Minor edits, additions and formatting changes were made to this article in May 2018 and December 2019. It was reformatted in December 2021.

Spinelli

In the late afternoon of March 20, 1912, Mrs. Pasquarella Musone Spinelli was fatally shot in an East Harlem structure the New York press later dubbed "the Murder Stable." [1] After Mrs. Spinelli's death, the lives of a number of stable-linked underworld figures also ended violently, and numerous legends about the building were born.

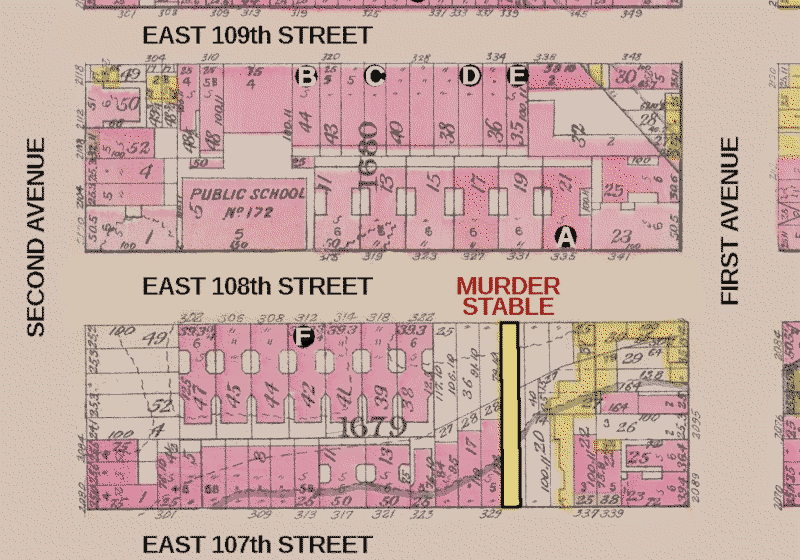

Located at 334 East 108th and pushing southward through the block to emerge on East 107th Street [2], the stable was part of a row of slapped-together, dark and dangerous-looking wooden shacks that ran from the middle of the block to the corner of First Avenue. [3] That row of buildings was becoming more and more conspicuous as the neighborhood dropped its earlier industrial identity and became residential. New, six-story brick tenements were springing up in formerly vacant lots and on a large adjacent property that had been home to a massive stone works business. [4]

The presence of Public School No. 172 [5] up the block and across the street could have contributed to the growth of the stable's terrifying legend, as the warnings of concerned neighborhood parents took root in fertile childhood imaginations. But, beginning on that March afternoon in 1912, there were reasons enough to steer clear of the stable.

Mrs. Spinelli, a resident of 335 East 108th Street, stepped out of her apartment building just before six o'clock and crossed the street to the livery stable she owned and managed. Performing a check of the facility and the horses boarded there was a daily ritual.

Spinelli's daughter, Nicolina "Nellie" Lener (also spelled "Lenere" and "Lenare") watched from the front window of the apartment as Spinelli crossed the street. Nellie noticed some moving silhouettes near a lantern within the building some distance from the entrance. A short time later, Nellie heard gunshots. She saw two men with pistols rush from the stable toward Second Avenue, force their way through a gathering crowd and disappear around the corner to the south. [6] She recognized one of the men as Aniello Prisco. [7]

NY Herald

21 Mar 1912

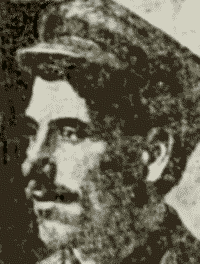

Prisco, known locally as "Zoppo" (Italian term meaning "lame") or "the Gimp," was the terror of East Harlem. He led a Neapolitan-American gang that was suspected of murders, robberies, extortion and other offenses. [8]

Prisco was born in Naples around 1880 and entered the United States in 1905, moving in with a cousin at First Avenue and East 109th Street.

He acquired his nickname and his distinctive gait in the spring of 1909, when he unwisely provoked a gangster known as "Scarface Charlie" Pandolfi. Pandolfi expressed his displeasure by firing a dozen slugs into Prisco's body. Doctors managed to save his life, but had trouble mending a badly shattered bone in his left leg. When the bone healed, Prisco's left leg was inches shorter than his right leg. [9]

It was generally assumed that Prisco spent much of the winter of 1911-1912 planning an attack against Pasquarella Spinelli due to a bloody incident in the autumn.

According to reports, on October 29, 1911, Spinelli's daughter Nellie was alone with twenty-four-year-old Prisco underling Frank "Tough Chick" Monaco when Monaco breathed his last.

The press speculated on the relationship between "Tough Chick" and Nellie. Some papers said they were sweethearts or former sweethearts. At least two papers reported that they were married. [10] (Monaco's death certificate indicated that he was single. [11])

Whatever their relationship, it was said that Monaco tried at that quiet moment with Nellie to gain access to the wealth stored in Pasquarella Spinelli's safe. As the young man knelt to open the safe, Nellie picked up a kitchen carving knife and stabbed Monaco repeatedly until he was dead. Very dead. A news report indicated that there were more than twenty stab wounds in Monaco's back.

Press accounts stated that, after thoroughly perforating Monaco, Lener walked down to the East 104th Street police station and reported that there was a dead man in her home. As she returned with police, she confessed that the man was dead because of her actions. [12]

An autopsy found that Monaco died of a hemorrhage following stab wounds to the lung and the heart. [13] Nellie was arrested. Within a few weeks, a coroner's jury decided that Nellie had been provoked into using violent defensive force and was not guilty of any prosecutable wrongdoing. [14] Aniello Prisco reportedly was not satisfied with that determination. The shooting death of Spinelli, despite her precautions, appeared to be Zoppo's revenge.

As the gunmen left the scene of Spinelli's murder, neighborhood residents, fearful but curious, assembled along the sidewalk. Nellie ran across the street and into the stable, where she was joined by stablehand Giovanni Ravvo. Ravvo had been working in the yard outside the building when he heard the shots.

They found Spinelli's dead body resting near the top of a wide ramp that led from the ground floor to the upper level of the ramshackle building, where the horse stalls were located. Ravvo summoned police. [15]

When authorities arrived, they saw that Spinelli had been struck by two bullets. One had entered the left of her neck, while the other penetrated her right temple and lodged in her brain. [16]

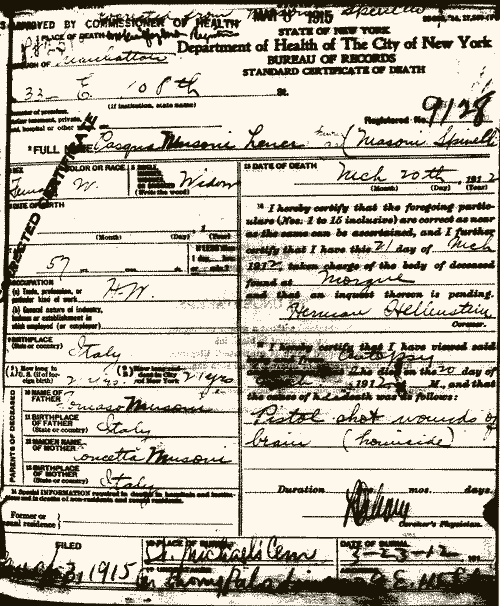

Following a post-mortem examination, a death certificate, issued in the name of "Pasqua Musoni Spinelli Lener," officially established the cause of death as "pistol shot wounds of brain (homicide)."

The document stated Mrs. Spinelli's age as fifty-seven. It noted that she was born in Italy to Tommaso and Concetta Musoni (Musone) and spent the last twenty-one years in the United States. [17]

Spinelli death certificate

Press reports of the killing labeled Spinelli the "Hetty Green" of Harlem's Little Italy. [18] The reference, far more easily understood in 1912 (when the original Hetty Green was still alive) than it is today, was to Henrietta Robinson Green. Nicknamed "the Witch of Wall Street," Green was a wealthy and notoriously miserly businesswoman who gathered riches through work, investments and inheritance.

Newspapers noted that Pasquarella Spinelli was the richest female in Harlem and owned stores, markets and tenement houses in addition to the extremely profitable stable. There was speculation that her wealth was not accumulated purely through legal means. Stories developed that many of the horses housed in and sold from her stable had been stolen by a group of young neighborhood hoodlums - a gang trained in criminal techniques by Spinelli herself. [19]

Spinelli was buried on March 23, 1912, at St. Michael's Cemetery. Funeral arrangements were handled by Anthony Paladino of East 115th Street. [20]

Mrs. Spinelli's background is a bit hazy, particularly with regard to her marital status. The few available records indicate that she traveled to America in 1892, at about the age of thirty-six, settling in Manhattan. [21] The 1905 New York State Census located her, then forty-nine, at 345 East 109th Street with a husband Pietro Spinelli, a fish dealer, and children Tommaso, 19, and Nicolina "Nellie,"" 16. [22]

Lener

When the federal census was taken in April 1910, Pasquarella showed up at 2097 First Avenue, between 107th and 108th Streets. The census indicated that she was living with her husband Pietro, the fish dealer, and her daughter Nicolina Lener, nineteen. Curiously, Pietro's name in this document is written as "Solazzo" rather than Spinelli.

The federal census revealed that Pietro was Pasquarella's second husband - they had been married for thirteen years, placing the date of their marriage no later than the spring of 1897. Nicolina Lener was said to be Pietro's step-daughter. Pasquarella was reported to have given birth to seven children, with six of those children still living at the time. Apparently, Pasquarella had been married previously to a man with the surname Lener, with whom she had children Nicolina, son Tommaso (no longer living with Spinelli by 1910) and the others. [23]

The identity of the earlier husband remained a mystery until May 2018, when a family historian provided details. According to the genealogist's research, Pasquarella was first married on December 9, 1872, to Domenico Lener, son of Nicola and Maria Teresa Scalera Lener, in Marcianise, Italy. [24] (It was not the only occasion of intermarriage between the Musone and Lener families of Marcianise. Domenico Lener's paternal grandmother was Francesca Raffaele Musone. Pasquarella's son, Clemente Lener, married Marcianise-born Rosa Musone in 1902. [25]) Nine children were born to the couple between 1873 and 1889. Nicolina was the last. [26]

Monaco

The marriage of Pasquarella and Domenico Lener experienced a long-distance separation when Pasquarella traveled to the United States in the company of her older brother Alessandro Musone in 1892. Domenico Lener died in Italy on May 27, 1898. [27]

If this information is correct, Pasquarella may still have been married to Domenico Lener at the time she and Pietro Spinelli were wed.

The family historian further noted that Nicolina Lener joined her mother in New York City following the death of Domenico.

Some of Pasquarella's other children settled in New York between the time of their mother's arrival and their father's death. Concetta, eleven; Clemente, nine; Tommaso, seven, sailed to New York with their relative Francesco Scalera in the spring of 1893. Tommaso became a blacksmith in East Harlem. At the time of his 1906 naturalization petition, he was living at 301 East 109th Street. (For some reason, during the naturalization process, New York County Justice Samuel Greenbaum suspected Tommaso Lener of underworld connections. Greenbaum asked if Tommaso's naturalization petition witness, insurance broker Salvatore Tartaglione was a member of the Mafia. Tartaglione said he was not.) [28]

In the brief period between the 1910 Census and Spinelli's murder, it appears that her fish-dealer husband Pietro passed away. (Spinelli's death certificate indicated that she was a widow). She briefly moved in with daughter Nellie at 239 East 109th Street, where "Tough Chick" Monaco was stabbed to death in 1911, and then moved again with Nellie to 335 East 108th Street.

Nellie was married during that time but not to Monaco. A story in the New York Times stated that she was wed in a civil ceremony at City Hall around 1910 to a man named Gaetano Napolitano. (The Lener family historian stated the marriage to Napolitano occurred on August 24, 1909.) The newlyweds did not cohabitate, according to the newspaper, because custom required a religious ceremony. Pasquarella Spinelli reportedly put the brakes on a church wedding until Napolitano could demonstrate the financial means to support a family. He demonstrated something entirely different by packing up and running away without his bride. [29]

Spinelli's "Murder Stable" and a gang that used it as a headquarters was vividly recalled many years later by Mafia turncoat Joseph Valachi. In Valachi's unpublished memoirs, he wrote that he grew up in East Harlem, next door to the Murder Stable.

Valachi was born to Neapolitan immigrants on September 22, 1903. He was just eight years old when Spinelli was murdered, but he had already had enough experience with her to know he "hated her."

Valachi's boyhood apartment was poorly furnished and infested with bedbugs. Some nights, Valachi and a neighborhood friend sneaked into the stable, despite its underworld connections, and made a comfortable bed for themselves in moving vans sheltered there.

"The boss of this stable mob believe it or not, was a woman," Valachi stated. "She had a mustache, and when she caught us sleeping in those vans believe me she would wake us up by hitting us on top of our heads with a broom handle. I hated her so much."

Valachi hated her enough to wish her dead. "I used to see her sitting down in front of the stable and I used to pray that someone would kill her. Well anyway it happened."

Young Valachi was in the crowd that gathered at the stable following the murder. "She was laying on the floor. I made it my business to get in there somehow and I just spit on her and said it's about time. I guess everybody was happy as she was a very mean woman."

Valachi remembered that the reputation of the Murder Stable neighborhood made it impossible for him to find employment early on. "I couldn't get a decent job as the murder stable was constantly in the newspapers at this time - always someone was getting killed... The question would be, where do you live? Well I would say 312 E. 108th Street. They would snap back and say no we don't need anyone. Some would say that's where the murder stable is, nope we don't need anyone." [Note: 312 E. 108th Street was not directly next door to the stable but a few doors away, in a group of homes recently constructed on property formerly used by a stone works.]

The murder of Spinelli was still being talked about in East Harlem when Valachi was in his mid-twenties. At that time, the rumor was that Spinelli was killed because she - not Nellie - was directly responsible for the killing of Monaco.

"This is what I was told," Valachi related. "[Spinelli] had a beautiful daughter and one of the boys raped her. When the old woman found out about it she stabbed this fellow to death." Valachi recalled that the stabbed fellow had an important friend, who "was doing time at the time of his friend's death, but when he came out he killed this woman with a shotgun." [30]

The story shared with Valachi differs in a number of ways from official and press accounts of the Spinelli murder. However, the claim that Spinelli rather than her daughter was responsible for the stabbing death of Monaco explains why Spinelli was targeted by the vengeful Prisco.

Murder Stable location (edited version of NY Public Library insurance map from 1911).

A - 335 East 108th Street: Residence of Pasquarella Spinella at the time of her murder, and of Joseph "Joe Pep" Viserti. Spinella business partner Luigi Lazazaro lived next door at 337 East 108th Street at the time of his arrest in connection with the Spinelli killing.

B - 318 East 109th Street: Residence and coffeehouse of Giosue Gallucci, site of Genaro Gallucci's killing in 1909, site of Aniello Prisco killing in 1912.

C - 324 East 109th Street: Residence of Fortunato LoMonte in 1890s.

D - 332 East 109th Street: Childhood home of Guarino "Willie Moore" Moretti.

E - 336 East 109th Street: Cafe run by Giuseppe Jacko in 1912, location of Tony Zacaro killing in 1912, cafe business run by Giosue Gallucci's son Luca in 1915, site of fatal shootings of Giosue and Luca Gallucci in 1915.

F - 312 East 108th Street: Childhood home of Joseph Valachi.

Within a few days of Spinelli's death, police arrested Luigi Lazzazaro, 58, of 337 East 108th Street. Lazzazaro was a business partner of the victim, and Nellie Lener said she saw him standing outside the stable's entrance while other men murdered Spinelli inside.

It was said that Lazzazaro conpicuously prevented people from entering the stable just before the gunshots were heard. Rumors circulated that he set up the killing to resolve a dispute over the proceeds from the Harlem horse stealing racket. Lazzazaro was charged with acting in concert with the killers, though he denied knowing anything about the murder. [31]

Giovanni Ravvo was held for a time as a material witness, though he assured the police he had not seen the killers. [32]

Prisco was not arrested for Spinelli's murder until June. [33] However, witnesses were so thoroughly intimidated by the gangster that no convincing case could be made against him. All suspects in the Spinelli murder were released. [34] It seemed that everyone knew who was responsible for the murder of Pasquarella Spinelli, but the case remained officially unsolved.

Newspapers reported that Nellie, fearing for her life after openly accusing Lazzazaro and Prisco, went to join relatives in Italy. Reports indicated that, even across the Atlantic, Nellie was not safe. It was rumored that she soon died under suspicious circumstances.

The Lener genealogist disputed the reports and stated that Nicolina "Nellie" Lener returned to New York in October 1912, after just a few months in Italy, married a non-Italian the following year and died of natural causes several decades later in Queens, New York. [35]

Prisco

Aniello Prisco did not live very long after Spinelli's murder. During a December 15, 1912, attempt to extort money from Giosue Gallucci, an East Harlem entrepreneur with strong underworld and political connections (and rumored links to the stable), Prisco was fatally shot through the head by a Gallucci aide. [36]

Additional killings over the years helped build the Murder Stable's violent reputation. Lazzazaro, who became the facility's sole owner after Spinelli's death, was fatally stabbed near the stable early in 1914. Police arrested Angelo Lasco, an East 108th Street saloonkeeper, for the killing. Authorities believed Lasco killed Lazzazaro in revenge for the Spinelli murder. The fact that Lasco and Spinelli were both originally from Marcianise, Italy, supports that view. [37]

Sicilian Mafia boss Fortunato "Charles" LoMonte reportedly took charge of the building and operated his feed business from the location. He was shot to death near the stable in spring of 1914. [38] Giosue Gallucci and his son Luca were fatally shot a block from the stable in May of 1915. [39] Mafia-linked East Harlem businessman Ippolito Greco, who became the stable's owner sometime after LoMonte's killing, was shot to death as he left the building for home in November of 1915. [40]

The legend of the Murder Stable continued to grow. As late as 1921, after the structure had been demolished, it continued to be mentioned in connection with underworld murders. The New York Tribune's report on the downtown Manhattan killing of Joseph "Joe Pep" Viserti noted that Viserti had lived at Pasquarella Spinelli's old address, across the street from the stable. [41]

Early reports inflated the number of stable-related murders to twenty or more, counting the killings of all those connected in any conceivable way with the establishment. Later on, writers insisted that all of those deaths and others occurred within the confines of the stable itself. Some stated that the remains of murder victims were secretly stashed inside the building.

The stable became linked in tales to members of the Morello-Terranova Mafia clan (who may have had some connection to it), as well as to Ignazio "the Wolf" Lupo. While embellishing its history, writers assigned new addresses for the building, moving it up and down in East Harlem to suit their stories, and dramatically inflated the number of murder victims associated with it.

In their 1940 book Gang Rule in New York, authors Craig Thompson and Allen Raymond properly placed the legendary Murder stable on East 108th Street. But they claimed the building was owned by Ciro Terranova, half-brother of early Mafia boss of bosses Giuseppe Morello.

The Thompson-Raymond story stated that twenty-three men were killed on the site from 1900 to 1917. [42] At the time Gang Rule was written, Ciro "the Artichoke King" Terranova was an underworld figure well remembered in East Harlem. The authors failed to consider that he was just twelve years old in 1900. [43] He may have been a young member of a street gang operating at the site, but he was certainly not the owner of the property.

Bill Brennan, author of 1962's The Frank Costello Story, repeated the East 108th Street location as well as Terranova's ownership. Brennan inflated the Murder Stable body count from twenty-three to thirty. [44]

The stable was moved just one block north in Giuseppe Selvaggi's The Rise of the Mafia in New York. Attributing the information to a source referred to by the alias Zio Trestelle ("Uncle Threestars"), Selvaggi put the structure on the north side of East 108th Street with a second entrance on East 109th Street. [45]

Herbert Asbury, whose The Gangs of New York was published in 1927, a dozen years before the Thompson-Allen book, insisted that the Murder Stable was about a mile farther north. He wrote that the structure was on East 125th Street, which was an out-of-the-way location for the time. [46] Sid Feder and Joachim Joesten jumped on that bandwagon for The Luciano Story, published in 1954, and insisted that East 125th was the right spot. They decided that the stable was a headquarters for Ignazio Lupo and Giuseppe Morello. [47]

While Asbury refused to put a specific number on the killings at the Murder Stable location, he noted that it ranked second only to the "Bloody Angle" of Chinatown in terms of blood spilled. Asbury claimed that Lupo-linked gangsters had been credited with sixty murders in all. [48]

Asbury's mention of sixty killings apparently inspired David Leon Chandler (Brothers in Blood - 1975) and Carl Sifakis (The Mafia Encyclopedia - 1987). Both authors announced that sixty corpses were found at the site of the Murder Stable! Both authors gave sole ownership of the place to Lupo. However, they did move the stable closer to its original East Harlem neighborhood, placing it at 323 East 107th Street (just a few doors too far to the east).

Those authors insisted that the hidden three-score bodies (that never actually existed) were found by authorities tearing the stable down. Chandler stated that the U.S. Secret Service performed the dismantling of the structure, but didn't bother to explain what that federal agency's interest could have been. Sifakis decided to put the date of the stable demolition in 1901 (typo?), which was actually before the killings associated with it had occurred. [49]

Asbury, who unknowingly contributed to the vast escalation of the Murder Stable victim total, offered another tidbit to describe the brutality of Mafia chief Giuseppe Morello. Morello, the author wrote, tortured and murdered his own stepson when he was suspected of betraying Mafia secrets. [50] Feder and Joesten, who blindly accepted the Asbury address for the stable, also repeated the baseless tale of Morello's stepson. [51]

For more on this subject, see "The Murder Stables" by Jon Black on the Gangrule website.

My thanks to Michele Lener.

1 Pasqua Musoni Lener Certificate of Death, Department of Health of the City of New York, no. 9128, corrected copy filed March 3, 1915.

2 New York City Insurance Maps, 1896, 1902, 1911, New York Public Library.

3 Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of 'Little Italy's' King," Fort Wayne IN Journal-Gazette, Dec. 12, 1915, p. 33, and Pittsburgh Press, Dec. 12, 1915, Sunday Magazine p. 4; "Harlem's 'Murder Stable feud' counts 21st victim," New York Herald, Jan. 7, 1917, Sunday Magazine p. 2; New York City Insurance Maps.

4 New York City Insurance Maps; Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of 'Little Italy's' king."

5 Public School No. 172 later became the DeWitt Clinton High School Annex. After that, it was Benjamin Franklin High School. More recently, it was repurposed as the Magnolia Mansion condominium complex.

6 "Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2; "Woman dies in feud begun by daughter," New York Times, March 21, 1912, p. 1.

7 Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of 'Little Italy's' king."

8 "Blackmailer killed as he made threat," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 4; "35 are caught in Black Hand bomb round-up," New York Evening Telegram, July 26, 1913, p. 3; "'Zopo the Terror' dies as he draws weapon to kill," New York Evening World, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 6.

9 Passenger manifest of S.S. La Gascogne, departed Havre on June 24, 1905, arrived New York on July 2, 1905; Aniello Prisco Certificate of Death, registered no. 35154, Department of Health of the City of New York, date of death Dec. 15, 1912; "Prisco, lame gunman, meets death at last," New York Sun, Dec. 17, 1912, p. 16; "'Zopo the Terror' dies as he draws weapon to kill," New York Evening World, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 6. The Sun stated that Pandolfi shot Prisco because Prisco was paying too much attention to Pandolfi's woman friend.

10 "Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2; "'Zopo the Terror' dies as he draws weapon to kill," New York Evening World, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 6; "Cycle of murders," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 3; "Patriotism, pacifism, anarchism, meet here," New York Times, Jan. 6, 1918, p. 54; "Prisco, lame gunman, meets death at last," New York Sun, Dec. 17, 1912, p. 16.. The Evening World and the Sun reported that Monaco and Lener were married.

11 Frank Monaco Certificate of Death, registered no. 32570, Department of Health of the City of New York, date of death Oct. 29, 1911.

12 "Kills man who deceived her," New York Sun, Oct. 30, 1911, p. 2; Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2.

13 Frank Monaco Certificate of Death.

14 "Rich woman slain in Little Italy feud," New York Sun, March 21, 1912, p. 3; "Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2.

15 "Woman dies in feud begun by daughter," New York Times, March 21, 1912, p. 1.

16 "Woman dies in feud begun by daughter," New York Times, March 21, 1912, p. 1; "Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2. According to the Tribune, an autopsy revealed a third bullet wound, in Spinelli's upper left chest.

17 Pasqua Musoni Lener Certificate of Death; Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018. Pasqua Musone was born to Tommaso and Concetta Gionti Musone in Marcianise, Province of Caserta, Region of Campania, Italy. Marcianise sits just south of the City of Caserta, about 12 miles north of Naples.

18 "Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2.

19 Selvaggi, Giuseppe, translated by William A. Packer, The Rise of the Mafia in New York: From 1896 through World War II, New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1978, p. 25-26. Negative portrayals of wealthy women (such as referring to Henrietta Green as a "witch") suggest a pronounced gender bias in this period.

20 Pasqua Musoni Lener Certificate of Death.

21 Passenger manifest of S.S. Hindoustan, departed Naples, arrived New York City on July 6, 1892.

22 New York State Census of 1905, Manhattan borough, Election District 5, Assembly District 33.

23 United States Census of 1910, New York State, New York County, Ward 12, Enumeration District 339. (Sadly, these relationships prevented Nicolina from being known as "Nellie Spinelli.)"

24 Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018.

25 Pedigree Resource Files, Family Search, familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:2:SP35-FM1, May 10, 2011, and familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:2:33XW-6YW, Dec. 28, 2013, accessed May 18, 2018; New York City Marriage Records, 1829-1940, Family Search, familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24ST-GX1, Feb. 10, 2018, accessed May 18, 2018.

26 Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018.

27 Passenger manifest of S.S. Hindoustan, departed Naples, arrived New York City on July 6, 1892; Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018.

28 Passenger manifest of S.S. Entella, departed Naples, arrived New York City on April 7, 1893; Trow's General Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx, City of New York, Vol. CXXIV, for the Year Ending August 1, 1911, New York: Trow Directory, Printing and Bookbinding Company, 1910, p. 854; Tommaso Lener naturalization petition, Supreme Court of New York County, Bundle 299, Record 74, index L 560, March 26, 1906.

29 "Woman dies in feud begun by daughter," New York Times, March 21, 1912, p. 1; "Rich woman slain in Little Italy feud," New York Sun, March 21, 1912, p. 3; Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018. While the Times reported the civil marriage of Lener and Napolitano, the Sun stated that a marriage license was acquired for the couple but no ceremony took place.

30 Valachi, Joseph, The Real Thing: Second Government - The Expose and Inside Doings of Cosa Nostra, unpublished manuscript, Joseph Valachi Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, digitized version on mafiahistory.us. Valachi referred to the Murder Stable and Spinelli on Page 6f1, Page 8, Page 10, Page 11.

31 "Arrest victim's partner," New York Sun, March 23, 1912, p. 1; "Held as woman's slayer," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 24, 1912, p. 58; "Stabbed to death in revenge plot," New York Tribune, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 1.

32 "Murdered in vendetta," New York Tribune, March 21, 1912, p. 2.

33 "Blackmailer killed as he made threat," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 4.

34 "Blackmailer killed as he made threat," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 4.

35 Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of Little Italy's king;" Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018.

36 Aniello Prisco Certificate of Death, registered no. 35154, Department of Health of the City of New York, date of death Dec. 15, 1912; "Prisco, lame gunman, meets death at last," New York Sun, Dec. 17, 1912, p. 16; "'Zopo the Terror' dies as he draws weapon to kill," New York Evening World, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 6; "Kills a gangster to save his uncle," New York Times, Dec. 17, 1912, p. 12; "'Zopo the Gimp,' king of the Black Hand, slain," New York Tribune, Dec. 17, 1912, p. 16; "Man is found dead with bullet holes in his head," New York Press, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 3; "Blackmailer killed as he made threat," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 4; "Blackhand king shot dead when he demanded $100," Bridgeport CT Evening Farmer, Dec. 16, 1912, p. 3; "Record of deaths in murder stable," Niagara Falls Gazette, April 12, 1916.

37 "Rich liveryman slain with knife; cast into snow," New York Evening World, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 14; "Third murder in feud," New York Times, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 2; "Stabbed to death in revenge plot," New York Tribune, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 1; "Cycle of murders," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 3; "Murderer kills victim while crowd watches," New Castle PA Herald, Feb. 20, 1914, p. 15; "Murders man before crowd," Barre VT Daily Times, Feb. 21, 1914, p. 3; Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of Little Italy's king;" Passenger manifest of S.S. Citta di Milano, departed Naples on Dec. 10, 1902, arrived New York on Dec. 25, 1902; Email from Michele Lener, May 17, 2018. Angelo Lasco arrived in New York as a twenty-one-year-old on Christmas of 1902, heading to his brother Michele Lasco's address, 327 East 104th Street.

38 Gentile, Nick, with Felice Chilante, Vita di Capomafia, Rome: Crescenzi Allendorf, 1993, p. 78; "Passersby shot in duel," New York Sun, May 24, 1914, p. 7; "Knife of slayer stays Mafia secret," New York Tribune, May 24, 1914, p. 1; "Shoots man and woman and makes his escape," New York Evening World, May 23, 1914, p. 2; "Lamonte dies of shot wound," New York Sun, May 25, 1914, p. 5; Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of Little Italy's king."

39 Critchley, David, The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931, New York: Routledge, 2009, p. 111; "Little Italy's 'king' and son both shot down," New York Evening World, May 18, 1915, p. 4; "Two shot down in Harlem feud," New York Tribune, May 18, 1915, p. 1; "Father and son shot," New York Times, May 18, 1915, p. 22; "Bullet kills son; 'Little Italy king' is still alive," New York Herald, May 19, 1915, p. 6; "Police to guard funeral," New York Times, May 24, 1915; Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of Little Italy's king."

40 "$5,000 was raised for Baff killing, gunmen confess," New York Evening World, Feb. 11, 1916, p. 3; "Patriotism, pacifism, anarchism, meet here," New York Times, Jan. 6, 1918, p. 12; Thomas, Rowland, "The rise and fall of Little Italy's king."

41 "'Joe Pep,' ruler of Little Italy in Harlem, slain," New York Tribune, Oct. 14, 1921, p. 1.

42 Thompson, Craig, and Allen Raymond, Gang Rule in New York: The Story of a Lawless Era, New York: Dial Press, 1940, p. 4-5.

43 Ciro Terranova Petition for Naturalization, 78124, Supreme Court of the State of New York, submitted July 25, 1918. Terranova was born on July 20, 1888, in the Sicilian province of Palermo.

44 Brennan, Bill, The Frank Costello Story, Derby CT: Monarch Books, 1962, p. 27, 35.

45 Selvaggi, Giuseppe, translated by William A. Packer, The Rise of the Mafia in New York: From 1896 through World War II, New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1978, p. 23.

46 Asbury, Herbert, The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld, Garden City NY: Garden City Publishing, 1928, p. 267-268.

47 Feder, Sid, and Joachim Joesten, The Luciano Story, New York: Da Capo Press, 1994 (originally published by David McKay Co. in 1954), p. 49.

48 Asbury, Herbert, The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld.

49 Chandler, David Leon, Brothers in Blood: The Rise of the Criminal Brotherhoods, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1975, p. 113; Sifakis, Carl, The Mafia Encyclopedia, New York: Facts on File, 1987.

50 Asbury, Herbert, The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld.

51 Feder, Sid, and Joachim Joesten, The Luciano Story.

52 Photograph was published in the New York Herald. It appears to be the East 107th Street (back) entrance of the stable.