the Teamsters, the assassinations of Frank Scalise and Albert Anastasia, the near-assassination and retirement of Frank Costello, the police breakup of the Apalachin convention and the entry of the FBI into the war against organized crime.) But it was a generally good year for Lucchese, who avoided attending the ill-fated convention at Apalachin, New York.

The denaturalization case against him was finally halted in that year, when the Second Circuit Court ruled in his favor. A lower court had decided that the government's complaint against Lucchese should be thrown out because it did not follow the specifics of the law. The government appealed to the Second Circuit and lost. The appeals court stated that an affidavit showing specific and substantial cause for the revocation of citizenship must exist before a denaturalization case can begin. [71]

The assassination of Anastasia in October left Lucchese in-law Carlo Gambino in position to take over Anastasia's crime family. One of the matters on the agenda of the 1957 Mafia convention at Apalachin may have been approval of Gambino's rise to boss. A Gambino rival, Armand Thomas Rava, hoped to take the boss position himself. Following the aborted convention, Rava mysteriously disappeared. A New York State investigation determined that Rava was never seen again after being picked up and questioned by police at Apalachin. (Years later, it was said that Gambino had Rava murdered in Florida.) Gambino seized control of the organization. [72]

The retirement of Costello allowed Vito Genovese to take control of the former Lucania crime family. Genovese, Lucchese and Gambino became a united voting bloc on the Commission. [73]

On July 3, 1958, Thomas Lucchese was called to testify before the U.S. Senate's Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field. While he declined to answer numerous questions, citing the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination, Lucchese did provide extensive personal and business background information.

Lucchese indicated that at the time of his appearance before the committee his primary job was president and half-owner of Harvic Sportswear Company with clothing factories in Scranton and Sweet Valley, Pennsylvania. His son, Baldassare, known as Robert, held the other half-interest in the company. The two factories had more than one hundred union employees, Lucchese said, and at that moment were shut down because of a strike. [74]

Kennedy

Questioned by committee Chief Counsel Robert F. Kennedy, Lucchese refused to say if he was involved in Budget Dress Corp., of 462 Seventh Avenue, in Sano Textiles, Inc., of 204 East 107th Street, or in Monica Modes, Inc., of 224 West 37th Street. Kennedy suggested that, while companies like Harvic had union workers, other companies operated non-union factories. "Can you explain at all to the committee why some of these dress shops that are operating in New York City and Pennsylvania, why some of them are organized and some of them aren't organized?" Kennedy asked. Lucchese declined to answer.

"Is it necessary," asked Kennedy, "to make any kind of a payoff in order to keep a shop unorganized?" Lucchese again declined to answer.

Chairman John L. McClellan stated, "We have information, and I think we probably already have established by some proof, at least, that in some instances they are able, either by knowing the right people or by payoff, to prevent a shop from being organized, and ... workers in that shop are paid less and the cost of producing is therefore less, and that particular shop or that management or ownership then can very successfully compete with competitors and sometimes even drive them out of business..."

Lucchese declined to make any statement on the matter. [75]

While clearly frustrated at Lucchese's refusals to address matters of concern to the committee, Kennedy noted that Lucchese's level of cooperation was unprecedented: "You answered more questions than any of your associates..." [76]

Vito Genovese was arrested on drug-related charges a few days after Lucchese's McClellan Committee appearance. He and fourteen others were convicted April 3, 1959, of narcotics conspiracy. Genovese was sentenced April 17 to fifteen years in federal prison. His sentence began on February 11, 1960, while he awaited word on his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. [77] In his absence, several leading figures competed and cooperated to oversee operations of his crime family and serve as Genovese's representative on the Commission.

Profaci

In 1961, a revolt erupted within the Profaci Crime Family. A faction led by Larry, Joey and Albert Gallo kidnapped a number of Profaci's top men in order to extort concessions from the boss. Reports indicated that the Gallo rebellion was encouraged and supported by Genovese lieutenant Anthony Strollo and by Carlo Gambino (and more remotely by Gambino ally Lucchese).

Profaci agreed to a number of demands in order to achieve the release of the kidnap victims, and then he went right back to the business practices the Gallos found unacceptable. [78]

Gambino caused the Gallos' complaints to be heard by the Mafia Commission early in 1962. He and Lucchese argued that Profaci was too old and out of touch to handle the Gallos effectively. They suggested Profaci retire. Profaci insisted that he had no intention of leaving his position, and the Commission supported him. But his term as boss concluded just months later, as Profaci succumbed to cancer on June 6, 1962. [79]

Magliocco

Profaci in-law Giuseppe Magliocco attempted to take command of the crime family, but the Commission hesitated to recognize him as a boss or as a Commission member. The Commission at that moment included New York bosses Lucchese, Gambino and Bonanno, along with a representative from the Genovese organization, Stefano Magaddino of Buffalo, Sam Giancana of Chicago and new additions Joe Zerilli of Detroit and Angelo Bruno of Philadelphia.

Magliocco's only real support came from Bonanno. Lucchese, Gambino and Magaddino were of like mind and strongly opposed. The strength of their unity drew in Giancana, Bruno and the Genovese representative. Zerilli sat on the fence.

Bonanno noted, "Lucchese and his ally Gambino now held majority power on the Commission." [80]

The Commission's lack of support for Magliocco encouraged further rebellion from the Gallo group. Magliocco saw his internal crime family division as the result of meddling by Gambino and Lucchese. Magliocco, probably with the support of Bonanno (who denied any involvement), schemed against the intrusive bosses. Magliocco made use of a spy obtained through his lieutenant Joseph Colombo.

In the summer of 1963, Colombo betrayed Magliocco and informed Gambino of his boss's actions, indicating that Magliocco was planning to assassinate both Gambino and Lucchese. [81]

With this information, the Lucchese-Gambino-dominated Commission was able to force Magliocco to step down from the leadership of his crime family and to retire in September of 1963. The Commission installed Joseph Colombo as the new boss of the organization. Magliocco died of natural causes a few months later. [82]

Mafia leaders in this period also faced unprecedented exposure, as Joseph Valachi began providing information to the U.S. Department of Justice. Valachi, an East Harlem burglar in his youth, became a member of the Maranzano rebellion during the Castellammarese War. He worked for Lucchese and Maranzano and became a member of Maranzano's personal guard following the war. After Maranzano's assassination, Valachi joined the Lucania organization, later known as the Genovese Crime Family.

Valachi testifies

While serving a prison sentence for narcotics racketeering in 1962, Valachi became convinced that Genovese was going to have him killed. Believing an approaching fellow inmate to be an assassin sent by the boss, Valachi beat the man to death. Facing murder charges and a Genovese murder contract, Valachi decided to talk to the government about the criminal society he knew as "cosa nostra." [83]

Foreseeing the impact of Valachi revelations, Lucchese appeared at the office of Nassau County District Attorney William Cahn on August 19, 1963. He spoke with Cahn for two hours, insisting that he was "never mixed up with anything illegal in my life." Cahn had access to Lucchese arrest records, and produced them.

Lucchese specifically denied belonging to any organization called "cosa nostra" (the term was not widely used by mafiosi at the time):

There's been a lot of publicity about me, and since I live in your county I thought you might want to talk to me. Valachi's crazy. I know nothing about any Cosa Nostra. The only think I belong to is the Knights of Columbus.

Lucchese also disputed reports that he had any role in the leadership of the former Profaci Crime Family based in Brooklyn. "I hardly ever get to Brooklyn," Lucchese said. "In fact I get lost in Brooklyn." [84]

As Valachi prepared to deliver public testimony before the Senate's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (McClellan Committee), the FBI released information relating to American organized crime and the bosses who controlled it. Early in September, 1963, a feature published in U.S. newspapers revealed the bosses believed to serve on the Mafia Commission, providing short biographies and photos of them.

Lucchese was said to be a New York City crime boss serving on the Commission, and he was described as the panel's overseer of prizefighting rackets. [85]

Lucchese

Joseph Valachi publicly testified before the McClellan Committee in October 1963. While not a focus of the testimony, Lucchese was discussed. His criminal record, including the 1921 grand larceny conviction and the 1927 arrest for receiving stolen property was read into the record. His connection to the 1930 murder of Joseph Pinzolo was recalled.

Confronted with Lucchese's continued leadership in the U.S. criminal society, Senator Jacob K. Javitz noted that Lucchese had managed to avoid any charges for a period of twenty-eight years. Javitz said that was "one of the most important things we've uncovered in this area." [86]

Another committee witness, New York Police Deputy Chief Inspector John J. Shanley, testified that Lucchese was rumored to hold gambling interests in the Saratoga area of upstate New York, to have investments in prominent entertainers and to be involved in New York waterfront rackets. Shanley said Lucchese had interests in a number of clothing companies, including Turbo Co., Gaucho LaForta Dresses, Amy DeFashion, Laurie Sportswear, Bewood Contracting, Debbie Petites, Budget Dress and Sherwood Fashions. Some of the firms were union shops, while others were not. Law enforcement considered some of the companies to be merely fronts for illegal activity. [87]

Valachi revealed that he once held his own interest in a non-union clothing manufacturer. He told the committee that whenever "any union organizer came around, all I had to do was call up John Dio or Tommy Dio and all my troubles were straightened out." The "Dios," whose full surname was Dioguardi, were important men in the Lucchese organization. [88]

Lucchese apparently was in poor health in the early 1960s. Bonanno noticed some deterioration during the 1962 Commission meeting relating to the Gallo-Profaci War, but he attributed it to the pressures of involvement in the underworld of New York City, a place he referred to as "the Volcano":

The Volcano had taken its toll on Lucchese. His face was beginning to sag. His hair had thinned. Age had drooped his varnished features. [89]

In the middle of the decade, law enforcement noted that Lucchese was largely absent. Ralph Salerno, head of NYPD's Central Investigations Division, learned the cause:

Mr. Lucchese one of the leaders of one of the five families located in the city of New York had been stricken and taken ill. We were able to learn that the prognosis was very bad for him, that he had an inoperable brain cancer and could not be expected to live more than three to six months, which turned out to be the case in fact. [90]

Lucchese entered Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in the summer of 1965 and had surgery for a brain tumor. He remained at the hospital's Harkness Pavilion for some time after the surgery and also reportedly received treatment for a heart condition. [91]

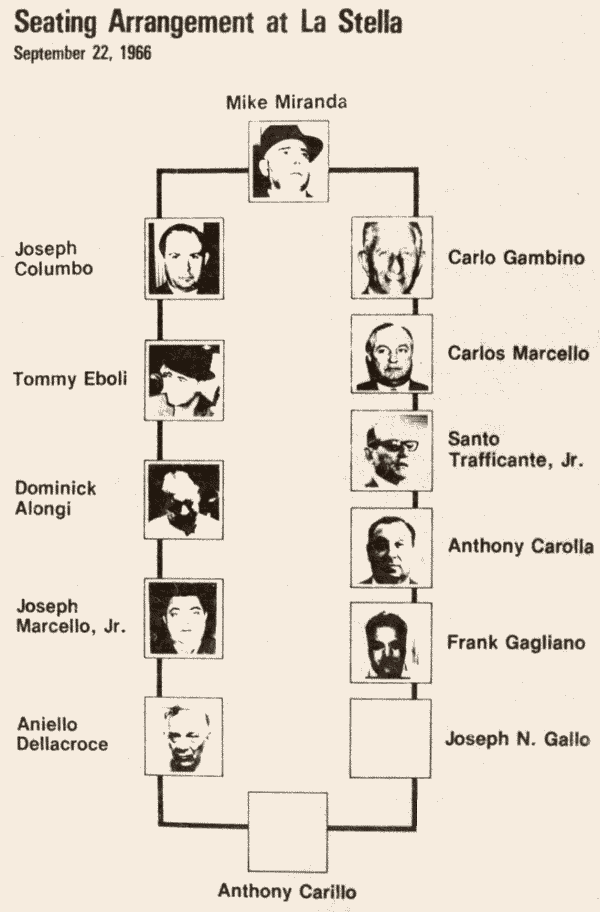

Attendees at La Stella meeting.

Lucchese's serious illness caused law enforcement to misinterpret a Mafia gathering in Queens, New York, in 1966.

Knowing Lucchese was near death, New York Police expected a new boss to be chosen and for the selection to require approval of the Commission. They guessed that Mike Miranda, a senior figure in the Genovese Crime Family, would be a participant in the Commission meeting.

According to Salerno, police noted that Miranda on September 22, 1966, entered the basement dining room of the La Stella restaurant, 102-11 Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills, Queens, followed by Carlo Gambino, mobster Joseph Gallo and Tampa boss Santo Trafficante. The police felt they were witnessing the expected meeting and arranged to raid the restaurant. [92]

New York detectives entered the restaurant's basement room and found thirteen known crime figures sitting around four dining tables placed together in the center of the room. The mobsters made no effort to resist as they were placed under arrest for consorting and transported to the precinct house in Maspeth. Among the suspects were leaders of the Genovese, Gambino and Lucchese crime families of New York, bosses from Tampa and New Orleans and other mafiosi. [93]

The suspects remained silent on the reason for the gathering. Police and press suggested a number of reasons but gave most attention to Salerno's view:

It was learned that top police sources suspect that the meeting was called to divide up territory controlled by Luchese, of Atlantic Beach, to expand gambling operations in Louisiana, Florida and the islands of the Caribbean, and to increase the flow of narcotics from Deep South ports.

The police sources stressed the fact that no representatives from two of the five New York crime families were present at the meeting. The two unrepresented families were the Luchese family and the Joe Bonanno family... The Bonanno family has no interests in the South or the Carribbean and might locgically be excused, but the Luchese family has heavy interests in the area. Luchese is dying of a brain tumor in a New York hospital. [94]

(A couple of years later, an informant told the FBI that the meeting had actually been called by the active New York members of the Commission in order to resolve an internal problem in the New Orleans organization. [95])

On April 11, 1967, Lucchese was released from Columbia-Presbyterian and returned to his vacation home in Lido Beach. He died there about three months later on July 13, 1967. Though Lucchese reportedly spent the last two decades of his life insisting "he was really just a respectable, home-loving businessman," news accounts of his death all described him as a Mafia/cosa nostra boss. Reports said he passed away after never fully recovering from the brain tumor surgery. He was survived by his wife and their two grown children. [96]

New York Times, July 14, 1967.

The criminal organization that took his name - one that he participated in since his youth and commanded since the early 1950s - also survived him. Carmine Tramunti was in charge of its operations for several years until Anthony "Tony Ducks" Corallo took the reins in 1970. Corallo was removed from the New York underworld through the successful prosecution of the Commission Case in 1985.

Valachi reportedly attributed Lucchese's rise in the rackets to "a spectacular doublecross." [97] Valachi was thinking of the betrayal of boss of bosses Maranzano. But, actually, Lucchese's career was guided by several doublecrosses. It is an interesting exercise to speculate on the course of his underworld career and of Mafia history in New York and across the country if Lucchese had not repeatedly betrayed Mafia superiors in 1930 and 1931.

He appears to have taken an active role in setting up the murder that took the life of short-term Bronx boss Joseph Pinzolo in 1930. That murder may be viewed by some as more of an act of vengeance than betrayal, as Pinzolo was appointed by Masseria after the Masseria-ordered slaying of Reina. But Pinzolo did serve as Lucchese's formal boss, had no known role in bringing about Reina's death and appears to have been put on the spot through his business partnership with Lucchese.

The Pinzolo killing was a critical event that brought together opponents of the Masseria regime before the Castellammarese War erupted. Lucchese was one of the key Mafia leaders who turned on "Joe the Boss." Without Lucchese's support for and complicity with the anti-Masseria rebellion, it is conceivable that an East Harlem-Bronx underworld led by Pinzolo and Ciro Terranova would have solidly backed Masseria in the struggle against Maranzano.

Genovese

One year (and a few days) after Pinzolo's murder, Lucchese's betrayal of Castellamarese War victor Maranzano led to dramatic changes in the structure of the U.S. Mafia.

Though a trusted aide to boss of bosses Maranzano, sources indicate that Lucchese was part of the underworld grapevine that informed other Mafia chieftains that they were targeted for assassination by Maranzano and gave them details about Maranzano's movements. The information allowed the targets to plot the assassination of Maranzano before he was able to move against them. Lucchese's presence in the Maranzano offices at the moment of the assassination, though possibly coincidental, suggests a level of complicity in the execution of that plot.

With Maranzano gone, one serious threat to the continued existence of well known crime figures like Lucania, Capone and Genovese was removed. (Each of these soon made dramatic exits from their Mob roles - Lucania and Capone heading off to prison, and Genovese relocating to Italy for a time.) The lives and careers of other underworld leaders may also have been extended. According to Valachi, Maranzano's list of targets included Frank Costello, Willie Moretti, Joe Adonis, Vincent Mangano, Ciro Terranova and Dutch Schultz. [98]

Terranova

In addition, Maranzano's scheming and his assasination proved that the Mafia had outgrown the boss of bosses system and needed a new dispute-resolution mechanism. (This was an inescapable conclusion, as all four men who are known to have held full boss of bosses authority - Salvatore D'Aquila, Giuseppe Morello, Giuseppe Masseria, Salvatore Maranzano - were murdered in the period between October 1928 and September 1931. [99])

The result was the establishment of a representative Commission, including bosses from the largest and most influential crime families in the U.S. Though this system, too, had its flaws, the Commission managed to avoid large-scale gangland conflict for decades.

It is difficult to imagine the shape of the U.S. Mafia if Maranzano had lingered through 1931. Possibly the Mafia network would have disintegrated into constantly warring factions. Possibly it would have been streamlined into an efficient and ruthless syndicate entirely responsive to the commands of a single crime lord.

1 The Profaci-Colombo Crime Family is generally referred to as the smallest of the New York City-based Mafia organizations.

2 Gaetano Lucchese Naturalization Petition, no. 51852, U.S. District Court at Newark, New Jersey, Nov. 21, 1941, certificate no. 5701024 issued Jan. 25, 1943; Passenger manifest of S.S. Duca D'Aosta, departed Naples on Nov. 8, 1911, arrived New York City on Nov. 22, 1911; Gaetano Lucchese birth record, Brancaccio, Palermo, Sicily, vol. 189, no. 2698, Dec. 2, 1895, Ancestry.com; Marriage of Baldassare Lucchese and Francesca Cinquemani, Palermo, Italy, Marriages, Vol. 155, no. 54, Feb. 5, 1894, Ancestry.com.

Baldassare Lucchese was the son of Vincenzo and Rosalia Palazzotto Lucchese. It appears that Baldassare had been married once before to Teresa Sirchia, who died before 1891. They appear to have had at least one child together, Rosa, who died in infancy. (Cherry, Jennifer, "Buongiorno/Dicara-Piazza/Balestrieri" family tree, Ancestry.com.) The lack of a known Baldassare son named for Vincenzo raises the possibility that this earlier marriage also produced a son, so far unrevealed in searches of records.

3 Passenger manifest of S.S. Duca D'Aosta, departed Naples on Nov. 8, 1911, arrived New York City on Nov. 22, 1911; Record of detained aliens, S.S. Duca D'Aosta, arrived Nov. 22, 1911.

Records did not name the children held in quarantine. The detention document names "Cinquegrani, Francesca & 2 ch." but refers to manifest lines 8 through 13, which corresponded to Francesca and all the children except 16-year-old daughter Pietra. Antonino Calli was perhaps Francesca's uncle and Baldassare's in-law.

4 Passenger manifest of S.S. Canada, departed Palermo on Feb. 9, 1913, arrived New York on Feb. 21, 1913.; New York City insurance maps, New York Public Library.

The 332 East 106th Street address was the reported destination of a Vinzenzo Lucchese, 27, hairdresser, who was traveling from Italy to New York to join his uncle Baldassare Lucchese.

5 Feinberg, Alexander, "Analysis of is testimony before board unfolds unsavory record," New York Times, Nov. 22, 1952, p. 1.; Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, Part 1, View at mafiahistory.us.

Ciro Terranova, his Mafia colleagues and allied street gangsters worked in league with the organization of Jewish-American gangster Arthur "Dutch Schultz" Flegenheimer. Other local gangsters, and later the Bronx-based crime family named for Lucchese, sided with an anti-Schultz faction eventually led by the Irish-American Coll brothers.

6 Thomas Luckese World War I draft registration card, serial no. 105, order no. 3431, Local Board Division 152, New York City, New York, Sept. 12, 1918; United States Census of 1920, New York State, New York County, Assembly District 18, Enumeration District 1240; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3; Investigation of Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, Part 32, Hearings before the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field (McClellan Committee), U.S. Senate, 85th Congress, 2nd Session, Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1958, p. 12476.

In the McClellan Committee hearings, Lucchese recalled that he lost his index finger in an ammunition plant accident in 1915. Reid and Patterson, writing in 1952, placed the industrial accident in 1919. Lucchese's draft registration card from September 1918 makes no mention of the absence of his "trigger finger," but a question on physical disqualification from military service specifically asked about the loss of "arm, leg, hand, eye..."

7 "Suffolk jury finds auto thieves guilty," Brooklyn Standard Union, March 17, 1922, p. 14; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3.

Reid and Patterson reported inaccurately that Lucchese and Spina were arrested in the car just minutes after it was stolen. They also incorrectly reported that Lucchese and Spina were convicted on Jan. 19, 1922. That was weeks before they were indicted and two months before their trial occurred.

8 Investigation of Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, Part 32, Hearings before the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, U.S. Senate, 85th Congress, 2nd Session, Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1958, p. 12476; "Thomas Luchese, rackets boss called 3-Finger Brown, is dead," New York Times, July 14, 1967; Feinberg, Alexander, "Analysis of is testimony before board unfolds unsavory record," New York Times, Nov. 22, 1952, p. 1.

9 Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3.

10 "Indict Comez for murder," Brooklyn Daily Times, Feb. 16, 1922, p. 10; "Vail, Howell are grilled in court as writing experts," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 17, 1922, p. 14; "Suffolk jury finds auto thieves guilty," Brooklyn Standard Union, March 17, 1922, p. 14.

11 "Suffolk jury finds auto thieves guilty," Brooklyn Standard Union, March 17, 1922, p. 14; "Auto stealers get no mercy from county Judge Furman," Brooklyn Daily Times, March 28, 1922, p. 8.

12 Thomas Luckese, Sing Sing Prison Receiving Blotter, no. 73617, received March 28, 1922; Jack Spina, Sing Sing Prison Receiving Blotter, no. 73616, received March 28, 1922; Certificate of Good Conduct issued for Thomas Luckese by Board of Parole of the State of New York, dated April 18, 1950, filed April 19, 1950, copy published with Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is 3 Finger Brown? - Light on his private life," New York Daily News, Nov. 13, 1952, p. 3; "Thomas Luchese, rackets boss called 3-Finger Brown, is dead," New York Times, July 14, 1967.

13 New York State Census of 1925, New York County, Assembly District 18, Election District 15; Certificate of Good Conduct issued for Thomas Luckese by Board of Parole of the State of New York, dated April 18, 1950, filed April 19, 1950, copy published with Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is 3 Finger Brown? - Light on his private life," New York Daily News, Nov. 13, 1952, p. 3.

14 Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3.

15 Investigation of Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, Part 32, Hearings before the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, U.S. Senate, 85th Congress, 2nd Session, Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1958, p. 12477, 12485; United States of America v. Gaetano Lucchese, 247 F.2d 123 (2d Cir. 1957), argued March 15, 1957, decided June 17, 1957, Justia US Law, law.justia.com.

16 Concetta Vassalo, New York City Extracted Birth Index, certificate no. 33856, June 22, 1908; Concetta Vassallo Luckese, Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 086-44-0052, death date May 2, 2007; Gaetano Lucchese Naturalization Petition, no. 51852, U.S. District Court at Newark, New Jersey, Nov. 21, 1941, certificate no. 5701024 issued Jan. 25, 1943.

17 United States of America v. Gaetano Lucchese, 247 F.2d 123 (2d Cir. 1957), argued March 15, 1957, decided June 17, 1957, Justia US Law, law.justia.com; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3; Investigation of Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, Part 32, Hearings before the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, U.S. Senate, 85th Congress, 2nd Session, Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1958, p. 12477-12478.

This appears to be the Louis Cerasuolo who died in Manhattan on June 30, 1928. (Louis Cerasuolo, New York City Extracted Death Index, certificate no. 18181, Manhattan, New York, June 30, 1928.)

18 United States Census of 1930, New York, Queens County, Assembly District 3, Enumeration District 41-219.

19 United States Census of 1910, New York State, New York County, Ward 12, Enumeration District 338; Gaetano Reina World War I draft registration card, New York, NY, July 1917; United States Census of 1920, New York State, New York County, Ward 18, Enumeration District 1269; New York State Census of 1925, New York County, Assembly District 18, Election District 23; "Wealthy ice dealer slain in doorway," New York Times, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 3; Jarrell, Sanford, "Police save rival from wife's fury," New York Daily News, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 2; "Baff murder of 1915 echoes in new death," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 3; U.S. Census of 1930, New York State, Bronx County, Enumeration District 3-679.

20 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 112-114, mafiahistory.us.

Valachi referred to the Irish mob on a number of occasions. The pages noted above deal with a moment in which a feud erupted between members of an Irish and Italian gang and the Schultz-Terranova combination. Valachi momentarily found himself pulled in both directions.

21 Martin, John, "Vitale party $3,300 shy by holdup raid," New York Daily News, Dec. 9, 1929, p. 2.

22 "Vitale guests granted writ; hit '3d degree,'" Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 31, 1929, p.1.

23 Jarrell, Sanford, "Police save rival from wife's fury," New York Daily News, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 2.

24 "Baff murder of 1915 echoes in new death," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 3; "Wealthy ice dealer slain in doorway," New York Times, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 3; "Third man slain in ice rate war," Asbury Park NJ Evening Press, Feb. 27, 1930, p. 4.

25 Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 106.

26 "Two Schultz aides freed from jail," New York Times, July 27, 1935, p. 28.

The address of Bo Weinberg was noted when he was called as a witness in the Schultz's federal tax evasion trial at Malone, New York.

27 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 280-282; Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 106; "Catch Black Hander exploding a bomb," New York Times, July 15, 1908, p. 3; "Had a 'Black Hand' letter," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 15, 1908, p. 1; Bonaventura Pinzolo, Sing Sing Admission Register, no. 58534, received Oct. 17, 1908; New York City Marriage Index, 1866-1937, certificate no. 17807; Feather, Bill, "Gambino Family membership chart 1930-50's," Mafia Membership Charts, mafiamembershipcharts.blogspot.com, Nov. 11, 2017.

28 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 271-272; Cassidy, Tom, "Mystery man slain on B'way; speakie list hints vendetta," New York Daily News, Sept. 6, 1930, p. 3; "Scrubwomen find slain boro man in Manhattan office," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sept. 6, 1930, p. 22.

After Valachi was first introduced to "Joe" Pinzolo, Dominick "the Gap" Petrelli pulled Valachi aside and said, "He is going to die."

29 Cassidy, Tom, "Mystery man slain on B'way; speakie list hints vendetta," New York Daily News, Sept. 6, 1930, p. 3; "Scrubwomen find slain boro man in Manhattan office," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sept. 6, 1930, p. 22; "Boro man slain; rum feud seen," Brooklyn Daily Times, Sept. 6, 1930; "Luckese hunted in killing," New York Daily News, Sept. 7, 1930, p. 4.; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3.

30 United States of America v. Gaetano Lucchese, 247 F.2d 123 (2d Cir. 1957), argued March 15, 1957, decided June 17, 1957, Justia US Law, law.justia.com; Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics, Report of the Committee on Government Operations Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, United States Senate, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1965, p. 176; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3; "Thomas Luchese, rackets boss called 3-Finger Brown, is dead," New York Times, July 14, 1967.

31 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 280-282.

32 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 321.

33 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 280-282.

34 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 332-333, 337.

35 Valachi, Joseph, "The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra," unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 341-344.

36 United States of America v. Gaetano Lucchese, 247 F.2d 123 (2d Cir. 1957), argued March 15, 1957, decided June 17, 1957, Justia US Law, law.justia.com; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3.

37 Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 132-133.

38 Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing - Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, 1964, p. 362-363; Gentile, Nick, with Felice Chilante, Vita di Capomafia, Rome: Crescenzi Allendorf, 1993, p. 122; Flynn, James P., "La Cosa Nostra...," FBI report from New York Office, file no. CR 92-914-58, NARA no. 124-10337-10014, July 1, 1963, p. 16.

39 Gentile, Nick, with Felice Chilante, Vita di Capomafia, Rome: Crescenzi Allendorf, 1993, p. 122-123; Flynn, James P., "La Cosa Nostra...," FBI report from New York Office, file no. CR 92-914-58, NARA no. 124-10337-10014, July 1, 1963, p. 16.

40 Flynn, James P., "La Causa Nostra," FBI report of New York office, file no. CR 92-914-27, NARA no. 124-90149-10084, Jan. 31, 1963, p. 51; Gentile, Nick, with Felice Chilante, Vita di Capomafia, Rome: Crescenzi Allendorf, 1993, p. 122-123; Flynn, James P., "La Cosa Nostra...," FBI report from New York Office, file no. CR 92-914-58, NARA no. 124-10337-10014, July 1, 1963, p. 16; Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 133-135, 139.

41 New York State Crime Commission (Proskauer Commission), Public Hearings, No. 4, New York County, 1951, published 1952, cited in Critchley, David, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, New York: Routledge, 2009; Hortis, C. Alexander, The Mob and the City, Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2014; Reid, Ed, and Neal Patterson, "Who is Three Finger Brown?" New York Daily News, Nov. 10, 1952, p. 3; "Gang kills suspect in alien smuggling," New York Times, Sept. 11, 1931, p. 1; Feinberg, Alexander, "Analysis of is testimony before board unfolds unsavory record," New York Times, Nov. 22, 1952, p. 1.

42 Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing, Second Government: The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, 1964, p. 372-373; Maas, Peter, The Valachi Papers, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1968, p. 113-114; Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics, Part 1, Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, 88th Congress, 1st Session, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963, p. 231; Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 139.

Lucania, successor to Masseria, had become Ciro Terranova's superior. While the Castellammarese War was resolved with the assassination of Masseria, the Colls continued to war on the Terranova-Schultz organization. Maranzano's scheme to use Vincent Coll to murder Lucania could have shielded the boss of bosses from suspicion by making the killing appear related to the Coll war.

43 Bonanno, Joseph, with Sergio Lalli, A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, p. 138-141; Roberts, SA John W. Jr., "La Cosa Nostra Chicago Division," FBI report from Chicago Office, Dec. 13, 1963, pp. 2-3; Gentile, Nick, with Felice Chilante, Vita di Capomafia, Rome: Crescenzi Allendorf, 1993, p. 124; Flynn, James P., "La Cosa Nostra...," FBI report from New York Office, file no. CR 92-914-58, NARA no. 124-10337-10014, July 1, 1963, p. 9-10, 16-17.

44 Gaetano Lucchese Naturalization Petition, no. 51852, U.S. District Court at Newark, New Jersey, Nov. 21, 1941; Joseph Rosato and Rosalie Luchese, New York City Extracted Marriage Index, certificate no. 1208, Queens, New York, April 8, 1934.

In his naturalization petition, Lucchese indicated that his daughter was born June 4, 1931. Other records show a Frances Luckese born in Queens, New York, on May 20, 1931. See Frances Luckese, New York City Birth Index, 1910-1965, May 20, 1931, Ancestry.com.